The Love-Hate Business Relations Between Nigeria & South Africa With MTN In-Between

The ‘South-West’ Connection

Lagos; Nigeria’s commercial nerve and most industrialised city, is home to one of the country’s biggest luxury shopping centres – some imposing, cosy structure known as The Palms Shopping Mall.

A casual stroll through the row of stores that flank either side of maze-like grid created by the seemingly-unending, meandering passageway reveals a certain calmness and serenity that is not exactly the stuff of normal life in the often charged-up atmosphere of the city’s metropolis.

Source: nitestay.com

A visit to The Palms is almost like taking a break from the hustle and bustle that is an ever-present feature of life in the city. Some would even say the aesthetics and layout of the shopping centre might just give one the feeling of being in another country – one that feels a lot like South Africa.

And maybe for good reasons too. Reasons that have more to do with the identity of the dozens of stores in the mall themselves than the striking resemblance of the retail space to the many smart, air-conditioned shopping centres that dot the scenes in Johannesburg.

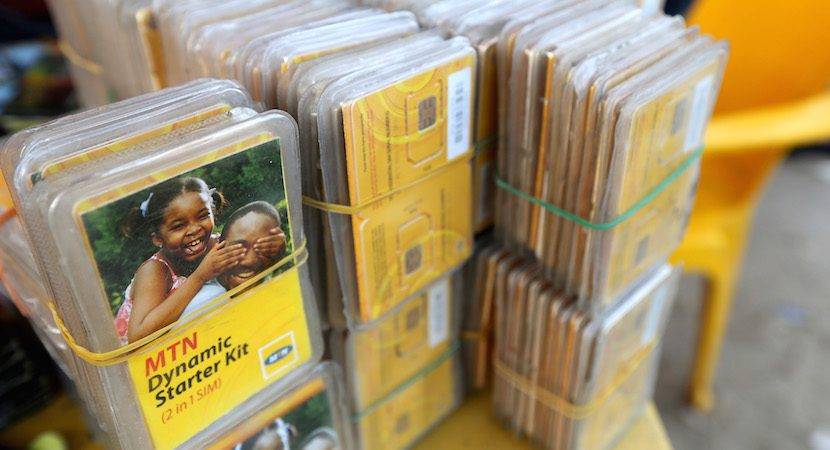

Sitting on one generous portion of space is South African telecoms group, MTN – incidentally the biggest telecoms operator in Nigeria with some 55 million subscribers in almost 4,000 villages, towns, and cities across every state in the country – while also holding 38.4 percent of Nigeria’s telecoms market share and even dwarfing its business in parent country, South Africa, by some distance. And that’s just for starters.

Go further down the bowels of the shopping centre and a hypermarket chain from down South, Shoprite, sits proudly like a peacock in a gathering of pigeons, being the mall’s main tenant.

Source: aboutlagos.com

You will get the idea how big it is when you hear the average Nigerian loosely speak of going to Shoprite when, in actual fact, the plan is to go see Captain Marvel at Silverbird Cinemas (one of the mall’s other occupants). It’s almost as though Shoprite has become the de facto name of the entire mall. And there’s more.

At the very centre of the mall is South Africa’s Massmart Group-owned consumer goods store, Game – another proud occupant of the mall with its intimidating catalogue of quality household appliances, amongst other things, put up for sale at, sometimes, unbelievable prices. And all that is if you even have the time to really explore the mall.

Source: myguidenigeria.com

Even at that, getting only as far as the entrance brings a counter of DStv and GOtv into view – two satellite television services owned by Johannesburg-based TV service provider, Multichoice – who themselves have hundreds of thousands of Nigerians on board as subscribers. A little further down and you’ll find Cape Town-based clothing retailer, Woolworths, perched nicely. Do you see a pattern yet?

There are a few other high-end, chic malls in Lagos but even in the ‘not-so-nice’ ones, it’s more or less a similar situation – some touch of Jozi Land, just like it is with The Palms and its ‘equally affluent cousin,’ Ikeja City Mall.

It’s no fluke or one-off; throughout Nigeria, names like Truworths, Markhams, Mr. Price, Spur, Steers, Mugg & Bean, and Foschini, fill the Nigerian air with a thick cloud of South African smoke.

