Is Nigeria Sweeping A Data Leak Like South Africa’s Biggest Breach Under The Rug?

It’s just another uneventful Tuesday and Joan, a 27-year-old Nigerian primary school teacher, is going through the motions. With schools still shuttered because of the pandemic, she’s been out of work for months and her days are a bore.

But this was to be no ordinary Tuesday because around midday, her phone rings — it’s a strange number but she’ll take misplaced calls all day so long as it breaks the boredom.

Now on the phone with a strange caller who claims to be an account officer from her bank, Joan is led to believe that there is an issue with her bank account and card.

This strange caller, who is actually a scammer, has not only a phone number but also knows Joan’s full name, date of birth, address, bank verification number (BVN) which is essentially her social security number, her next-of-kin, email, occupation, as well as her place of work. With all that data and some good acting, the caller seems authentic.

The scheme eventually reaches a point where the caller requests Joan’s card details. This is when she realises she’s getting pawned. Playing along, she supplies bogus card details just for the fun of it. The caller then asks that she go change her ATM PIN but to first supply the old PIN so that her card can be updated remotely.

Eventually, the caller tires out sensing that Joan is no sucker. The call abruptly ends. Joan shakes her head and with a wry smile says: “Not today.” She didn’t get played but there’s no telling how many unsuspecting people have fallen for that trick.

Indeed, when the Nigerian government announced palliatives amid the pandemic, many Nigerians got calls from strangers armed with solid data and with the same M.O, claiming to be government officials responsible for distributing financial aid. People got played, bank accounts were emptied.

In today’s Nigeria, calls like the one Joan received on that Tuesday have become quite common. It appears a great amount of private information belonging to Nigerians is now in the hands of scammers who are now fishing for suckers and probably succeeding more often than not. Such data is also handy for identity theft.

It’s even more concerning that the authorities are not fessing up. None of the institutions that are privy to such sensitive data has communicated any breach, even though it’s obvious something is terribly wrong.

None of the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA), or the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), or the Consumer Protection Council (CPC), or the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC), or even the banks, has admitted any such data compromise.

At the moment, it appears a leak that is probably of the same magnitude as South Africa’s largest-ever data breach is being swept under the carpet by Nigerian authorities.

In October 2017, South Africa suffered its biggest data breach as millions of personal records of anyone, dead or alive, with a South African ID number (a 13-digit identity number) were leaked on the internet.

The 27GB data file contained information ranging from ID number, marital status, income, company directorships held (and previously held), employment details as well as property ownership information.

More than 30 million unique records were involved. Troy Hunt, the security consultant who first revealed the break, said the leaked information even contained employment details of his first-ever job as an intern in 1998, with contact details too.

It is possible that something similar may have transpired in Nigeria but Nigerian organisations have kept it under wraps due to trust and cultural issues associated with disclosing cyberattacks — not the best of options, in any case, since it would really help to make it public.

South Africa does get the most mention when it comes to cyberattacks on the African continent but it’s probably because, unlike Nigeria, the country seems to be quite open to reporting it, more than Nigeria is at least.

In most recent memory, Nedbank, one of South Africa’s biggest banks, suffered a data breach in February 2020 affecting 1.7 million customers. That same month, state-owned power company, Eskom, acknowledged a malware infection and possible data leak.

Back in October 2019, the website of the City of Johannesburg suffered a ransomware attack for the second time in four months. Both attacks were carried out by the same hackers who demanded a ransom payment of 4 Bitcoin (USD 30 K at the time). They had threatened to publicize sensitive data if their demands are not met.

By contrast, the Nigerian scene seems to refrain from admitting such breaches even though Section 21 of the Nigerian Cybercrime Act unequivocally states that individuals and organisations must report cyberattacks when they happen.

Most recently, one of the top-rated banks in Nigeria was forced offline for more than 96 hours and up till now, no one really knows why. Other reports of high-profile data breaches involving a popular Nigerian airline and a National health platform were barely acknowledged.

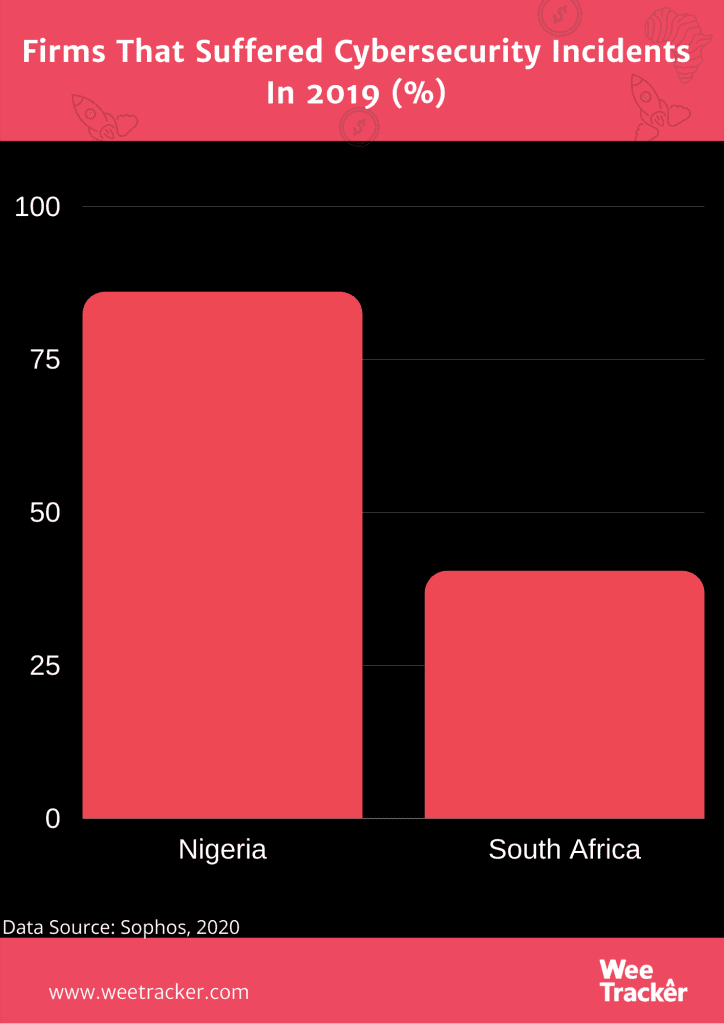

Throw in the fact that a recent report by Sophos suggests that Nigeria actually suffers the most cyberattacks on the African continent — actually the second-highest globally after India — and there’s much cause for concern.

Featured Image Courtesy: CNN