For Kenyan Fintech Startups, Safaricom Is Both A Blessing And A Curse

If the gist is about Africa’s top brands, then Safaricom is definitely part of the conversation. After all, the listed Kenyan mobile network operator is, in fact, the most valuable firm in East Africa and the 10th largest company in Africa by market cap.

But here’s the gist, though, Safaricom is no regular telco. If anything, it is more. And that “more” part is what makes things somewhat complicated, especially for a class of much smaller and obviously much less powerful companies in Kenya.

Safaricom identifies as a telco but its strides in digital financial services inexcusably position the company as both the nightmare and sweet dream of Kenyan fintech startups, at the same time.

That structural “conflict of interest” sets up a sticky situation; one that perpetually favours Safaricom while advertently or inadvertently stifling fintech startups, especially.

Besides being the leading telecom service provider in the largest and most advanced economy in East and Central Africa, Safaricom is also the feudal lord of Kenya’s fintech fiefdom.

As gatekeeper and fief-in-charge, Safaricom basically holds the keys to fintech innovation in one of Africa’s most recognized fintech ecosystems. And currently, there are hushed concerns from industry players that the telco may be wielding too much power.

Some fear that Safaricom’s grip on Kenyan fintech poses a huge market risk since a whole industry — and one as critical as financial services — is almost completely reliant on a single company.

For startups looking to play in Kenya’s fintech turf, all roads lead to Safaricom, almost inevitably. The telco’s ring is the one fintechs must almost always kiss, not necessarily because they like to, but mostly because they have to.

The company’s hold on Kenyan fintech is aptly summed up by the words of Ali Hussein Kassim, the co-founder/CEO of Kipochi and Kenyan fintech industry expert who also sits on an oversight board:

“If it weren’t for Safaricom, we wouldn’t have any fintech industry to write home about in Kenya. Seriously, M-Pesa provided the first viable ‘rails’ for the fintech industry to blossom,” he said.

Credit to Safaricom, though. After all, it was the telco that laid the foundations for Kenya’s burgeoning fintech sector when it pioneered the widely-popular mobile payments service, M-Pesa, 13 years ago. But now, there are concerns that the bringer of the panacea may have become the problem.

A telco first, or not.

If Kenyan fintech is a stack of 50+ startups focused on payments, lending, savings, investments, advance/overdraft, cross-border remittances, and online payments, Kenya’s biggest telco has claimed a turf on all those terrains.

Indeed, if Safaricom already has the world’s best cake in M-Pesa, then it looks like the company is trying to top that with an icing that is equally mouth-watering.

In recent times, the company has either directly or indirectly layered various products — some of which are the entire business of certain fintech startups — on top of M-Pesa.

In January 2019, Safaricom helped to bring to life an M-Pesa-powered product known as Fuliza in partnership with Commercial Bank of Africa (CBA) and the Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) Group.

Fuliza is an overdraft service that allows M-Pesa users to pay for services when they don’t have money in their M-Pesa account, leaving them with a negative balance until the next time their account is credited. One news report claimed that customers borrowed KES 6.2 Bn (approximately USD 62 Mn) through Fuliza within the first month of its launch.

In November 2012, Safaricom rolled out M-Shwari. It’s a banking product exclusively for M-Pesa users provided in partnership with CBA. M-Shwari provides financial inclusion to millions of Kenyans who previously had no access to micro-savings and micro-credit, straight from their phones.

Additionally, the telco has since enabled the rollout of a product known as KCB M-Pesa in partnership with Kenya’s most attractive bank, KCB Group, as named by Cytonn Investments in its 2019 Banking Sector Report. Just like M-Shwari, KCB M-Pesa provides users with access to savings and credit.

A recent Consumer Sentiments Survey conducted by Boston Consulting Group found that as mobile loans have spiked in Kenya due to the global pandemic, an overwhelming majority of those quick loans (88 percent) have come from M-Shwari, Fuliza, and KCB-M-Pesa — all tied to Safaricom in some way.

