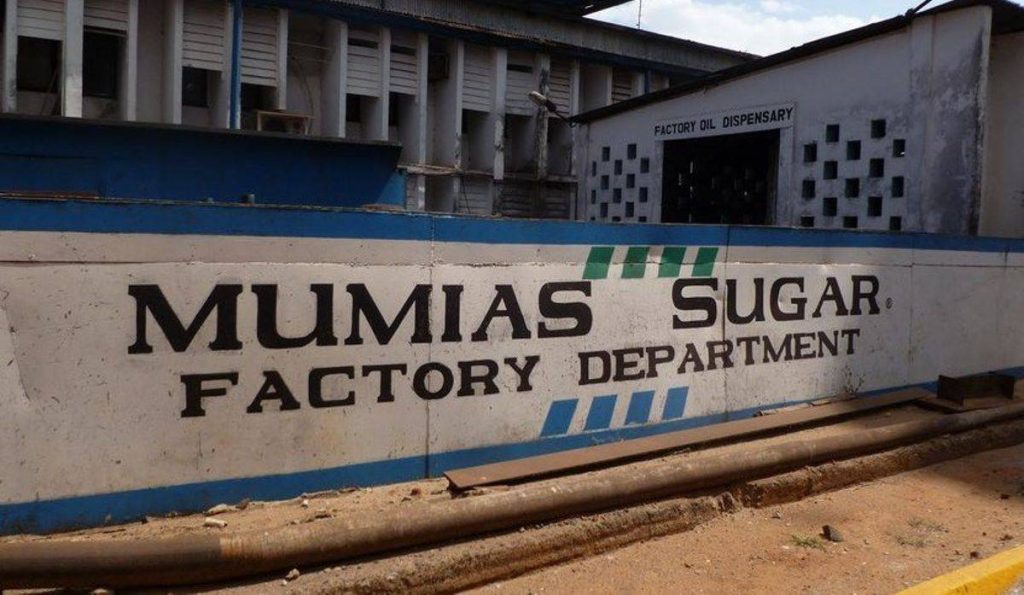

47 Years In The Breaking: How Things Went From Sweet To Sour For Mumias Sugar Company

“The mixing of politics and business not only is detrimental to politics, as is frequently observed but even much more so to business,” one Ludwig von Mises correctly said and I cannot agree more with him on this.

The story of the Mumias sugar company is still difficult to even contemplate. But one thing that has remained evident is the fact that politics has played a huge part in the slow and painful fall of the Kakamega-based plant.

Normally, declines can be dodged, detected and reversed, but for Mumias sugar company things seem to be getting from worse to worst despite several attempts to have it revived.

Well, there are failures that are so enormous that we would typically think that there’s no light at the end of the tunnel, but for Mumias, the hope for a thriving future has always been there, more so given how big the company was.

Growing up in the ’90s, the only sugar brand we used was Mumias, it was always obvious whenever I would be sent to get sugar from the shops it had to be Mumias. The brand not only dominated the sugar market but also ruled supermarket shelves.

There is no doubt that Mumias was Kenya’s market leader, accounting for over half of total national output.

I do not know of what quality sugar is like but Mumias to me looked top-notch with its tiny and most uniform crystals which came in more convenient when baking cakes.

