The Cost Of Kenya’s “Mitumba Ban” Is USD 159 Mn And 700,000 Lost Jobs

Counting the cost of the mitumba ban

With 25 outlets and up to 300 employees on its payroll, Think Twice Second-Hand Clothes shops (or “T2” as regulars call it) is a popular spot for second-hand clothes (also known as “mitumba”) in Kenya.

Although not nearly as popular as the bubbly Gikomba market in Nairobi which is the turf of some 65,000 mitumba traders, T2 does have a reputation as a wholesaler and retailer of second-hand clothes, shoes, carpets, mats, bags, toys, and home textiles like curtains and beddings — all on the cheap and of decent quality too.

But come the next few days, T2 will likely be no more. According to the company, the closure of all of its branches and the laying off of all of its employees is imminent. The reason? A pronouncement from the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS) dated 31 March 2020.

A little over two months ago, the KEBS issued a ban on the importation of second-hand clothes and shoes based on the presumption that those imported second-hand items are a COVID-19 risk. It was a precautionary move.

Although there is currently no scientific evidence that the coronavirus can survive in second-hand clothes (or any other type of goods) imported from anywhere in the world, KEBS opted to take no chances.

Despite calls from interest groups urging a reversal — including one from an organisation which argued that the decision was made “under the false pretenses that the virus can be transmitted through used footwear and textiles” — the ban remains in place indefinitely.

The result? Numerous businesses going under and a staggering number of people staring down the barrel having seen their source of livelihood get yanked away.

How much of a big deal is the mitumba business?

T2 released a communique stating that, with immediate effect, all of its 25 outlets in Kenya are shutting down, and the company’s over 300 employees are to be laid off.

The company said it has been forced to go down that road because of the ban. It also warned that the approximately 700,000 Kenyans who make a living directly from trading second-hand clothes and shoes are being deprived of their livelihood.

Furthermore, T2 stated in its impassioned message that the ban was effectively a slap on the face of 80 percent of Kenya’s population which it claims are repeat buyers of second-hand wears. If those numbers are anywhere near accurate, then someone should probably be listening.