Away from retail fronts and fast food outlets, there are also some fingerprints that can be traced back to the south in Nigeria’s financial services sector. There’s Stanbic IBTC Bank – a member of South Africa’s Standard Bank Group – pulling its weight in the sector. And guess who financed the USD 100 Mn Ikeji City Mall. You got that right – the same bank!

The few paragraphs above encapsulate, to some degree, the extent of South African presence on the Nigerian business landscape. In the past two decades, efforts geared towards expanding into Nigeria by various South African companies have been nothing short of aggressive.

One might even begin to think both countries are some sort of geographical

neighbours given the tendency of the guys from the south to turn their attention westwards once they’ve gained some sort of foothold back home.

Well, this is understandable given the reputation of the West African nation as the Giant of Africa – a reputation built on the backs of the country’s sheer size and population of over 190 million – unarguably serving up a market size that comfortably trumps all others on the continent. Granted, the market in South Africa is matured but in Nigeria, they seem to have found their unsullied, untamed bride.

More so, Nigeria is considered Africa’s largest economy – as a matter of fact, beating South Africa into second place – and with the country’s recent economic resurgence, together with the relatively few powerful local companies offering any form of competition, it does seem like ample opportunities abound. One that the firms from SA are keen to jump at.

Bad Blood Brewing?

Actually, for all of Nigeria’s promise of treasures hidden just beneath the surface, it is hardly the easiest terrain to take the digger to. But despite the obvious infrastructural and bureaucratic shortcomings, large South African companies that have opted to risk the treacherous terrain, appear to have landed the gold.

Take South African telecoms giant, MTN, for instance. Having struggled to keep up with the stiff competition offered by the likes of Vodacom, Cell C and Telkom Mobile back home, it was always going to be just a matter of time before its business in Nigeria overtook that in SA – in this case, taking only a few years.

Even though MTN launched in Nigeria several years after making a play in South Africa’s telecom sector, MTN Nigeria’s profits currently almost

doubles the numbers coming from down south.

Then, there’s Multichoice which appears to be doing well in what is not the easiest of markets and hypermarket chain, Shoprite, which has become something of a household name throughout Nigeria – with several stores already opened across the country and plans to spring up more.

Of course, all these hits are interspersed with a few misses here and there but the general feeling is that the Nigerian market has been, more or less, a fertile ground for large South African corporates. And there are sections of the locals that are indifferent to this fact, as there are those who are irked by it.

Moreover, for every Nigerian who is pleased with the quality of service at Spur and the variety and convenience afforded at Game, there’s another who is livid with the prices at Woolworths (I’m actually one of those). Compared to the price tags on its products back in SA, it seems a lot like a rip-off. And that’s even putting it nicely.

Away from the business end of things, for the layman, both countries have been locked in some kind of unspoken battle for supremacy for as long as memory can recall. Some might want to downplay it as ‘sibling rivalry,’ but there may be some bad blood brewing there.

To the average South African, the archetypal Nigerian is boisterous, arrogant, over-confident, and maybe bearing a tinge of hubris. Whenever there’s talk of an email scam, a drug bust, or a compromised prostitution ring or crime syndicate, the first impulse is to blame it on the Nigerians living in SA. Evidence is secondary.

In essence, the stereotype borders around South Africans blaming Nigerians in their country for anything that reeks of organised crime, even though it seems they’re totally crazy about Nigerian celebrities and pastors, and perhaps wish they could muster half the swagger and attention-grabbing manner.

And then, there’s that one incident which took place in Lagos, Nigeria, four years back in which a church building collapsed, claiming some 115 lives, 84 of which were South African. It doesn’t help that the aftermath of the tragedy was laden with complaints from officials in Pretoria who were calling out the Nigerian authorities for being lackadaisical about repatriating the bodies of the deceased.

Source: echurchafrica.com

It’s a milder view from Nigeria who view their Southern counterparts as aggrieved siblings who are just upset because they don’t get to hog the spotlight like their other haughty, spoilt sibling.

Nigerians have made no secret of their fondness for SA as a prime holiday destination – as close to the western world as one can get when all else fails – and they consider it painful watching the country struggle in ways that were previously only associated with other African countries – though, there’s a bit of epicaricacy accompanying the concern.

