54 Of 55 African Countries Have Signed The New Free Trade Agreement – Here’s Why Eritrea Refuses To Okay The Deal

Out of 55 countries, Eritrea is the only African state that has not signed the AfCFtA agreement as its repressive regime continues to hold out on signing the deal. And this is why.

Nigeria and Benin respectively became the 53rd and 54th African countries to commit to the much-talked-about African Continental Free Area (AfCFTA) agreement; an initiative of the African Union (AU) that is geared towards creating one boundless continent-wide market of 1.2 billion people worth around USD 2.5 Tn — the largest ever in terms of member states.

After holding out for so long — supposedly to weigh the pros of cons of the agreement — both countries finally opted to put pen to paper at the Extraordinary AU Summit which took place in Niamey, the Nigerien capital, on Sunday, July 7. This means that 54 out of 55 African countries have now okayed the deal, with Eritrea currently standing as the odd one out.

Source: theafricareport.com

And one might begin to wonder how it is that a small country in the Horn of Africa is still holding out on a deal that has been given the green light by several African powerhouses, and why. Well, nobody really knows. But there are a lot of theories that could be put forward to explain why this “Gen-Y nation” is not just dragging its feet with respect to the whole deal but is now being defiant, apparently.

In truth, nobody can really force the hand of the one-party state if it feels like the agreement isn’t worth its while, and it appears that the country’s government is holding out because the deal does not support its best interests. But those must really be some “interests” given that 54 out of 55 countries are missing it.

Or maybe all of it is a ploy to get everyone’s attention as they are now, because, common, how often does Eritrea get on the news for reasons good or bad? Well, at this point, they’ve gotten everyone’s attention and it sure looks like it’s going to be way more than five minutes of fame.

The AfCFTA agreement has been hailed as historic in that it signals a radical gesture that can potentially disrupt the structural dependency of Africa on its former colonial powers. It is anticipated that removing tariffs, which constitutes a core principle of the agreement, could increase intra-Africa trade by 52 percent by 2022 from the current 15 percent.

Source: Afreximbank

The agreement could be viewed the first stepping stone towards a European Union-style free trade area that allows free movement of people and a single currency. The initiative by the AU has been lauded as a bold move that would transform African economies by boosting local manufacturing and trade between sister states.

Ordinarily, this sounds like a plan everyone should be happy with, and it looks like everyone is except Eritrea. And as people across the continent ponder over the matter, there are possible explanations, not unconnected to power and politics.

Isaias Afwerki has ruled Eritrea since it gained independence in 1993 and to this day, his party; the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), is the sole legal political party in Eritrea. In many ways, the party has had the country under its thumb for 26 years running.

In all that time, the ruling PFDJ party has made a number of extraordinarily sharp ideological and policy turns, most times on an ad hoc basis. At one point, it was all for the hegemony of the United States, extolling the U.S. for its economic policies in Africa and its stance against terror. Then, not too long after, it was raising its voice against the dangers of such hegemony and the negative impact of the war on terror.

At another point, the government was waxing lyrical in favour of constitutional governance with all the liberal trappings of free multi-party elections and free press. And the next minute, it had shifted position with talks of the electorate not being mature enough to assume citizenry responsibilities; talk of shifting the goalpost.

