Shock For SafeBoda, Others As Uganda Shifts Goalpost & Chains Bike Transport

A sneak attack on Ugandan bike-hailing?

The Ugandan government got plaudits when it was announced in May that all commercial motorbikes, known as boda-boda, have been advised to register under digital companies with the use of apps like SafeBoda, Uber, and Bolt, or with the authorities. This was part of a ‘COVID-19 control’ plan.

Observers touted the directive as a rare win for regulation-hit ride-hailing in Africa, but it looks like they may have spoken too soon.

Here’s the latest gist: Uganda cleared boda boda to resume operations on Monday, July 28, but the caveat no one saw coming is that they are now banned from accessing most city roads. To put it less nicely, Uganda has banished commercial motorcycles to the suburbs, leaving the city to private cars, bicycles, taxis, and buses.

According to a report, a statement issued by the Kampala Capital City Authority Affairs (KCCA) on Saturday evening shows that the cabinet approved a “Boda Boda-Free Zone” where all commercial motorbikes are prohibited from entering/accessing.

The Boda Boda Free-Zone will run along the following boundaries; Wampewo Roundabout- Jinja Road to Kitgum House junction – Access Road – Mukwano Road to Clock Tower –Kafumbe Mukasa Road –Kisenyi Road –Mackay Road- Kyaggwe Road- Watoto Church-Bombo Road – Wandegeya – Hajji Musa Kasule Road- Mulago roundabout- Kamwokya junction – Sturrock Road – Prince Charles Drive- Lugogo Bypass–Jinja Road- Wampewo Roundabout.

Based on the above, the implication is that the 200,000+ commercial riders in the Ugandan capital, Kampala — out of the estimated 1 million+ riders in the country — are now barred from operating in the Kampala Metropolitan Area with high traffic value and have been relegated to less-trodden paths.

The situation is reminiscent of the now-infamous “Lagos Okada ban” which took effect in February and disrupted many livelihoods, shook bike-hailing startups, and caused difficulties for commuters.

In Uganda, UberBODA and the very popular SafeBoda dominate the bike-hailing segment, and they have made some progress in formalising a ubiquitous but historically problematic mode of transport.

After the pronouncement in May, it seemed like bike-hailing had finally scored a long-awaited win as boda boda riders had been encouraged to sign up on those digital platforms in droves.

But with the latest order banishing boda boda to less profitable zones (whether temporarily or not), it looks like the goalpost has been shifted yet again at “go-time.”

Well, it won’t be the first time. E-hailing companies in Africa seem to always be one regulation away from trouble.

Recent events cast dark cloud around e-hailing in Africa

The e-hailing market in Africa and the Middle East is projected to grow to USD 7.3 Bn by 2023. More specifically, there are estimates that suggest sub-Saharan Africa’s motorbike taxi market could be worth around USD 80 Bn, and in recent times, investors have placed huge bets on startups committed to advancing “Uber-isation” within the sector.

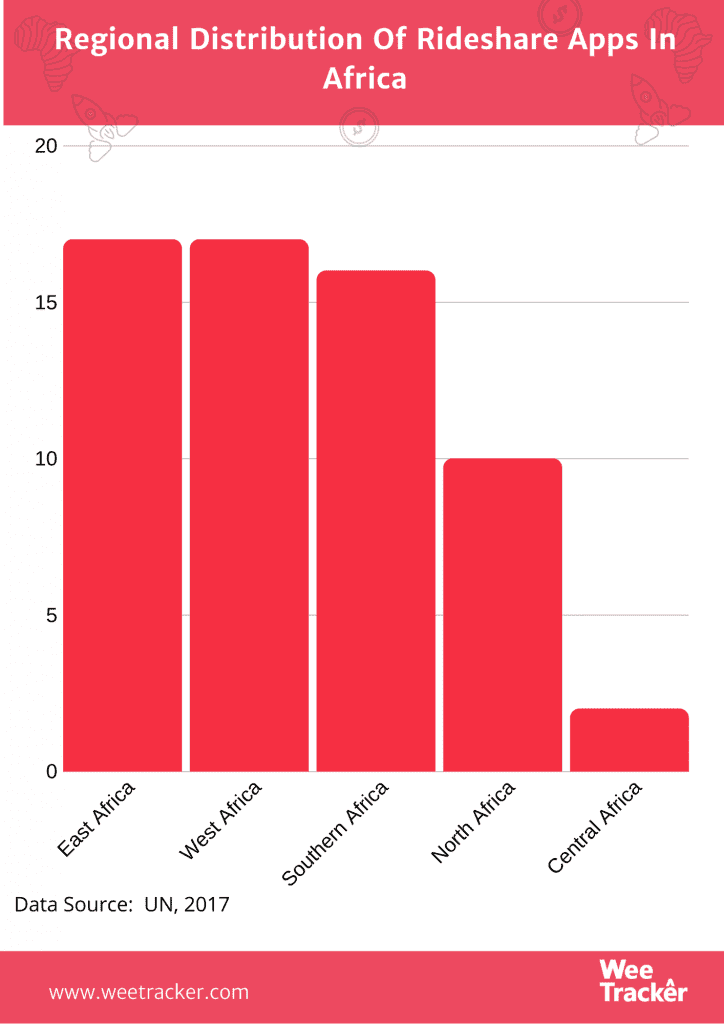

Although up-to-date data on the exact current number of e-hailing companies in Africa is hardly available, some records report 60 e-ride-sharing services across 21 countries as of 2017 (e-ridesharing, in that context, implying real-time ride-hailing and carpooling services).

The key factors driving the demand for ride-hailing services in the region are urbanisation, growing youth population, increasing investments by several major players in ride-hailing services, and a growing number of internet and smartphone users.

Moreover, ease of booking and enhanced passenger comfort offered by ride-hailing services are likely to further propel growth in the African ride-hailing segment for the foreseeable future. But e-hailing companies in Africa seem to be prime targets for distortive attacks.

Last November, SWVL, the bus-hailing startup that started in Egypt, was temporarily banned from Kenyan roads following an order by the National Transport and Safety Authority (NTSA). This was after the government institution claimed that the mass transit company was not duly licensed to operate in the country.

But it wasn’t just SWVL. This fight against what interest groups are calling a “ploy to put the traditional matatus out of business” tanked the bus-hailing unit of Little Cab known as Little Shuttle.

In a renewed fight, the NTSA wrote to the Police this year, asking them to impound SWVL vehicles for operating without proper licensing. This had something to do with SWVL’s choice of routes.

And it didn’t even end there, the NTSA had also requested that the Inspector-General of Police and the Director of Public Prosecutions arrest and prosecute SWVL’s CEO, Mostafa Kandil.

They also demanded that the startup be compelled to cease operations within Nairobi completely on grounds that SWVL has been operating illegally. While the dust appears to have settled since then, it is undeniable that the company is still walking a regulatory tightrope.

In Nigeria, bike-hailing startups saw their market evaporate right before their eyes after the government put an end to commercial motorcycling in key areas of Lagos State in February 2020.

These startups — which had invested heavily in equipment and onboarding riders having raised significant funding from mostly international investors — had been tussling with the government for months over licensing fees and disputed levies. And they got blindsided when the government basically decided to pull the plug altogether.

For cab-hailing platforms like Uber and Bolt, run-ins with Nigerian authorities have become commonplace, as has been the case for those platforms in South Africa. Similarly, both Careem and Uber have had their problems with the authorities in Egypt; problems dating as far back before the two platforms became one.

Featured Image Courtesy: Christian Science Monitor