Most recently, the company unveiled its very own wealthtech/wealth management platform known as Mali. The latest product is an investment tool designed to allow M-Pesa users to invest fixed amounts, starting from as little as KES 100.00 (USD 0.94), and earn specific returns.

Partnerships with global companies like Paypal, Western Union, and most recently, Visa, have also seen Safaricom plant its foot firmly in the field of cross-border remittances and online payments. As it is, there seems to be some Safaricom-spawn sentry at the gatepost of every fintech segment in Kenya.

The situation has Safaricom either directly competing with startups that have built their entire value proposition on some or all of those offerings, or enabling deep-pocketed legacy financial institutions to challenge early and growth-stage fintech firms.

“Safaricom has a very interesting market position that gives it a unique hold of the fintech space. This is mainly because of the M-Pesa innovation and the market dominance of this service in the mobile money space,” said a spokesperson for one Kenya-based fintech startup who wanted to remain anonymous.

“I wouldn’t term them as being a nightmare, but they have a dual role of being both a significant enabler to fintech and to some degree a direct competitor.”

Big telco, bigger fintech machine?

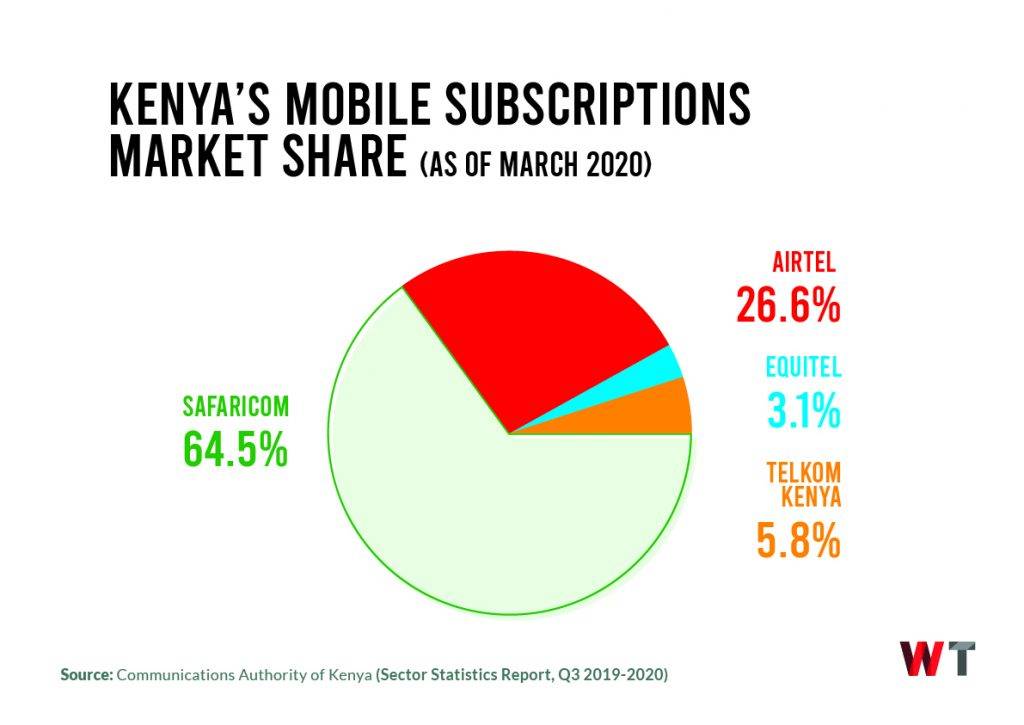

With a subscriber base of approximately 35 million, Safaricom is by far the largest telecommunications provider in Kenya, commanding nearly 65 percent of the country’s telecoms market share. The company’s revenue was KES 251.2 Bn (USD 2.3 Bn) as of March 31, 2020.

However, Safaricom’s efforts transcend telecommunications. Besides mobile telephony, data, and fibre optic services, the company has interests in over-the-top (OTT) services, cloud computing, and even e-commerce.