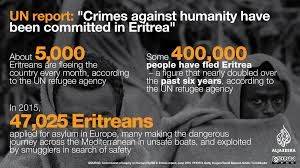

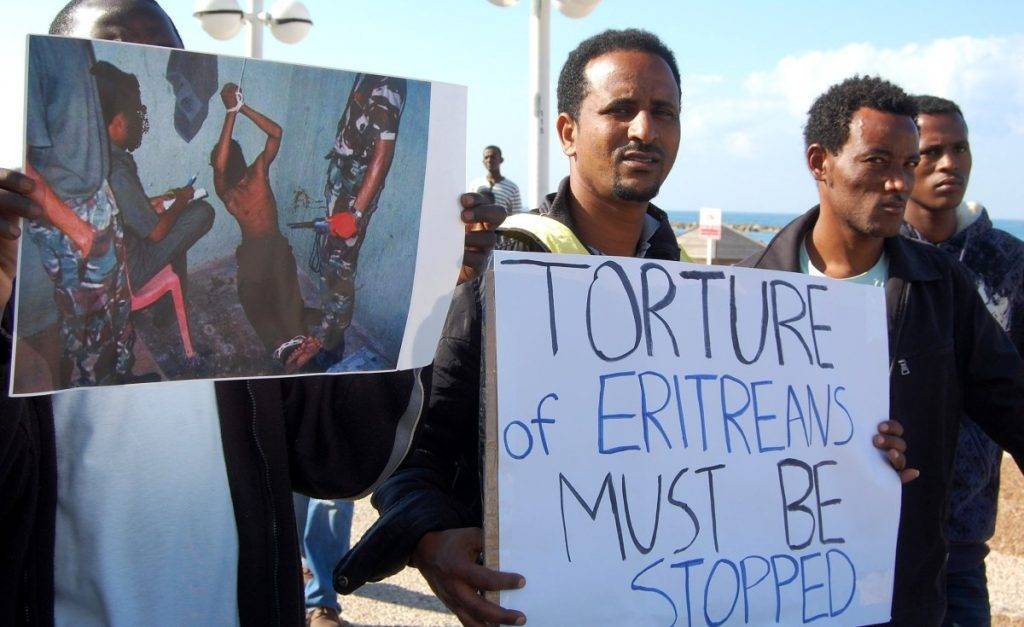

To put things into perspective, the country’s government has been cited for human’s rights violations by the United Nations and Amnesty International. As a matter of fact, under the government of Isaias Afwerki, Reporters Without Borders has ranked Eritrea last in its Press Freedom Index for eight years in a row. That shows how far away the country leans from all that talk of freedom.

In essence, it has all been about saying one thing and doing another with the Eritrean government, even with respect to its economic policies. Citing one of its post-independence foundational economic policy documents — the November 1994 Macro Policy document – the PFDJ’s stance is actually in favour of a thorough neoliberal economic framework, which is what the AU’s proposed AfCFTA agreement pretty much stands for.

The said economic policy document envisions making Eritrea a hub of competitive international financial institutions, with “liberal internal and external trade regime” that enables the country to participate in “regional bilateral and multilateral trade and economic cooperation.”

But ironically, that’s precisely what the AfCFTA deal is now proposing and what the Eritrean government is now refusing. What has happened between 1994 and now is anyone’s guess — things have changed and it appears the Eritrean government has long abandoned that ideology, as it so often does.

When the PFDJ drew up its first economic policy, it was looking to adopt some sort of uncritical and wide-eyed approach in its quest for the glossy appeal of a neoliberal economic agenda.

But times have changed and the government is now looking to manage an extremely autarkic black market-dominated economy that is dependent on a fledgling mining sector and agricultural projects that do not offer much promise. This is the context from which Eritrea’s absence in the AfCFTA agreement should be looked at.

So, why did the PFDJ make a sharp turn from its initial economic policies and opt to shun major regional economic cooperation schemes such as the AfCFTA agreement? Why did it suddenly become wary of the perils of a neoliberal economy (something it once championed) and resolved to extricate Eritrea from the implications of a united economic front?

One might be tempted to dish out the benefit of the doubt but considering the spasmodic manner in which such policy shifts happen, it might prove more profitable to look elsewhere for an answer.

The shifts in economic policy have been typically called by President Afwerki on a whim, without public and institutional debates, and the current decision to exempt Eritrea from an organised African economic front could be viewed as a move to further prop up his power on the local front.

As the current Chief of Staff, General Filipos Weldeyohannes, stated in a meeting he held with government employees, who were forced into military training and dam construction at Gergera, in June 2015, the developmental and security goal of the government is to “control the population like the fingers of one’s hand.” And this could well be another way to achieve that.

For the current Eritrean administration, the economy is yet another site of governmentality, and this is why it stands against any ‘free’ economic regional schemes, for it is wary of undoing its propaganda projection of Eritrea as some kind of “enclosed garden” where its inhabitants are too preoccupied with juvenile celebration of mediocre projects to realise what they are being stopped from having. Why Eritrea has not signed the AfCFTA agreement? It’s mostly down to repression.