Even African Countries With No Lockdown Or Covid-19 Cases Won’t Escape Recession

The outbreak and adverse effects of the novel coronavirus pandemic is putting the world’s economies on the back foot. The predicted loss of trillions of dollars will usher economies into a collective recession, including countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Developing countries, a host of which are in Africa, houses two-thirds of the world’s population. They all face unprecedented damages from the pandemic, but is there any exception?

Corona-Free & Life As Usual

Some supposedly lucky countries like North Korea, Turkmekhstian, Solomon Islands, and Samoa are yet to record any cases of coronavirus. In Africa, the landlocked country of Lesotho in the southern part of the continent, appears to currently solely share the same blessing, although this has been blamed on testing inefficiencies.

Comoros, a volcanic archipelago off Africa’s east coast, was previously in this same COVID-19 free category, but on April 30th verified its first case. Now, the tiny mountain kingdom has 3 cases. As such, the country, like Comoros, has not felt the need to enforce a lockdown.

In the continent, however, Lesotho and Comoros are not the only countries that have not joined the strict lockdown bandwagon. While South Africa executes what is said to be one of the longest coronavirus confinement periods in Africa, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Malawi and a handful of others relent.

It is either a state of emergency in some or a nightly curfew for others, but these countries have not seen need to fully restrict movement. As such, businesses are still open, people are still attending churches in some, and life is almost as though there’s no immediate health threat.

It is also life as usual in Comoros because, apparently, there is not enough cases to confine citizens to their homes. Interestingly, the economy of the country is based on subsistence agriculture and fishing. Also, it has inadequate transportation links, a young and rapidly increasing population, and few natural resources.

Nevertheless, it is important to mention that the British-style coronavirus lockdown has proven ineffective for Africa. Restrictions are being eased in countries like Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa, but confirmed cases are spiking while economies suffer.

Escaping Recession

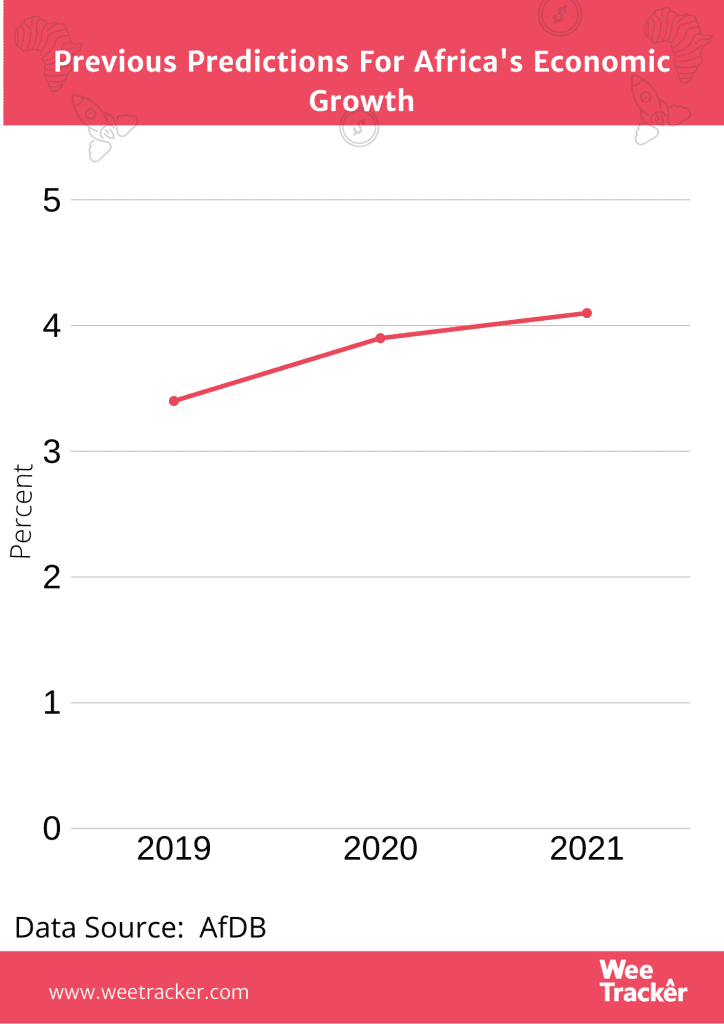

The World Bank, IMF, United Nations, and even McKinsey seem to all agree on one thing: recession looms for Sub-Saharan African countries. One forecast is that economies fall sharply from 2.4 percent in 2019 to -2.1 to -5.1 percent in 2020, ushering in the first recession in the region over the past 25 years.