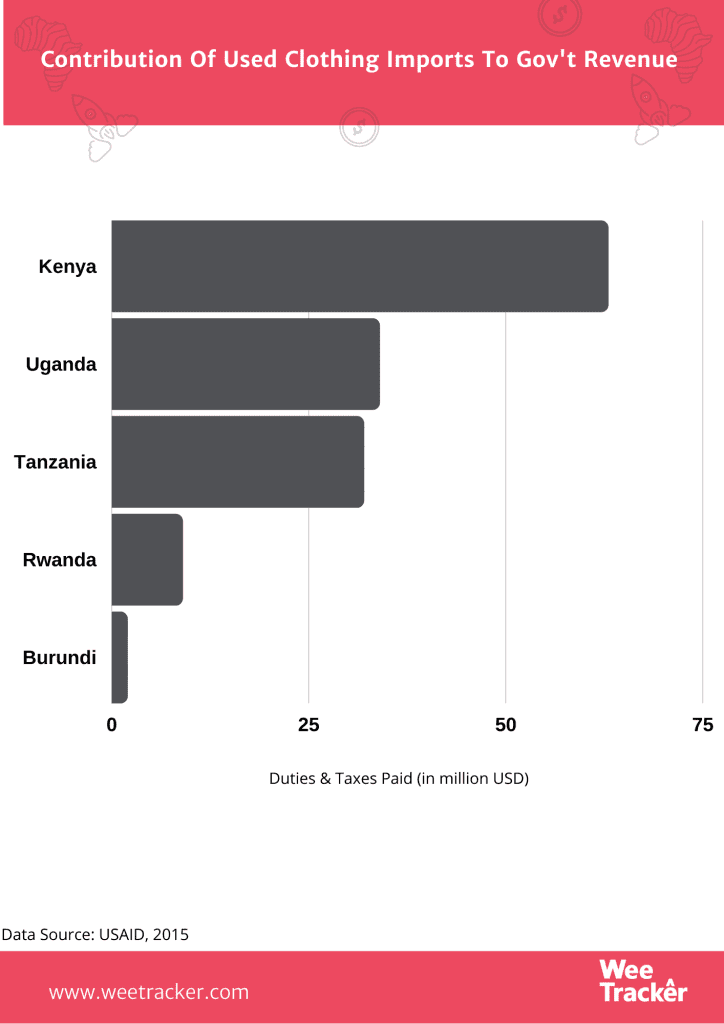

Alongside other African countries like Ghana, Tanzania, Benin, and Uganda, Kenya is among the world’s biggest market for second-hand clothes. In fact, by itself, East Africa imports over USD 150 Mn worth of used clothes and shoes, largely from the US and Europe.

In 2017, USAID estimated that the industry employed 355,000 people and generated USD 230 Mn in government revenue. An additional 1.4 million people in the East Africa Community bloc are estimated to be directly or indirectly making a living from the trade of second-hand clothes and shoes.

Inside Kenya’s mitumba business

Second-hand clothes typically come from the United States and Europe where they are discarded as worthless at charity shops or thrift stores and then shipped thousands of miles to another continent.

Kenya’s used clothing and footwear are mainly imported from the US, the UK, and China — all COVID-19 hotspots in their own right. Kenya is the biggest market for second-hand clothing in East Africa. One can buy used wears for as low as KES 10.00 (USD 0.094) and a small mitumba business can be funded with as little as KES 1 K (USD 9.40).

According to a 2014 report by Reuters, charity or thrift shops in the West sift donated items, often keeping just a quarter of the items. The rest are sold to exporters for up to 90 U.S. cents per kilogram, then wrapped in 45kg bales and packed in containers – a standard 40-foot container holds about 550 bales, equivalent to about 25 tonnes of clothes.