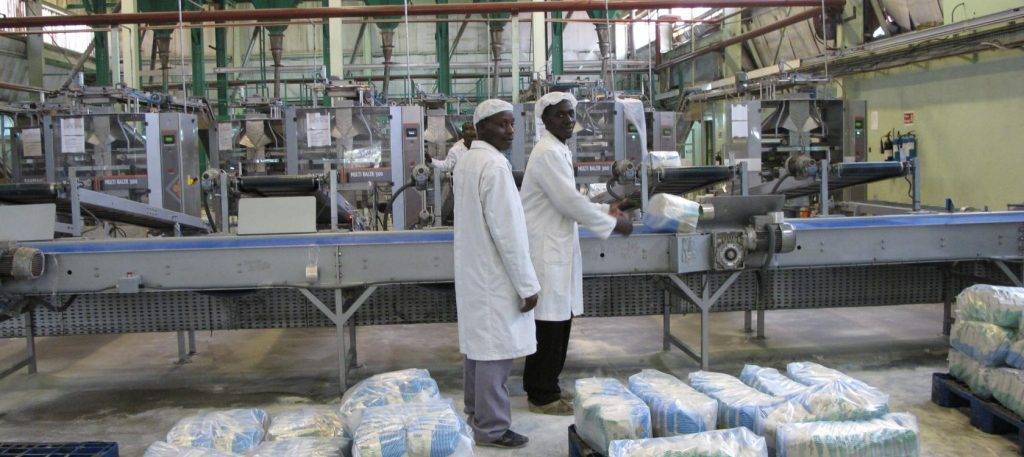

At its peak, Mumias Sugar was the largest sugar producer in the country producing up to 300,000 tonnes a year, which is half of today’s production of all the operating factories.

Data shows demand for the commodity has been increasing year after year while production has been decreasing. Kenya produces 600,000 tonnes of sugar annually and it relies on imports to meet its demand that currently stands at 900,000 tonnes.

Sugar imports grew by 70 per cent in the first nine months of 2019 in comparison with the same period last year as the country relied majorly on imports to cover for the deficit. Between January and September this year, the country imported 324,055 tonnes compared to 190,084 tonnes imported the same time the previous year.

The company which was once a shining beacon of hope in Western Kenya is now a mere spectator of its older self. Mumias town which was once vibrant; teeming with traders and buyers is slowly turning into a ghost town as the movement of cash is no longer as vibrant. The myriad of activities that took place in Kenyan town has toned down significantly pushing residents to a life of grinding poverty. Isn’t it just interesting how one company can almost kill the sparkle of a once-thriving town?

The picture is even bleaker for farmers and workers who have lost their source of income. The farmers are demoralized and most of whom are convinced that Mumias will never be on its feet again. Mumias Sugar owes farmers and employees KShs 1.4 Bn.

During Mumia’s heydays, sugarcane farmers from the Mumias sugarcane zone reaped big and most of them became millionaires, their livelihoods fully depending on the reaps from the once giant sugar company.

Mumia’s story remains a bitter tale that weighs heavily on farmer’s backs. Every day, they watch in pain the decomposing and disintegration of a once vibrant factory that was their source of livelihood.

The factory which was once a busy hub has become quiet. Inside its humid and sticky walls, where workers spent long days labouring over machines refining raw sugar, the machines stopped and workers laid off.

The premises have almost been left to monkeys. Passing by there, you may think they are the new owners as they run around the deserted buildings.

Only revenue source shut down

In 2009, Mumias Sugar constructed a Kshs 3.5 Bn ethanol distillery plant to diversify its revenue base.

Since the ethanol plant started being operational, Mumias has been banking on ethanol to keep its head above the water. It has been a main source of funds for the ailing miller.

Weetracker tried to reach out for a comment from the company regarding the closing of the distillery and the official we spoke to said: “it has not really been closed, we can say it’s on a recess” before hanging up the phone.

We also tried to reach out to three of the company’s insiders but our efforts bore no fruits.

Following the closure of the distillery, farmers are now more worried since the production of ethanol which was the only activity left taking place has also been stopped.

Receivership

The debt-ridden miller was last month placed under administration after defaulting loans owed to Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) amounting to Kshs 545 Mn. The bank was, however, blocked from auctioning assets belonging to the company by High court.

After the takeover, KCB appointed Ponangipalli Rao of Tact Consultancy Services to act as receiver manager on September 24.

Notably, the miller which is majority-owned by the government has not been producing sugar for almost a year now.

Where did the woes begin?

After the entity was privatised, farmers’ shares were broken down and shared with individual farmers, a move that was intended to ensure the farmers did not have a unified voice.

Under the new management which took over the wheels after privatisation, farmers were mistreated. Given the bad treated they got and the fact that they were no longer paid, some of whom opted to uproot cane and focus on growing other crops while others moved to work with Mumias’ competitors.

