African Edtech’s Many Demons & The Result Of The Big COVID Test

With over 1 billion students in 138 countries still out of school with no clarity as to when normal classes might resume, formal classroom education has perhaps suffered the longest-lasting impact of the disruptions triggered by the global pandemic.

Countries have eased lockdowns, airplanes have taken to the skies once again, sporting activities have resumed, international borders have been reopened to tourists, but schools largely remain shuttered across the globe.

Back in April, when the global COVID-19 death toll was still under 350,000, estimates from UNESCO suggested that 80 percent of the world’s learning population had suffered class disruptions due to virus containment measures.

Suddenly, technology-backed online/remote learning became the go-to remedy, and education technology (edtech) waltzed into a boon, or so it seemed.

Well, it was always just a matter of time before the honeymoon gave way to the jury being out on whether edtech over-promised and under-fulfilled, or vice-versa.

Much ado about edtech

Edtech has all the trappings of a tool tailor-made for such a situation; something that would keep classes going despite the closure of schools worldwide.

“It is true that the pandemic presented both a huge problem and an opportunity. For those who had begun a journey in online education, it created an acceleration of opportunity and decisions. It turned technology from a nice to have — merely a consideration — into an essential item to offer education,” Brett Commaille, Director and Investment Principal at South African VC firm, Hlayisani Capital, told WeeTracker.

In many developed regions of the world where technology has long assisted the propagation of education considerably, the switch to e-learning was relatively easy — maybe even a no-brainer too.

However, in developing regions like the African continent where quality basic education itself (not to mention tech-supported e-learning) is still a struggle, it’s a bit of a different story.

In fact, a report by Brookings Institution claimed that less than 25 percent of low-income countries provided remote learning opportunities in the midst of the pandemic, compared to an adoption rate of about 90 percent in high-income countries.