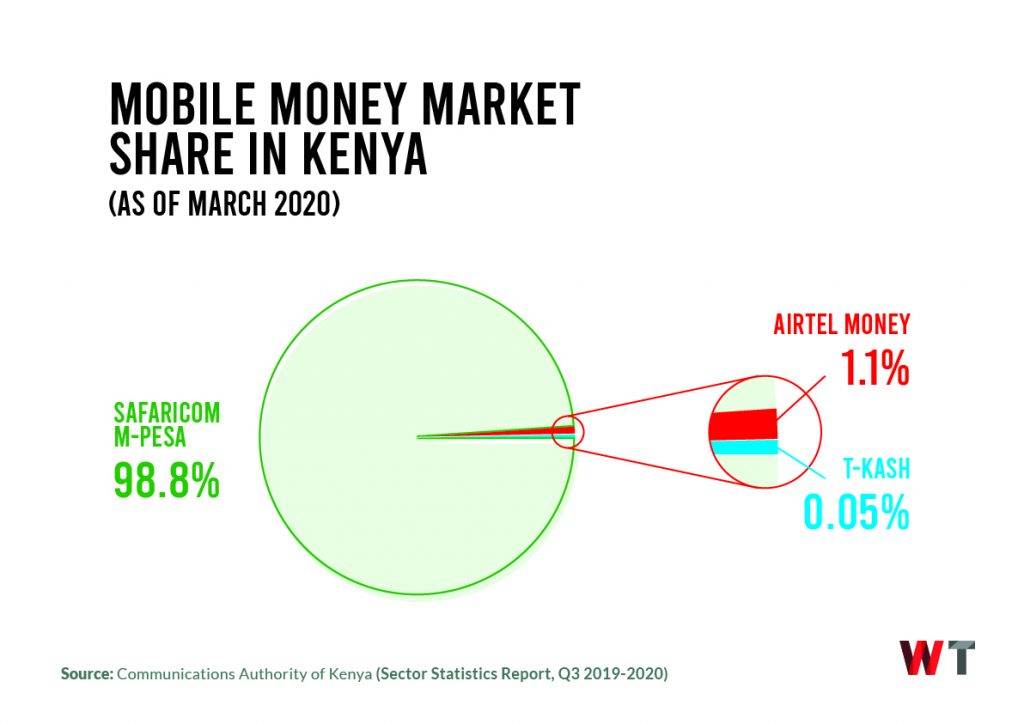

But beyond all that, the telco is most renowned as the birthplace of M-Pesa which facilitates up to 98 percent of all mobile payments in Kenya. No other telco-led mobile money service or digital wallet boasts that kind of dominance in Africa.

Other mobile money platforms in Kenya, including Equitel Money, Airtel Money, Mobile Pay, and T-Kash, all trail M-Pesa by some distance. Both Equitel Money and Mobile Pay have sort of disappeared, as the latest report released by the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) left out both.

M-Pesa is, in fact, the leading mobile money service in Africa, with over 37 million active customers and almost 400,000 active agents operating in a dozen countries in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and Europe.

The service allows users to deposit, withdraw, transfer money, pay for goods and services (Lipa na M-Pesa), access credit, and save funds, all with a mobile device that can even be the most basic of feature phones.

A network of agents comprising airtime resellers and retail outlets acting as banking agents helps with the physical deposits and withdrawals. Users are charged a fee that is not exactly small for using the service.

Generally, mobile money transactions are the most common form of payment in Kenya. Data from the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) show that in 2018, mobile money transactions amounted to KES 3.98 Tn (USD 38.5 Bn); the equivalent of half the country’s GDP.

In 2019, Kenyans moved KES 4.35 Tn through mobile devices. Back in 2014, an astonishing equivalent of 87 percent of the country’s USD 55 Bn GDP passed through M-Pesa. And it is Safaricom that profits the most for facilitating these transactions.