Many Nigerians are of the opinion that South Africans would have done without Nigeria on map, leaving them as the undisputed candidate for the title of Africa’s one and only beautiful bride. With Nigeria seemingly undeservingly finding its way into the limelight all the time, it’s hard to stomach not getting as much attention as they well and truly deserve.

But as would any wise co-wife in a polygamous setting who is quick to recognise that there’s enough living space for everyone, Nigerians know the best move is to learn to co-exist.

Back To The Business Front

There’s a feeling amongst Africans, not just Nigerians, that South Africa seems to throw its weight about, especially in issues related to business on the continent.

The angst is founded on the narrative that SA business people/companies come across as “arrogant” and “culturally-insensitive” – having a mercantile and predatory mindset that only concerns itself with grabbing all that is available irrespective of whose ox is gored in the process.

With regards to Nigeria-South Africa bilateral relations, even though trade between both countries went north of USD 3.6 Bn in 2011, the story has been mainly one of diplomatic spats, bureaucratic bickerings, and immigration squabbles.

Apart from the xenophobic attacks which have tainted South Africa’s post-apartheid years, (and which cannot be expressly labeled as being wholly targeted at Nigerians living in South Africa since it has also affected people from other African countries), we can trace the animosity to as far back as 2012 when some Nigerians were repatriated upon arriving at the international airport in Johannesburg for allegedly bearing fake Yellow Fever Vaccine Certificates.

As expected, the Nigerian reprisal came in like manner – dozens of South Africans sent back home upon arriving the international wing of the Murtala Mohammed Airport in Lagos. The tit-for-tat, diplomatic spat that followed was as entertaining as it was disheartening.

Since then, uneasy calm is as good a cordial relationship as one can get between both countries, and that’s only when they’re not at loggerheads, which actually happens more often than not with some entities bearing the brunt more than others – businesses, unfortunately, serving as the shuttlecock that is slapped around in this game of “bureaucratic badminton.”

With a number of South African companies finding a second home in Nigeria, it’s almost appropriate to assert that some of them have been caught in the crossfire in what looks like a periodic face-off between two governments. None more so than telecoms company, MTN.

For every harm done to a small Nigerian business in what looks like a xenophobic attack or for every diplomat refused entry into SA, there are hundreds of Nigerians threatening fire and brimstone on big South African firms in Nigeria.

Well, that has never really amounted to anything and the hope is that it’ll stay that way. Perhaps that’s because in this pissing contest, some persons in Nigeria may have figured how to go for the jugular without actually drawing blood, and MTN happens to be playing the unenviable role of whipping boy.

The Love-Hate Relationship Between MTN And Nigeria

Simply put; telecoms giant, MTN, are the biggest company from down south in Nigeria and the biggest telecoms operator in the country too – maybe that’s why the company makes such a prime target, and that’s if the rumours of an ongoing witch hunt are true.

MTN’s journey in Nigeria has more or less entered the country’s business folklore – one that is often quoted by country officials to inform investors of the perils of taking a pass on Nigeria’s robust market.

As the story goes, it was around the year 2001 when the Nigerian government offered the country’s nascent telecoms sector to British telecoms operator, Vodafone, on a platter. Having weighed the enormous risk, the Brits considered the offer a non-starter and opted to take a pass.

Then came younger, smaller rival from SA, MTN, which along a few other operators decided to risk it on the country – paying USD 285 Mn for a license and risking an additional USD 400 Mn in initial investments (putting a lot faith in a country that was barely recovering from economic sanctions and external debt triggered by military rule that only ended in 1999).

If that was a gamble, it’s one that has more than hit the jackpot. Where other licensees managed slow rollouts and multiple ownership changes, MTN remained rock solid and consolidated its position by expanding aggressively, covering the length and breadth of Nigeria and scribbling its name in first position on the leaderboard since that first call was made on its network in May 2001.

One look at its current numbers in Nigeria and you get the idea that the investment has paid off in spectacular fashion. We’re talking about 55 million subscribers throughout Nigeria – no one else comes close.

With basically no infrastructure as of 2001, the Nigerian telecoms industry has been transformed into a

More so, MTN claims to have made further investments of around USD 13 Bn in the country and paid out no less than USD 5.5 Bn in taxes to the Nigerian government to date. The impact on the Nigerian economy has been immense. Jobs created by the company across the telecoms value chain have been aplenty.

