Without a doubt, 2020 was one storm of a year that saw a pandemic ravage global economies and industries. But the scale of decline suffered by remittances to Nigeria in 2020 is perhaps the most glaring visualisation of the extent to which 2020 glitched.

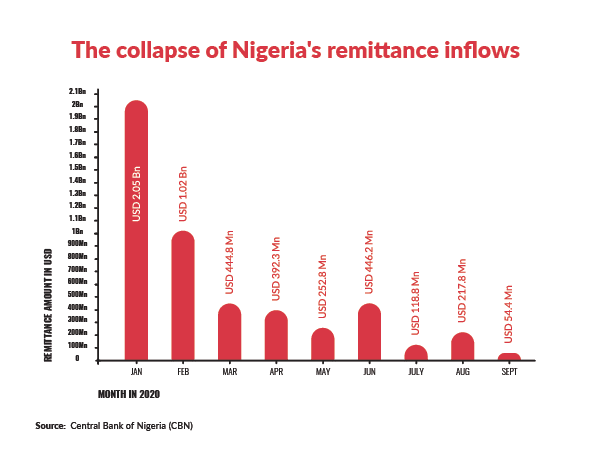

Here’s an unsettling picture: Direct remittances into Nigeria declined by 97.3 percent between January and September 2020.

As gleaned from data recorded by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), the country’s diaspora remittance inflows had shrunk throughout the year in quite the unsettling fashion — from USD 2.05 Bn in January 2020 to USD 54.4 Mn in September.

Every year since 2007, annual remittances to Nigeria (which is simply money sent into the country by Nigerians abroad), has never fallen below USD 17 Bn. Oddly, the available data for the first nine months of 2020 adds up to less than USD 5 Bn.

Unless Nigerians abroad somehow managed to send home the equivalent of the GDP of Equatorial Guinea in the final three months of last year (which is very, very unlikely), then things really slipped to 2004/2005 levels.

This uncharacteristic and unprecedented dip has baffled many and confounded more than a few. It’s been a struggle to make sense of the collapse in remittance inflows to a country that single-handedly accounts for a third of all remittances to sub-Saharan Africa.

Naturally, everyone’s favourite villain, COVID, should get the blame, and of course, it does get a huge chunk of it.

“People have linked it to the pandemic. Nigerian migrants were really affected by economic uncertainties, there were many job losses, and sending money home would have taken the backseat” says Ese Oikhala, a Consulting Associate at SBM Intelligence.

“However, looking at what happened and comparing it to the 2008 financial crisis, it can be seen that certain monetary policy measures put in place this time around also affected things,” she says.

It appears the collective opinion of experts and observers on the local front is that pinning the entirety of a slump of this magnitude on COVID might just be a little too convenient.

Now, here’s a go at answering the question on everyone’s lips or minds: Where did all the money from “the abroad” go?

So what’s the story here?

Once upon a time, oil was Nigeria’s gold, known to be the country’s biggest money plug. And to many, it (oil) is still regarded, sentimentally, as Nigeria’s gold. Only, that black sludge is no longer the cash cow it used to be, and has since been usurped.

So what’s the new cash cow? One would be forgiven to think it’s probably another kind of stuff pulled out from the earth, or maybe some stuff produced out of stuff pulled out from the earth. But it’s none of that.

These days, a major source of cash into Nigeria is actually cold hard cash itself sent in by folks aboard, formally called “remittances.” Nigeria’s remittance inflows first outstripped its oil revenues in 2015, and that’s been the norm since then, as reflected in a PwC analysis.

As of 2014, 17.5 million Nigerians were reported to be living in foreign countries, with the U.K. and the U.S.A having more than 2 million Nigerians each. The Nigerian diaspora is an economically vibrant bunch putting in work all over the world and repatriating funds to families, households, acquaintances, and associates back home.

In 2019, remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) overtook foreign direct investment (FDI) as the largest source of incoming capital. Previously, remittances had outpaced official development assistance (ODA) and private portfolio balance.