That’s thanks to the telco’s overwhelming haul of 28.8 million users out of Kenya’s 29 million active mobile money users, as well as its near-monopolistic network of 173,000 agents out of Kenya’s 202,000 mobile money agents.

Hence, Safaricom is probably as big a fintech player as it is a telco, if not bigger.

The crux of the matter

Again, credit to the company for the shrewd calls and relentless execution. After all, there’s no rule that says they can’t be as dominant as they are and better at this game than everyone else.

The problem, however, is that the telco may also be suffocating fintech startups as much as it is helping them.

One minute there’s a fintech startup trying to cut it in digital lending (probably by leveraging Safaricom’s infrastructure), and the next minute, they find that the same telco is either directly or indirectly offering the same thing on a larger scale via partnerships with much bigger institutions.

“Fintech in Kenya is synonymous with digital lending, mostly. The ‘Safaricom products’ usually touted as being in direct competition with fintechs are M-Shwari and KCB M-Pesa. These are products owned by commercial banks under special revenue share agreements with Safaricom,” said an executive at a Kenyan lending startup, who didn’t want to be identified.

“Over 90 percent of fintech digital lenders would also not survive without relying on M-Pesa infrastructure to aid their business models. Safaricom still makes money providing this service to the fintech companies. They power the whole ecosystem. They will continuously gain maximum value by being a platform and not providing the services directly.”

The same fintech startup executive, however, noted that recent developments have made M-Pesa seem like a separate business entity from the telco, Safaricom. And the possibility of spinning off M-Pesa into a separate fintech entity and any company decision that withdraws or limits access to M-Pesa is an existential risk for fintechs.

“This is a major development that will potentially see M-Pesa play a more active role in the fintech space. However, going by the historical trajectory, M-Pesa will continue to be a platform for financial institutions to plug into on a revenue share basis,” said the executive.

“It is only if Safaricom shuts access to M-Pesa for fintechs that their existence would truly be threatened. However, it is a huge market risk for a whole industry to be reliant on a single service provider.”

And therein lies the risk; one of a big telco potentially controlling an entire fintech ecosystem; one of dire omens in the event of a system-wide collapse or the malicious compromise of a platform that is so deeply entrenched in Kenya’s economy.

Safaricom’s giant strides in fintech

Here’s some more context: In the third quarter of 2019, Kenya recorded a total of 810.9 million mobile money transactions. Safaricom’s M-Pesa accounted for approximately 81 percent of those transactions, pulling in 655.95 million.