At face value, it looks like MTN has been more than anything else, a loyal adopted son, and one can’t help but wonder how things went south – no pun intended.

How Did The Journey Go Sour?

Once MTN got its operating license from the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), the company wasted no time asserting itself as a dominant force.

At the time of rolling out its services, MTN claimed per second billing was impossible for subscribers, despite evidence to the contrary in other climes, including South Africa, its birthplace.

Not even several admonitions by the NCC could get MTN to budge from its position on the matter and even now, there are Nigerians who are still irked by the fact that, for three years, MTN made a killing from excess costs charged in per minute calls to millions of subscribers.

It was actually the coming of Nigeria’s premier indigenous telecoms brand, Globacom, in 2003, which offered cheaper call rates per second, together with ECONET (now Airtel Nigeria) which soon followed in the footsteps of Globacom, that forced MTN’s hand.

Probably in an effort to save its depleting subscriber base, it introduced the same per second billing which it initially described as “technologically impossible.”

Some would say the company could have implemented the cheaper rates all along but was wont to because of the funds it was raking in. In any case, it still remained a darling. The billing saga was just a molehill compared to the mountain that was to come.

In 2014, the company was fined, alongside other network providers, for poor service. Later that year, MTN was calling out the Nigerian government for excessive tax claims. It was just a clash of wills, no shots fired. But things soon got messy.

Around when the Muhammadu Buhari-led administration took office for his first tenure in 2015, something changed and MTN found itself falling from the government’s good graces. From model corporate citizen, it was now facing stiff sanctions as though it were a rogue institution.

For faltering on a government directive which demanded that all unregistered lines be disconnected after a specific deadline, MTN was slapped with a USD 5.2 Bn fine for failing to cut off just over five million lines that were not registered by their users during the exercise.

Image Credits: George Osodi/Bloomberg

It was an enormous fine – 37 percent of the company’s revenue, more than twice its annual profits, an amount that could bankrupt the company from Nigeria to SA – and it got tongues wagging within the industry.

The regulator was out for blood and insisted that the fine be paid in full but after several proceedings – which unseated the company’s CEO at the time and got a former US Attorney General drawn into the matter as negotiator – the fine dropped to USD 1.7 Bn.

As part of concessions made during the negotiations, it is understood that MTN agreed to demonstrate some goodwill by listing its shares on the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE), just as it had done in the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE).

It is pretty much public knowledge that neither the reduced fine nor the IPO listing has since materialised. Sources say only a part of the fine has been paid and plans to go public in Nigeria were halted when the company was hit with yet another hefty fine last year.

In May 2017, shortly after that year’s Workers’ Day celebrations, the company came under fire after it reportedly laid off 15 percent of its Nigerian workforce, allegedly declaring the now vacant positions available on a contract basis.

Claims from aggrieved parties had it that the retrenchment exercise mostly affected workers who had put in at least five years on the job and suits were threatened. But it all came to nothing. Actually, MTN does have the right to downsize as it deems fit.

More vitriol came in July 2018 when the company’s offices across major Nigerian cities were picketed by members of the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC) who were reportedly protesting the “non-unionisation of its workers.”

August 2018 brought news of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) delivering a letter to MTN wherein it demanded that the telecoms operator return USD 8.1 Bn that had been “illegally repatriated” out of the country between 2007 and 2015.

The dispute stemmed from some grey areas and misinterpretations around something called the Certificate of Capital Importation (CCI) issued to bringers of foreign investment into Nigeria in relation to the company’s shareholding. And according to the CBN, MTN had overplayed its hand by flouting the fundamental rules of engagement.

As it stands, maybe the CBN are justified in their claims that the telecoms operator has indeed stepped out of line, but the guys from the South can hardly be blamed given Nigeria’s all too recondite and somewhat abstruse foreign exchange laws – something that is often an albatross.

Nobody expected what was to come next, though. Still reeling from the shock of the CBN’s claims, MTN was again rocked by a USD 2 Bn tax bill relating to VAT and import duties in September 2018 by Nigeria’s chief lawyer who, for some reason, appeared to have no trouble juggling his actual office with the role of tax chief. Isn’t that some motivation?