It’s quite a big deal too

The importance of remittances is in the role they play in economies. They help poorer recipients meet basic needs, fund cash and non-cash investments, finance education, foster new businesses, service debt, and essentially, drive economic growth.

It sounds like “small money for upkeep” until it registers that diaspora remittances to Nigeria in 2018 was the equivalent of 83 percent of that year’s national budget. That year, the figure hit USD 25 Bn; the GDP of Mali and Equatorial Guinea combined at the time.

Indeed, nearly half of all remittance flows to sub-Saharan Africa end up in Nigeria, though at 6 percent, Nigeria’s remittance flows as a percentage of GDP is relatively low. In South Sudan, contrastingly, that figure is 34 percent.

But 2020 happened. The World Bank sounded the alarm bells as early as April when it predicted the sharpest decline of remittances in recent history. It projected remittances to fall by nearly 20 percent due to the economic crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The projected fall, which would be the sharpest decline in recent history, is largely due to a fall in the wages and employment of migrant workers, who tend to be more vulnerable to loss of employment and wages during an economic crisis in a host country,” reads the statement from the World Bank.

“Remittances to low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are projected to fall by 19.7 percent to USD 445 Bn, representing a loss of a crucial financing lifeline for many vulnerable households.”

But it’s unlikely that the World Bank, even in the worst-case scenario, had envisioned that the top recipient of remittances to sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria, would suffer a downturn that would see inflows drop to levels that belong in the early 2000s.

Following the money

Historically, remittance inflows to LMICs have a way of holding up even during periods of severe economic downturn.

During the crisis of 2008, for example, remittances dipped but largely stayed resilient despite the biting recession. And it’s something of an unofficial consensus that people living and working abroad often go out of their way to support folks back home during such lean times.

So, a dip in remittances due to COVID was expected, alright, but not the sort of decline recorded in Nigeria.

In fact, the countries known to be among the largest remittance recipients globally, such as India, China, Mexico, and the Philippines, all witnessed remittance dips of different magnitudes for much of last year.

However, none suffered a remittance free-fall like Nigeria’s. Some countries even saw their inflows recover from the battering and shoot back up after the early bumps caused by COVID.

For example, remittances to Mexico increased to USD 10.6 Bn in the third quarter of 2020 from USD 9.8 Bn in the second quarter of 2020, according to Banco de México. Similarly, the Reserve Bank of India reports that remittances to India increased to USD 13.9 Bn in the third quarter of 2020 from USD 12.4 Bn in the second quarter of 2020.

Nigeria can’t relate, it was a bloodbath in Africa’s most populous nation. In any case, the identical view of several analysts and observers is that there’s more to the decline than COVID.

Where did all the money from “the abroad” go?

The most common alternative argument (beyond COVID) is that there was some kind of alternative foreign currency swap arrangement at play that took transactions away from the formal channels.

Last year, the first big drop in remittances to Nigeria was recorded in March when the amount fell to USD 444.8 Mn from USD 1.02 Bn in February. From there, things pretty much went downhill. The timing of this plunge also tells a story.

It was in March that the CBN caved and devalued the naira — from NGN 360.00/USD 1.00 to NGN 380.00/USD 1.00 — owing to depleting foreign reserves caused by the collapse of oil prices. But the official rate was far from the rate in the parallel market which was closer to NGN 450.00 to the dollar.

Given that at this time CBN regulations required remittances to be paid out by the banks receiving them in naira at the official rate, it is not unreasonable to think that people would have taken to finding alternative means of transferring funds into the country at closer to the parallel rate.

For them, that would mean more naira for fewer dollars, or better yet, more naira for every dollar. And who doesn’t like more money?

It is believed that one way people circumvented the official channels was through swaps – someone who wants to send dollars to Nigeria would find (often through online channels) someone who wanted to send naira offshore as FX.