According to UNCTAD, advanced economies such as that of China and India have put together massive government packages which, according to the Group of 20 leading economies (G20), will extend a USD 5 Tn lifeline to their economies. As a result, these two countries, despite experience sharp economic growths, will escape recession.

According to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook (April 2020) GDP growth in China will go down from 6.1 percent in 2019 to 1.2 percent in 2020.

For India, economic activity will slow down from 4.2 percent in 2019 to 1.9 percent in 2020. This is a massive growth deceleration for two countries that have led the growth of emerging markets in the past decade.

However, there hardly is an escape for Sub-Saharan Africa, even the country that had no virus cases or the ones that have not enforced any lockdowns. The region’s largest economies are not falling into recession only because of the coronavirus outbreak.

Domestic Weakness

On the matter, the World Bank told WeeTracker that domestic weaknesses as reflected by the present low investor confidence will add to the factors that will contract the region’s growing economies.

“According to IMF and WBG projections, it can be the case that some countries may escape recession, especially those whose domestic sources of growth are more resilient and have enough policy space to support the economy,” the international financial institution said.

“However, the uncertainty on the persistence of the pandemic, as well as it economic implications, may lead to downside revisions on growth projections for 2020,” WB added.

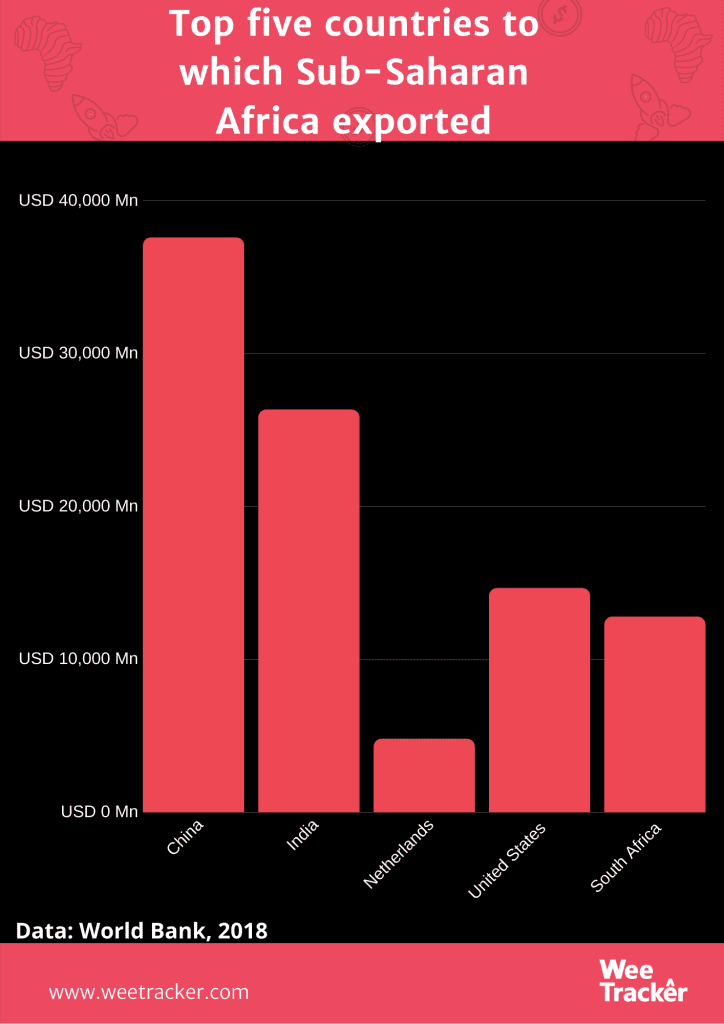

The decline in growth is a reflection of the macroeconomic risks that arise from the sharp decline in output growth among the region’s key trading partners, including China and those in the Euro area. Another factor is the plunge in commodity prices—especially oil, metals and minerals.