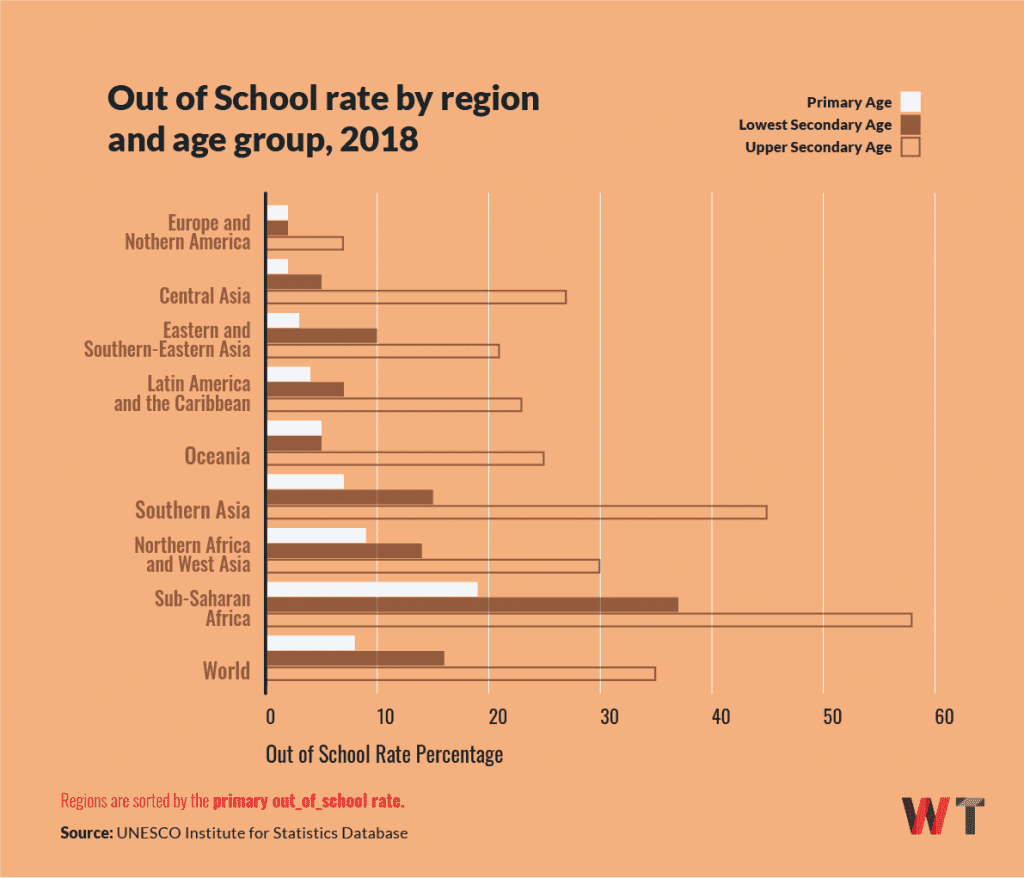

With some 60 million children in sub-Saharan Africa out of school (even before COVID-19 happened) and another 30 million at risk of never going to school — coupled with deep-rooted deficits in qualified personnel and infrastructure — edtech was never going to suddenly solve all the problems and save the day.

But oddly, the pandemic did finally give the oft-neglected subject that is edtech a rare shot at a big audition in Africa; something of an impromptu litmus test which finally gave African edtech the sort of attention that had eluded it for far too long.

So, what’s the deal with African edtech?

Africa has an education problem, it was there before the pandemic and it will have probably worsened post-COVID.

According to the World Bank, 87 percent of children in sub-Saharan Africa are learning poor and are deprived of functional skills in an ever-changing labour market. Even in South Africa, the continent’s most industrialized economy, only 40 percent of pupils finish high school, according to UNESCO.

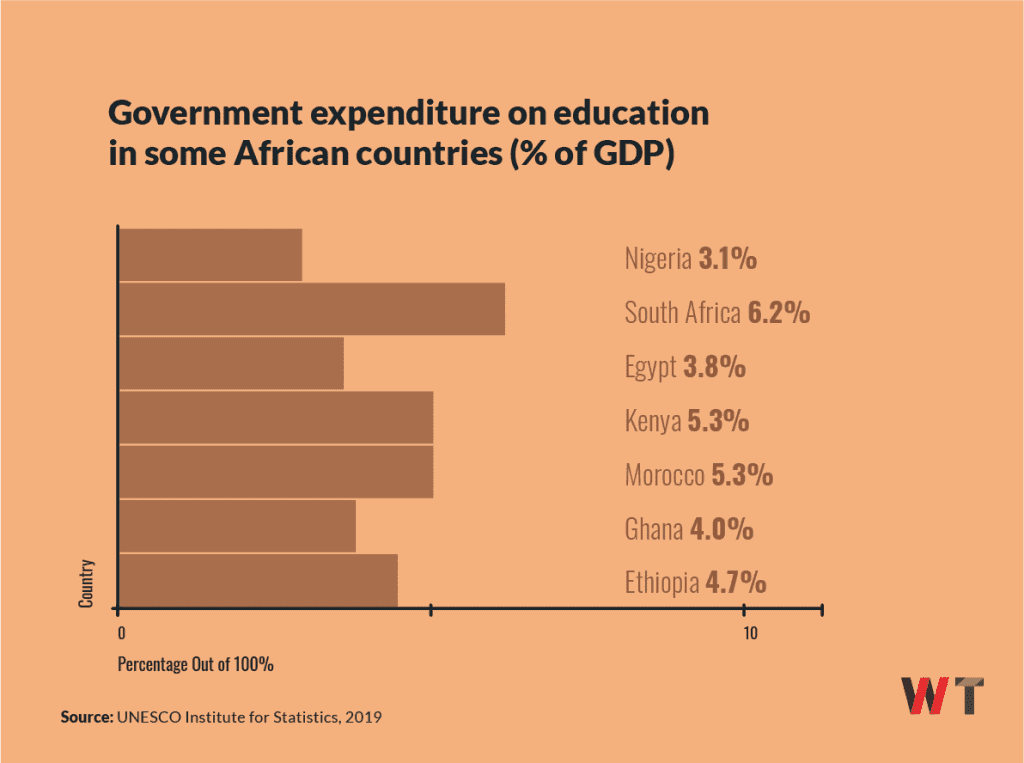

Although the African Development Bank (AfDB) reports that African governments spend about 5 percent of GDP on education, which is the second-highest of any region, access to quality education is fraught with problems as there are still huge deficits in infrastructure and personnel.