Not long after, the company experienced a severe cane shortage that took a toll on the firm’s earnings. The situation got so bad until the miller was unable to pay its bills.

After farmers failed to receive their dues, the company lost farmer loyalty which then led to low production and underutilization of the factory operations.

Notably, the acute shortage led to under capacity operation of the factory and low production since, at some point, the plant had to be shut down for three months to allow sugarcane to grow and manage the raw material costs.

Mismanagement is also to blame for its financial difficulties. An audit by financial consultancy firm KPMG earlier indicated that there was massive misuse of funds, pilferage, and tender manipulation that cost the miller Kshs 1.1 Bn through illegal sugar imports.

The shortage of cane was also exacerbated by the abolishment of cane zoning by the Ministry of Agriculture and by the lack of a legal framework to control cane sourcing. The creation of sugarcane zones is normally aimed at binding contracted and private cane farmers in specific areas to specific millers.

Government Bails Out

The government recently announced it has done all it could to revive the debt-ridden company adding that it is time another strategy is adopted.

The Deputy President said that mismanagement is to blame for the bailout cash, “We brought the first KShs 2 Bn here and it went under, we added another KShs 2 Bn, again it was misappropriated. We looked at that and said enough is enough,” he said.

The government which owns 20 of share in the troubled Miller which has announced plans to offload it’s shareholding in the troubled Mumias Sugar company to the county government.

Will it ever stand again?

Questions linger on whether Mumias Sugar Company will ever roar back to life again.

Different key players are currently looking into ways the miller can be brought back to life.

Deputy president William Ruto said the county government had presented a turnaround plan and should be given a chance to play a major role in the company. The move to have the company under the control of the county government could be a laudable one since the county is on the ground and would be in a better position to monitor the progress. However, the decision does not guarantee a successful revival, if the turnaround is not handled properly, it could turn out to be disastrous.

Gerald Muriuki from Genghis Capital, an investment bank in Kenya told Weetracker that political interference whose effects are mismanagement, corruption and lack of accountability is to blame for the ailing public sugar millers.

“It is hard to argue a case for revival of the miller unless the government completely gets out of this industry,” he said adding that the public millers struggle with “old inefficient equipment, disappointed suppliers, farmers and competition from private millers.”

Regarding delegating the company’s revival to county government and whether it will help in rescuing the ailing miller, Mr. Muriuki argued, “Possibly to a lesser extent given that local government is closer to the ground. However, in the broader context, governments are not known to be good commercial business stewards.”

With KCB’s takeover and also given that the bank’s interest in the miller is to get its money back, Mr. Muriuki says it is going to be extremely difficult to revive Mumias.

From an expert point of view, he says a privatisation plan would do good for the miller.

What next for Kenya?

Worldbank earlier revealed that Kenyans love sugar, which they utilize in their tea. On average, each Kenyan consumes 400 grams of sugar per week, much more Tanzanians for example, who consume approximately 230 grams.

Kenya consumes close to a million tonnes of sugar annually and the bulk of it currently is imported to beat the rising demand of the commodity. The trend has been predicted to continue as the population increases.

In a bid to address sugar shortages in 2017, the government opened the window for the importation of duty-free sugar outside the regional market.

It is highly likely that the country will rely on the imports for a while to beat the demands as there is no clear strategy yet to boost local sugar production.

With regard to Kenya’s being able to produce enough sugar for consumption, Mr. Muriuki said, “It will take a lot of time to improve the viability of the sugar industry in Kenya, especially to the level of exports. Moving from the current production deficit to sugar surplus will take many years unless there are quick and solid structural reforms in the sector, which we haven’t seen yet.”

For Kenya to have less bitter future in regards to sugar production, the sugar sector may need big, few private-owned companies to easily and quickly beat the growing deficit.

Meanwhile, the government may need to also tighten protection measures to protect the country’s nascent sugar millers from the influx of cheap imports.

Featured Image Courtesy: Expose KE