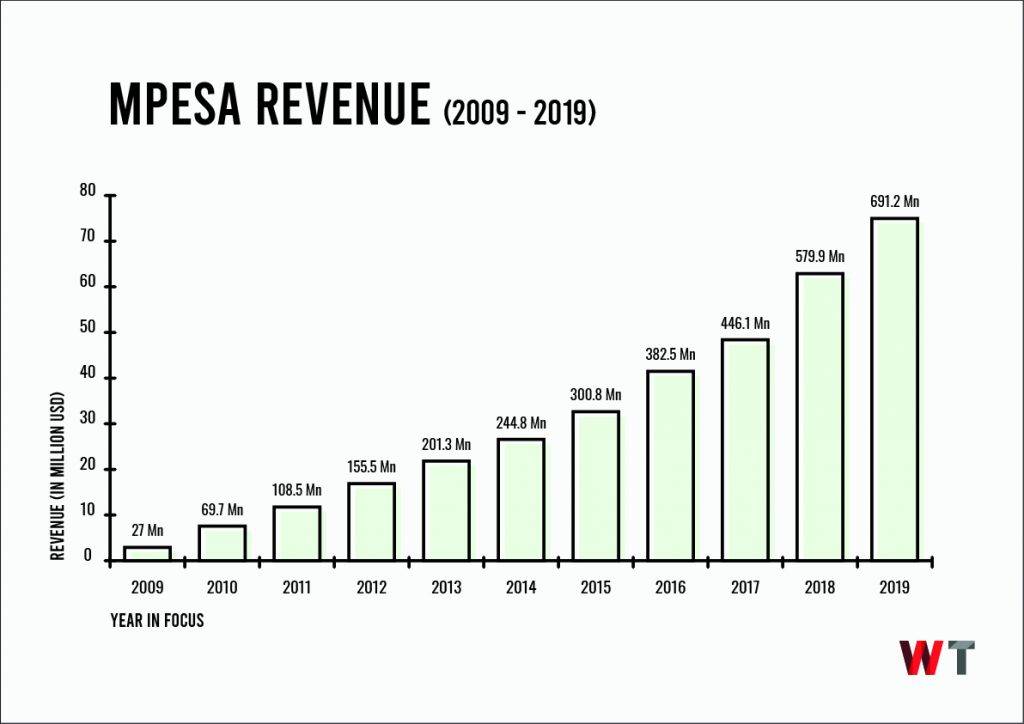

Indeed, in its Full Year 2019/2020 Financial Results, M-Pesa accounted for 33.6 percent of Safaricom’s KES 251.2 Bn (USD 2.3 Bn) revenue. Here, M-Pesa revenues grew from KES 73 Bn (USD 679.3 Mn) to KES 84.44 Bn (USD 793 Mn), posting year-on-year growth of 17.2 percent.

Similarly, in its 2019 Full Year Results Presentation, it was revealed that Safaricom earned KES 240.3 Bn (USD 2.2 Bn) and M-Pesa accounted for 31.2 percent of that sum; that amounts to KES KES 74.9 Bn (USD 691.4 Mn).

As things stand, the mobile money service is the second-biggest contributor to Safaricom’s earnings, just behind “Voice Outgoing.”

By rolling out the all-conquering service that is M-Pesa, the telco helped put Kenya on track to becoming Africa’s top fintech destination, pushing financial inclusion to 83 percent — easily the highest on the continent.

But in M-Pesa, Safaricom also holds the beating heart of Kenyan fintech in its hands, and some industry players are concerned that this can be as much of a problem as it has been a blessing.

While it is undeniable that Safaricom’s M-Pesa provided the habitat for the local fintech industry to blossom, the success and dominance of M-Pesa also put the telco in a unique position in which it has the capacity to play two roles with significant benefits either way.

One of those roles places Safaricom as a huge enabler to fintech; a role the telco has fulfilled with aplomb over the years by opening up its vast infrastructure to fintech companies looking to capture specific market segments.

The other role, however, places the telco as a direct competitor to the same fintech companies, to some degree, whether advertently or inadvertently. It’s like giving out a piece of farmland on a lease and then going ahead to press the lessee for space by cultivating on the same grounds — because the rules allow it.

What’s Safaricom’s game, really?

In July 2015, there were talks of the Kenyan government introducing new regulations in parliament that could lead to the splitting of Safaricom.

Fred Matiang’i, the then-Cabinet Secretary for the Ministry of Information, suggested that this was part of an effort to protect against monopolies.

“Telecommunication firms need to be regulated to ensure some players are not strangled,” he had said. In plain terms, there were concerns that the telco had grown too big and was crushing the competition, unfairly.

It was widely touted that breaking up Safaricom was going to reduce its dominance. This was supposed to be some kind of victory for rivals like Airtel Kenya, which has long argued that Safaricom’s dominance is anti-competitive.

A year prior, the CA had ordered Safaricom to allow its mobile money agents to host services from other operators.

Still, other mobile money platforms like Airtel Money clamoured for the regulation of interoperability costs, lamenting that mobile cash transfers from M-Pesa to Airtel Money attract twice the fee charged on transactions between M-Pesa users. This was labelled an attempt by Safaricom to stifle others in the market.

In early 2017, leaked findings from Analysys Mason (AM); an independent consultant to Kenya’s telecoms regulator, recommended that Safaricom’s voice and data services be separated from its mobile money platform, M-Pesa.

A year later, the same firm sort of abandoned those same recommendations for unclear reasons.

UK-based AM had been contracted in 2016 by the Kenyan regulator to analyse the competitive nature of the local telecommunications market.