According to AfDB, the continent currently faces an annual gap of USD 40 Bn in education financing.

Besides that, at the primary level, there is on average 1 trained teacher per 60 pupils across the region, compared to a global average of 27 pupils per teacher. At the secondary level, the ratio is slightly lower, with 44 students per teacher compared to 20 per teacher globally.

These shortcomings, coupled with a soaring population of young people in the learning age bracket, have created an incentive for the deployment of innovative solutions focused on democratizing quality education. However, the hurdles remain as high as they come.

Yet, many brave the storm.

Sim Shagaya, founder of uLesson, an edtech venture launched last year, explained that certain ongoing trends make a case for tech innovation around education delivery in Africa, though by his reckoning, African edtech is still in its infancy, and there are challenges.

“Digital technology allows you to provide quality education on a greater scale than older forms of providing education. For instance, Nigeria has a really bad teacher-to-student ratio, it’s about 1:80, I even read about a school where it’s 10 teachers for 1,100 students. That is just a recipe for the students not learning at all,” said Shagaya.

The 2018 World Development Report does point out that in low- and middle-income countries, fewer than 1 in 5 primary schools kids are proficient in math and reading.

“With digital technology, you can take quality teachers and make them available at scale with low marginal cost. It gives more efficiency, drives affordability, and standardises quality.”

Shagaya added, “There are many underlying trends that would drive the success of edtech on the continent. There is an increasing reliance on private schools and that is derived from the fact that the government, despite spending a lot, is having sort of a diminishing return effect on education.”

“Even lower-income parents are increasingly choosing private education. Connected to that trend is the fact that private education is seeing increased investment in technology, and that’s technology across the board whether it’s content and software like uLesson or hardware like tablets and computers,” he said.

The above trends seem to be catalysing the proliferation of edtech startups (now up to 362 of them in Africa, as per data from AfriCo). This is accelerating the emergence of an edtech market that was reportedly worth USD 792 Mn in 2018 and is projected to hit USD 1.8 Bn in 2024.