Reduced tourism is also playing its part in a handful of African countries, coupled with lower international financing flows and the effects of measures to contain the global pandemic.

A similar set of falling commodity prices and continuing weakness in global growth made Sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP growth decelerate to an estimated 3.0 percent in 2015 from 4.5 percent in 2014.

Such slow pace of growth, which translates into an increase in the region’s GDP per capita of less than 0.5 percent, also occurred in 2009 following the global financial crisis, and contrasts sharply with the robust 6.8 percent average annual GDP growth in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) from 2003-2008

Currently, the countries to which Africa exports the most are also battling the pandemic and trying to mitigate the effects on their economies.

The combination of these factors makes it highly unlikely for African countries to wriggle from the grasp of the looming recession.

In The Event Of No Cases

Till now, Lesotho is yet to register a single case of coronavirus. This raises many questions given than the country is bordered on all sides by South Africa—one of the worst hit in terms of COVID-19 in the continent.

However, if Lesotho’s zero cases are indeed true, it would mean than the pandemic is not hitting its economic activity through the direct channel—that is, the increase in infections and fatalities.

But the WB believes that the virus will impact the Southern African country’s economic activities through a multiplicity of indirect—and international— channels. The first channel is the disruption in trade and value chains, affecting commodity exporters in the region.

The fall in international oil, mineral, and metals has many implications for countries with strong value chain participation, one of which is Lesotho. African countries are highly exposed to changes in prices, due to their undiversified export structures. Oil represents a very high share of total exports.

Copper, as another example, represents 74 percent of the exports of Zambia. On average, the commodities considered in this note represent 48 percent of the exports of each African country.

“The second is the reduced foreign financing flows in the form of lower foreign direct investment (FDI), especially in extractives and infrastructure investments. Foreign aid, remittances and tourism volumes also declining forms part of this second indirect channel,” the Group said.

Indeed, remittances in Lesotho amount to 16 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), according to 2018 data. Most of the country’s remittances come from South Africa, which is not excluded from the contraction in economic activity, especially as it went into recession before coronavirus entered Africa.

Already, the WB has predicted that remittances to low- and middle-income countries would see the sharpest decline in recent history this year, falling by 19.7 percent to around USD 445 Bn, compared to USD 554 Bn in 2019.

In 2019, remittances from African migrants abroad grew by 3.5 percent to total USD 707 Bn. On average, they account for 2.5 percent of the region’s GDP. However, for some smaller countries like Senegal, remittances make up around 10 percent of GDP.

Lockdown Amplifies Effects

Coronavirus will as well find its reactive way into the economic activity of countries, making a path through the disruptions caused by containment and mitigation measures imposed by the government. Even the response of citizens has a role to play.

In this context, this channel exerts a much greater influence in countries with lock-downs relative to those with lesser policies like curfews on none as per “business as usual”. In a general sense, the impact will be in greater folds if the amalgamated effects of knockdowns, infections, international trade plunge and international finance reduction is larger.

According to the WB, the health-related crisis that is taking its toll on the world can be transmitted to the economic activity of the countries where it is happening. This is possible through such nations’ international channels, among other sources of economic development.

Many African countries have responded quickly and decisively to curb the spread of the virus and its potential spike. As the situation evolves there are more questions regarding the suitability and effectiveness of these policies, the chief of which is strict confinement.

The large size of Africa’s informal sector, accounting for 89 percent of the region’s total employment; the precarious nature of most jobs; the limited coverage of pensions and unemployment schemes; and the predominance of SMEs in business all need to be factored in.

These parallels make aggressive containment measures substantially less effective. To reduce the poverty-related effects, the protection of vulnerable groups, ramping up of testing and the promotion of PPE use are better options in such settings.

According to a research by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (2020), attempting to shield vulnerable groups like those over the age of 60 from the virus may be feasible and desirable in low-income country settings. Only a fractional estimation of Africa’s population is over the age of 55. In Nigeria, it is 7.4 percent, and 5.9 percent in the DRC.

The WB says: The capacity to enforce and sustain more aggressive containment measures, like the closure of nonessential businesses, may be far to limited in many African countries”.

Photo by Meritt Thomas via Unsplash