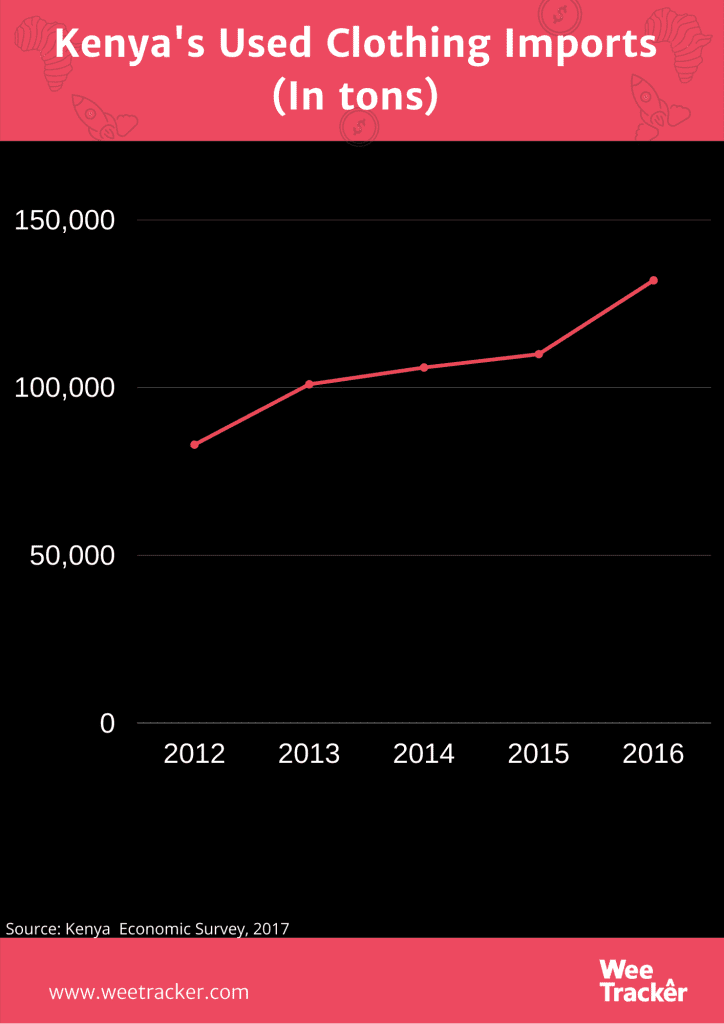

Such containers end up in ships sailing to countries like Kenya where they find a vibrant market. Data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) says Kenya imported 177,160 tonnes of mitumba in 2019, valued at about KES 17 Bn (USD 159.8 Mn), and Kenyans spent KES 11.96 Bn (USD 112.4 Mn) in the first six months of 2019 on second-hand wears.

Apart from Kenya’s largest mitumba trading area, Gikomba market, there are a dozen or so other smaller mitumba markets in Nairobi and similar markets around the country.

Due to its informal nature, it is difficult to pin down precise numbers but there are indications that the mitumba business employs hundreds of thousands of Kenyans.

The business also proves a decent source of revenue for the Kenyan government. As of 2014, customs agents at Kenya’s Mombasa port reportedly raked in duties of KES 1.2 Mn (USD 11.2 K) or more per container.

At the market, Nairobi City County profits by charging a fee of KES 50.00 (USD 0.47) each day from informal hawkers. Bigger shacks or shops pay between KES 4 K (USD 37.61) to KES 15 K (USD 141.03) a year. Gikomba market has over 10,000 stalls.

The state statistics agency said imports amounted to 100,000 tonnes worth about USD 90 Mn in 2013 alone. According to a Reuters estimate, at least 4,000 containers laden with second-hand clothes and shoes arrive in Kenya every year and the potential duties amount to KES 4.8 Bn (USD 45 Mn at current rates) annually.

Between COVID-19 and second-hand wears

The Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles Association (SMART) recently urged the Kenyan government to reverse its recent COVID-19-enforced ban on the import of used garments and shoes, stating that all available research on the novel coronavirus shows they do not pose a threat to people who wear such garments or footwear.

Kenya has now registered over 2,000 COVID-19 infections since the outbreak of the pandemic. As of March 31 when KEBS placed a temporary ban on the importation of used wears as a precaution, there were only 59 cases. Is the bureau’s call justified? Well, the mitumba traders’ answer is “no” for sure.

In imploring the authorities to overturn the ban, the SMART made a decent argument.

Although numerous studies including those published in the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet have shown that COVID-19 may be detectable on hard, non-porous surfaces like plastics and metals for hours and potentially up to 2-3 days, they also say the virus is even less likely to survive on soft, porous surfaces like textiles including rugs, carpets, shoes, and clothing, whether they might be new or used, the SMART emphasized.

Further, the group argued that guidelines issued by the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), state that one can easily eliminate whatever small risk might be present on soft, porous surfaces like clothes by laundering the textile according to manufacturer instructions in warm water.

Besides citing examples in frontline medical personnel and hospitals reusing PPEs and medical work clothes after treatment, it noted that used clothing shipped overseas “is typically in transit for weeks, if not months at a time–far longer than the virus has ever been shown to survive on even the most hospitable non-porous hard surfaces.”

Also, the communique from T2, which was seen by WeeTracker, claims that second-hand clothes imported into Kenya are routinely treated, fumigated, and transported for a period of weeks under varying temperatures and conditions.

“All shipments are issued with a Certificate of Conformity by leading international inspection companies such as SGS, under close supervision by KEBS,” a part of the company’s statement reads.

Still, the KEBS is showing no sign of shifting ground anytime soon, and if the idea is to keep the ban in place until COVID-19 becomes past tense, the impact of the mitumba trade disruption could be quite devastating.

Image Courtesy: EXX Africa