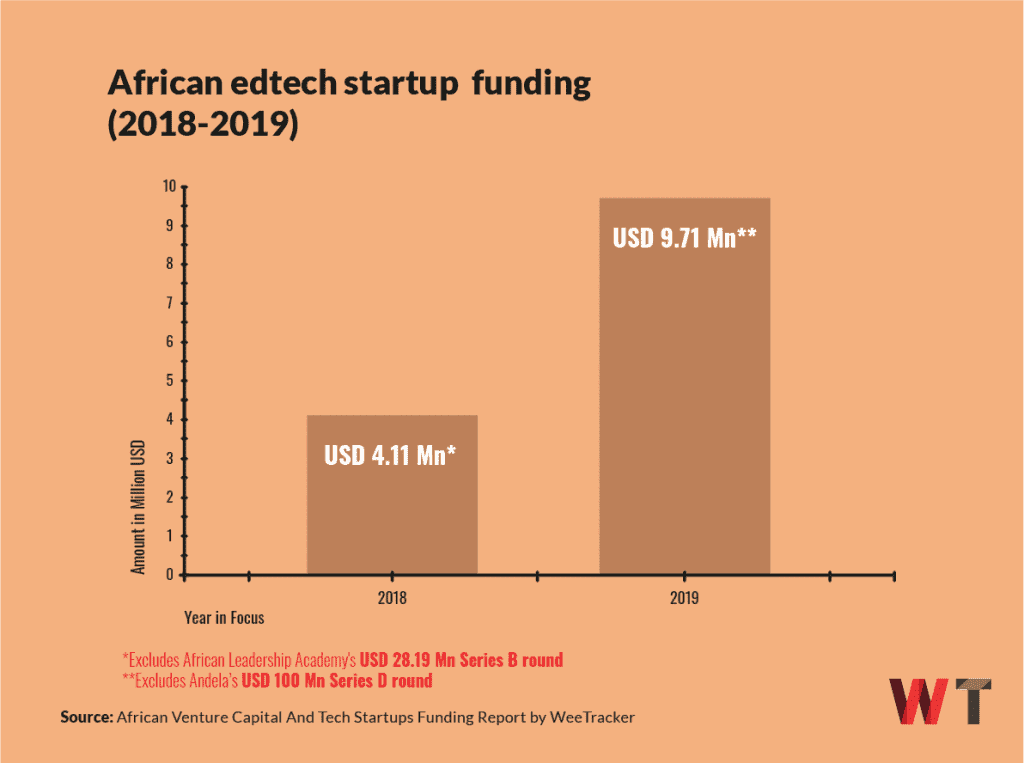

However, not to get too carried away by those debatable numbers, edtech has, in fact, barely scratched the surface in Africa. Partly due to question marks over its viability, edtech gets far less attention and consequently attracts much less venture capital relative to other hotspots like fintech, mobility, and e-commerce.

The lukewarm interest in African edtech can be attributed to the fact that most of the startups playing in this turf typically develop technology-dependent remote learning platforms that usually require hardware, internet, and electricity.

These elements make up a trio of things that continue to be pain points in Africa. It is perceived that the many barriers, which have so far stifled edtech in Africa, make it unattractive to funders.

But when schools were shuttered after the pandemic struck — effectively suspending formal learning for over 250 million primary and secondary learners in Africa (not to mention those in tertiary institutions) — e-learning seemingly got a leg up. But did African edtech startups grab the opportunity?

Gauging the edtech effort

It might be too early to measure the extent to which African edtech startups have gobbled up the chance and made a case for their increased relevance in the post-COVID era. But it’s near-certain that a good number of them have recorded unprecedented growth spurts.

“We had started planning on building uLesson a year before the pandemic struck and we had actually launched the product a month before the lockdown started,” said Shagaya.

“We were already seeing good traction before the lockdown happened. But once the lockdown happened, it became really clear that the pandemic was providing a tailwind that was sort of pushing us faster than we would have gone.”

As he further mentioned, the closure of schools fuelled a surge in inbound interest from customers; over 20X growth in customer growth since March, according to him.

“If I had to quantify the growth since the lockdown, we probably made the amount of progress that would have taken us 18 months. COVID was like an accelerant, a catalyst,” he added.

It’s a similar submission from Commaille whose firm teamed up with Knife Capital in the USD 2 Mn funding round closed by South African edtech company, Snapplify, in September 2019.

“Our portfolio company, Snapplify, worked with publishers to make their textbooks free for the year. This led to record signups on Snapplify, more than 400 schools in one day in fact. For many, this is their first foray into an online education product,” said Commaille.

“Opennetworks, another portfolio company, partnered with Google to take a group of schools onto Google classroom – a comprehensive platform for managing students and teaching online – training teachers in using tools for online education. Again, many of these schools had not contemplated online education,” he added.

It was as though African edtech startups suddenly sprang to life. Across the continent, platforms like eLimu, Ubongo Kids, SimbiBot, M-Shule, Eneza Education, Gradely, and Zeraki Learning, among others, seem to have flourished in these times.

But whether that indicates a major paradigm shift or a temporary superficial dent is a different matter altogether.

Paradigm shift or temporary dent?

The edtech boom has been talked about the world over. But there’s a reason several African governments are far too willing to take a stab at mass education through fundamentally flawed mediums like local radio and national TV, rather than latch on to the potentially better learning experience offered via edtech.

It’s because edtech has an accessibility problem, no thanks to the somewhat intractable infrastructural deficits that blunt its impact.

As these deficiencies are prevalent in Africa, edtech comes across as more of a glossy contraption in these parts; something for a privileged few, rather than a functional solution for universal basic education.

Seeing as scaling edtech in the midst of the bottlenecks in these climes is a big challenge, the sector remains largely unattractive to funders.

In fact, African edtech startups have been hamstrung by the paucity of venture capital, raising small amounts compared to a hotspot like fintech which accounted for over 50 percent of the USD 1.34 Bn collectively raised by African startups in 2019.