In its “revised” report, AM buried its earlier recommendations, saying those measures were “disproportionate” and “constrain” the CA’s discretion to act as they deem fit.

Throughout all these episodes, Safaricom maintained that “it had secured its dominant position by pursuing a sound business strategy and that it was simply unfair for the regulators to seek to punish them for that.”

The company’s position came off as that of the all-conquering tycoon who had a target on their back because of their success. Similarly, when pressed for comments on the company’s fintech efforts and how it might be affecting startups, a Safaricom representative had this to say:

“I think a better story would be to look at the evolution of the entire tech scene rather than Safaricom killing startups.

The company representative further explained, “Look at it this way, banks fought M-Pesa a lot because they saw it as either us or them. Today, M-Pesa makes a lot of money for banks, and it has basically benefited middle-sized and small banks a lot removing the advantage bigger banks had over them by virtue of branch and ATM network.

“When M-Pesa came, there were 4 million bank accounts. Today, there are more than 40 million (registered, not active). What people imagine change will be is very different from what it is,” the company representative said.

Yet even as the storm trailing its competitive practices on the telecommunications front has since passed, there are fintechs that believe its significant strides in fintech is now cause for concern for startups at this point in time.

There’s a bigger threat to Kenyan fintech?

“M-Pesa has done a good job of marketing and creating a large customer base that fintechs can tap into. There is already a market trust element ingrained for any financial service using the M-Pesa platform,” said a top executive at one Kenyan payments startup.

“However, pricing could also be a potential barrier to using their ecosystem platform in the future.”

Hussein, who has a good handle on Kenyan fintech, told WeeTracker that M-Pesa can “be a bit abrasive sometimes” in how it deals with the industry but there has been a significant shift that fuels optimism.

“To be honest, we have seen a marked improvement in their relationship with the fintech ecosystem in the recent past. This can obviously be improved, like any other product and relationship. They are the first mobile money operator to provide an easy-to-use API Platform called Daraja,” he said.

“There are other players that can give M-Pesa serious competition. One is Pesalink, which is owned by the Kenya Bankers Association. Yet banks still find it ‘easier’ to use M-Pesa.”

Bernard Momanyi Nyagaka, co-founder and CEO, Kenya’s Onesha Technologies Ltd; a platform for creatives, is of a similar opinion, stating that Safaricom has recently evolved into more of a collaborator than a cannibal.

“When M-Pesa took centre stage in accelerating Kenya’s future in digital payments, Safaricom seems to have shifted from being a cannibal to supporting the ecosystem in order to build other solutions on top of M-Pesa,” he stated.

Hussein also mentioned that, at the moment, Safaricom, is less of a threat to fintech startups in Kenya than the authorities who make the rules.

“The bigger issue is one of policy and regulation. The sooner this environment becomes easier for fintechs, the better. Policy and regulatory interventions are critical if this sector is to grow,” he emphasized.

As an interesting point, another lending startup in Kenya that sought anonymity echoed Hussein’s words, possibly impassioned by what looks like a government-led attempt to clampdown on the country’s digital lending segment as a whole.

The clampdown on payday lenders may be due to widely-publicised allegations of predatory lending and other dodgy acts that Shylock in William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice would be proud of.

“The biggest threat to Kenyan fintech is traditional thinking and rigid regulators. Their focus should be on facilitating multiple seamless and inexpensive digital payment channels, electronic KYC, and robust digital credit reporting systems,” said the digital lender.

“The ‘expensive’ digital loans that they classify as predatory lending is to a large extent directly correlated to unit economic pricing factoring in M-Pesa costs.”

Surprisingly, this final point is, indeed, a rarely-discussed angle which suggests that the “very expensive” digital lending in Kenya is largely connected to the unavoidable-yet-sizeable expense which startups incur by utilizing Safaricom’s infrastructure.

This brings back a familiar feeling; that of Safaricom being a helpful enabler and a shrewd profiteer at the same time.