MTN have since responded by imploring the Federal High Court to dismiss the government’s claims in an effort that seems more like buying time than tackling the government head-on. The whole thing might drag on for a while but at this point, it’s hard to resist the urge to state that some persons might be trying to alienate the company and maybe push it out of the country.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The row between South Africa’s MTN and the Nigerian government is symptomatic of the fractious trade relations between both countries in which one country could be described as unwilling to offer similar opportunities for the other to thrive, and the other is choosing to retaliate by stifling the thriving businesses of its counterpart within its shores.

Truth be told, for all the talk of South African multinationals being out to milk other countries dry, there are also some undeniable, very positive aspects of their invasion.

Yes, such companies have shipped hundreds of expatriates into the host countries but the jobs created for the locals and all-round development triggered have been tremendous. They also take some of the credit for the innovation that has flooded such sectors as banking and telecoms in recent times.

In terms of overall trade, between 2007 and 2016, South Africa maintained a trade deficit with Nigeria, something that is heavily linked to the its large imports of crude oil which have consistently accounted for up to 99 percent of South Africa’s imports from Nigeria.

There’s more diversification on the exports front. In 2016, South Africa exported goods worth over USD 438 Mn compared over USD 2 Bn in imports from Nigeria. However, when considering the African market, Nigeria ranks 12th as an export destination for South Africa’s goods, whilst also ranking 1st as most important import source from Africa.

In terms of GDP, both countries occupy the top two positions with Nigeria at USD 376.2 Bn and South Africa at USD 349.2 Bn. If these numbers mean anything, it’s the fact that putting bilateral trade relations between both countries in jeopardy will do more harm than good to either side.

There’s a theory that the hostility on the Nigerian front is borne out of deep-seated dissatisfaction than any kind of astuteness or shrewdness.

Even though Nigerians are known to run businesses and hold jobs in other countries (SA inclusive), none of the success achieved outside the country has been of the scale of, for instance, South African companies like MTN, which is known to turn in most of its profits from abroad.

There have been attempts by Nigerian companies to expand across the continent but none have come close to the success South African companies seem to enjoy with ease when they do the same.

Even the continent-wide expansion efforts of Aliko Dangote – Africa’s richest man who also happens to be Nigerian – has yielded mixed results. To date, his cement business which has taken root in other parts of Africa still sees the bulk of its profit trickle in from Nigeria.

In the same vein, defending the rights of a successful Nigerian business which bosses the scene abroad and turns in huge profits back home isn’t exactly one of the strong suits of the Nigerian government.

Apart from the country’s diaspora which is known to wire billions of dollars back home annually, there is still some way to go in the task of setting up a Multichoice or a Shoprite that will go elsewhere and hold its own.

And that’s probably why it appears the Nigerian government is playing that one card where the country’s stupendous population is talked up as a market that must be “protected,” lest be overtaken by “avaricious

Or, perhaps this a zero-sum scenario where every penny earned by any non-Nigerian firm from the country in the name of business and investment is described as “taking advantage of Nigerians.” How comical.

We would like to hope not. And also hope that this is not a case of attempting to clip the wings of the

In any case, there’s no doubt that there’s been hostilities and shortcomings from either side and even when it does seem like there’s an understanding, it’s only a matter of time before the next big squabble. But going forward, maybe either side will be better served by burying the hatchet and forging ahead together.

On the Nigerian front, it’s bad optics to lay down the gauntlet against already-existing foreign investors who may have well siphoned a lot through the backdoor, but have also given back just as much or maybe even more.

The West African nation isn’t exactly one of the easiest places to do business and if I were an investor looking for an opportunity, I’d most likely be forced into a rethink in light of the hostile treatment of a company many consider the poster child for foreign investment in Nigeria; a country that is, in fact, still patching itself up from the economic recession of 2016, and could use all the foreign investment it can lay hands on.

For South Africa, if the track record of their businesses in and with Nigeria is anything to go by, then it is clear that a market like Nigeria’s is not one to be toyed with or passed

Much like SA, Nigeria remains a powerhouse that cannot be ignored – more like a strong business ally – and perhaps the Cyril Ramaphosa-led administration might want to cede some territory too when the time comes as a show of good faith.

These are two very powerful African nations – if diplomacy fails and bilateral ties are severed, well you know what they say about when two elephants do battle.