East African Retail Remains A Hard Nut To Crack—Even For ShopRite

East African retail swims in a mix of economic realities and internal mismanagement. Players on that side of the continent have their noses to the grindstone. The sub-region plays host to one of Africa’s most formalized retail markets—Kenya—but a series of events suggest that business in the sector remains hassling.

ShopRite’s Backtrack

ShopRite Holdings, one of the biggest retail players in Africa appears to have found its going to East Africa tougher than expected. The South Africa-headquartered consumer goods retailer is reevaluating its operations in the region. This, however, is part of the company’s wider plan to abandon the markets that have not brought it profits.

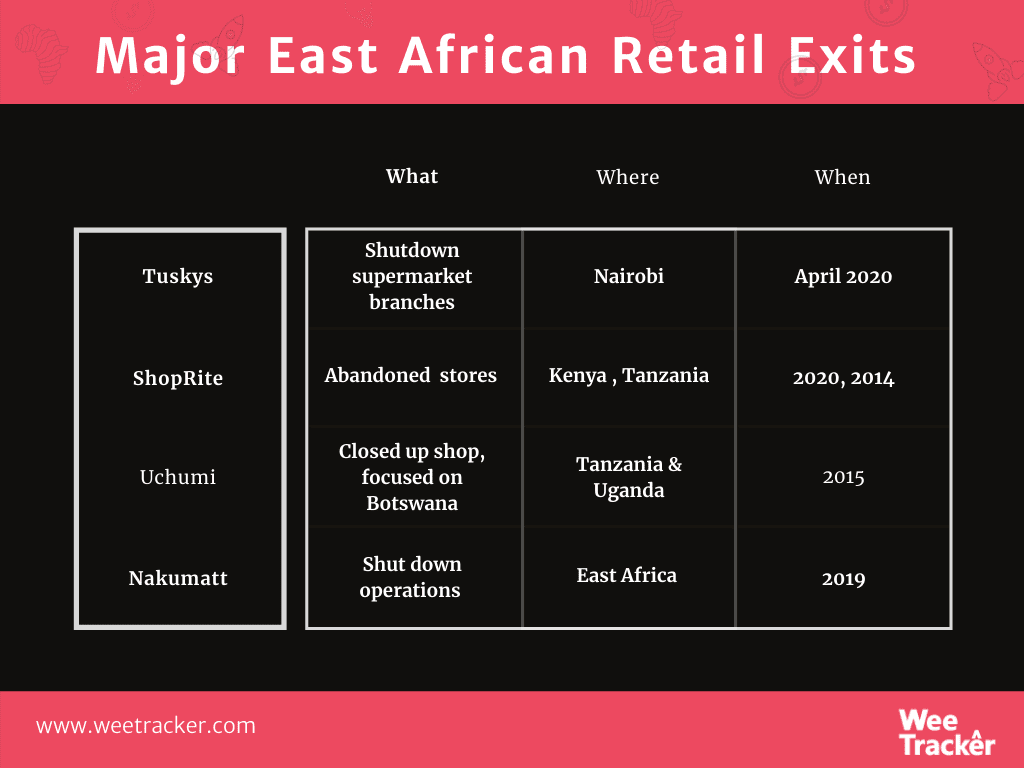

Late April 2020, ShopRite decided to call it quits on the Kenyan market, thanks to the reduction of shoppers due to the novel coronavirus. It shut its Waterfront branch in Karen, resulting in job cuts that will affect 104 workers. Interestingly, the retailer entered Kenya only in 2018 with plans to expand.

Nonetheless, ShopRite’s plight in East African countries transcends the coronavirus. 6 years ago, it exited Tanzania through the sale of its two branches in Dar es Salaam and one in Arusha. The then retail giant Nakumatt—which has since fallen—bought the assets for an estimated USD 45 Mn.

It would appear that since it left Tanzania, ShopRite has been reviewing its operations in East Africa. The JSE-listed firm’s operations outside South Africa account for only 20 percent of its profits. As such, it wants to preserve its investors’ capital by optimizing its existing investments.

More Of The Same

ShopRite pumping the brakes on East Africa isn’t a first. In September 2019, Botswana-headquartered supermarket chain Choppies exited Kenya. The firm found it hard to gain a substantial share of the retail market, save the shake-up caused by other internal problems.

In 2015, one of the oldest retailers in Kenya decided to throw in the towel after years of recording losses. Uchumi, which was founded in 1975 and listed on the Nairobi Stock Exchange, left Uganda and Tanzania amidst owing millions of dollars to suppliers.

East African retail has been presented as promising by some analysts in the past. But, some, like this AfDB report, shows that the 44.9 percent floating middle class in the region does not form a reliable market. In reality, most of them sit on the edge and mostly never buy.

Long queues in malls and retail chains are not scarce. But the middle class visiting these places offer more of presence than patronage. A substantial number of them buy only on a need-to basis, the same amount of which are mosfly window shoppers.

Stuck In The ‘Middle’

Without access to credit, the real middle class would just be 16.8 percent of the whole population. And, it would appear there is an increase in both foot and car traffic. For instance Garden City said that it recorded 1.18 million visitors in Q1 2017, a 15.69 percent jump from 1.02 million in the same period the previous year.

The traffic, nonetheless, does not have a direct impact on the malls themselves, and in turn, sales. The battle for these middle-class shoppers in places like Kenya has become an intense one. Local and foreign retail chains have been aggressively expanding.

Foreign chains like Massmart, Carrefour, Game Stores and others have penetrated the market, posing a challenging competition for local players. They’ve been unable to match these deep-pocketed multinationals with sophisticated supply chains and exclusive online shops.

Pilferage is a general problem. According to Cytonn Investments, retailers are losing up to USD 50 Mn every year to pilferage and shoplifting. Some players agree that the crime is being taken lightly by authorities.

Looking Within

In as much as ShopRite may have very well seen the shortcoming financial outcome of operating in Kenya, these other sets of retail problems in the region are enough addition to make it come to a final exit decision. Even, the retailers there have a long, well-document history of management troubles and governance.

The fall of Nakumatt is one of the most controversial in East African retail. Its recent financial statements by its independent auditor Parker Randall revealed the firm’s rollercoaster ride with cash, borrowings and losses.

Amounts owed by insiders had dropped to USD 9.48 Mn as of February 2018, the period for which the latest financial records are available, according to the report.Totalling USD 28 million, most of the amounts receivable are unlikely to be recovered.

USD 15 Mn or 53 percent of the receivables have been written off by the administrator. In comparison to other firms, the financial report depicts loose corporate governance at Nakumatt. Nakumatt founder, Atul Shah, is being investigated for the loss of more than USD 180 Mn worth of stock which he allegedly wrote off in May 2018 before the firm shut.

International players, however, seem to have the upper hand, as they are mostly exempted from these East African retail struggles. Japanese brand Miniso recently expanded to malls in Nairobi. This, among many counterparts, appear to have the financial muscle to capitalize on the opportunity and get more of the high-end, middle-income market.

Featured Image: Unsplash