“Edtech companies often solve a specific issue, but their solution cannot be implemented until many of the larger systemic issues are addressed. You can build an incredibly innovative application to teach maths, but if the school has no electricity, no devices, no data connectivity, it cannot be used,” Commaille pointed out.

“Many solutions end up thus only being suitable for elite or private schools. Entrepreneurs and businesses who understand this situation and develop solutions that operate within this challenging environment are rare and worth supporting.”

More so, there are those in the industry who believe that the future of edtech is dependent on politicians because of the connections the sector has with the “system.” It’s a sentiment Commaille shares.

“Politics and corruption seem to plague so many of the [edtech] projects. Because of the numbers involved, they [edtech startups] all seem to be doomed to failure in a year or two. And the competent businesses, with a track record, are often only called upon when it’s time to clean up the mess and the budgets are drastically reduced,” he remarked.

African edtech’s many demons

The challenge in propagating the mass adoption of edtech in Africa is compounded by systemic issues.

For starters, more than 800 million people in Africa lack access to the internet, according to the 2020 Digital Economy Report by GSMA.

As per the Digital 2020 Global Overview Report, only 33 percent of Africa is online. Internet penetration is currently 39.3 percent; the lowest among global regions. With this, online learning appears to already be one-nil down from the start.

Factor in the relatively low mobile access and high internet costs relative to household income and there are yet more obstacles to edtech’s attempt to go mainstream.

Electricity is also a big challenge. As edtech solutions typically require a reliable power supply, there’s a mountain to climb. At the current 43 percent electricity access rate, Africa trails the global access rate of 87 percent by half.

Additionally, there’s the poverty statistic from the World Bank which suggests 85 percent of the African population lives on less than USD 5.50 a day. To lower the bar even further, 70 percent live on less than USD 1.90 daily.

For context, uLesson’s subscription fee, for example, is around USD 6.00 a month. Thus, any talk of scaling edtech in present-day Africa has the feel of a Herculean task.

All the aforementioned elements, if optimally available, create the dream clime for edtech. But if there’s some deficiency of those key elements — as is generally the case on the continent at present — edtech is doomed to be little more than “existing and barely functional.” In other words, edtech comes off as s0me shiny, sexy tech that is just nice to have.

Better days ahead?

Notwithstanding, there’s some optimism. Shagaya, for instance, stays bullish on edtech as he does see some positives amid the hurdles.

“Internet penetration into schools is going up; internet cost is actually dropping dramatically. In terms of device pricing, we’re seeing 1-gig RAM or higher devices coming to the market now for less than USD 100. The big intractable issue for edtech is electricity, but that applies to everything and everyone,” he said while noting that the demand for quality education is strong.

“The willingness to spend on education is typically high. I’ve seen data that suggests households in high-income countries like Sweden and Switzerland spend about 5 percent of household income on education, and part of that is because the public school system works. In some countries in West Africa, it’s 25 percent,” Shagaya emphasized.

As he put it, the apparent inelasticity in demand for education suggests people are willing to spend on education even though it means accommodating some ancillary costs. And according to him, that counts as a positive for edtech.

On his part, Commaille emphasised that “we suffer from a lack of quality educators, but using technology can suddenly multiply the reach of an excellent teacher tenfold. Interventions can be specific to each child, even in high volume classes.”

“So many things are possible, but it takes a concerted effort from government and education departments, to stop merely paying lip service, and start working with companies who have a proven track record of implementation,” Commaille reiterated.

Another critical part of the puzzle is for edtech startups to figure out how schools buy, how parents buy, how companies sell to these buyers, and how they can best fit into that system.

As the investor explained, “Schools don’t want salespeople knocking on their door for every little application and subject tutorial. Partner with the platform players and ensure you find a tested business model that works at scale across various environments. If you are unsure of how to do this, track down those who are in the market and be prepared to learn.”

But there’s plenty that needs doing on the part of the government, schools, and even edtech ventures themselves if e-learning is to progress to a point where it becomes a key part of schooling in Africa.