The parties would then agree on a rate and the person abroad would send the dollars to a dollar account in the U.S. (for example), while the person in Nigeria would send his naira to the Nigerian account of the person abroad. This bypasses the official system and the dollars do not officially enter Nigeria.

As they say in Nigeria, the money from “the abroad” was coming in, just not through the official channels.

There is also the claim that cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, has become quite popular in such cross-border funds transfer to Nigeria. Some estimates claim that Nigeria is home to the world’s second-largest bitcoin market after the U.S.

There are several crypto platforms that use bitcoin to facilitate faster and cheaper transfers to Nigeria from abroad. Such transactions would occur outside the CBN’s net.

And then there’s another explanation hinged on the possibility of International Money Transfer Organisations (IMTOs) profiting off of foreign exchange rate disparities in Nigeria, thereby reducing dollar inflows.

Either way, some recent policy tweaks by the CBN suggest that at least one of the three explanations above would have significantly impacted remittances. For one, the CBN has called out the practice of certain IMTOs.

The FX scenario

It can’t be ignored that one of the main issues at the centre of Nigeria’s remittance entanglement is the foreign exchange situation in the country.

Nigeria runs a fixed exchange rate propped up by the CBN which is famous or infamous for defending the naira by dipping into its foreign reserves.

However, there is also a black market for FX in Nigeria with rates that are usually higher than the official one. Some would say the rate in the black market is a truer reflection of the real value of the naira, and that the CBN and the government have the naira overvalued.

Generally, when foreign reserves grow thin, as is often the case when oil revenue declines, the CBN finds it increasingly difficult to match the demand for the dollar.

What often follows is the CBN placing specific restrictions on FX access. Thus, the dollar becomes scarce, the naira is put under pressure, and the exchange rate of the naira to the dollar soars in the black market. (An earlier story on WeeTracker explained this issue exhaustively.)

Early last year, the CBN was forced to devalue the local currency to ease the pressure on the nation’s reserves. But the new official rate trailed the rate in the parallel market by some distance. Such a situation creates room for foreign exchange arbitrage.

“Instead of using the formal channels, CBN policy drove people to repatriate their US dollars through the black market and informal remittance channels such as peer-to-peer currency exchanges and crypto,” notes Ebenezer Oyamujo, an Investment Analyst formerly of Planet Capital and Alpha Morgan Capital.

Oikhala of SBM Intel shares similar sentiments. As she says, “Because they [the CBN] were trying to stabilize the naira-dollar exchange rate, they started limiting the flow of FX in the market, and there was a dollar scarcity. People who were sent dollars from abroad couldn’t even access it from the banks, nor did they like the exchange rate of banks which was much lower than the black market.”

According to her, this caused people to begin to consider other alternatives, which were mostly unofficial channels.

It’s a plausible explanation seeing as IMTOs themselves are also known to take advantage of the foreign exchange arbitrage in Nigeria.

In late November, the CBN issued a now-widely-publicised circular that compelled IMTOs to, as from December 4, 2020, only pay diaspora remittances to recipients in foreign currency (US dollars) through banks; as cash for pickup, or into the recipient’s ordinary domiciliary account.

For the longest time, it was an open secret that many IMTOs engaged in arbitrage arrangements on the naira-dollar exchange rate, which the CBN says “resulted in a significant drop in flows into the country.”

How so? Well, before now, IMTOs only needed to find a swap partner; a person or entity from whom they would get the local currency and take their dollars offshore. The dynamics of such an arrangement is such that the physical cash never gets to enter the country.

This arrangement also gave remittance companies a profiteering edge. They are able to make money on their ability to take advantage of the difference between the official exchange rate and the black market rate.

IMTOs do this by finding a swap partner that would exchange their FX at rates lower than official rates.

That’s the arbitrage phenomenon in a nutshell, and it could have contributed to the huge remittance dip recorded in 2020. At least, the CBN does seem to think so.