Africa’s Murky Space Race: Where Vanity Project Meets Utility Object

The most popular versions of the story behind the early race for space characterises the U.S. and the Soviet Union as sole contenders going head-to-head and trying to outdo each other. But there’s a 1-minute YouTube video that begs to differ.

That video points to the existence of an unlikely third contender, or perhaps, a pretender. The short clip titled: “Zambia’s Forgotten Space Program 1964,” captures the outsized ambitions of an eccentric Zambian school teacher, Edward Mukuka Nkoloso.

He had one big goal: to beat the U.S. and the Soviets in the space race and plant the Zambian flag on the moon. Then, maybe take Mars too.

But Nkoloso went about it in an odd way. He wore a cape, his rocket was a battered open drum, and he accused the U.S. and the Soviets of copying his methods.

That’s besides the fact that his ragtag band of 12 astronauts-in-training prepped for space by rolling downhill in a barrel and learning to walk on their hands, which, according to Nkoloso, was “the only way humans can walk on the moon.”

Of course, that Zambian space conquest never happened, partly due to the fact that Nkoloso — the self-appointed director of Zambia’s national space programme — was never going to be taken seriously, as he pursued those ambitions in a manner that was borderline insane.

Still, Nkoloso’s antics stand as the first of any kind of space endeavour from the African continent, however disappointing. But thankfully, space programmes in Africa have become much more promising and much less theatrical.

Africa’s space race trudges on quietly

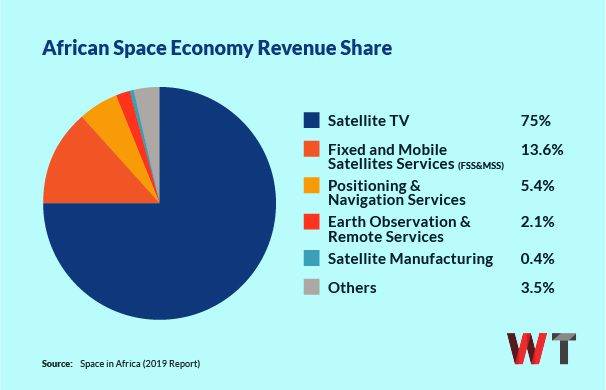

Seeing that Africa’s fledgling space industry currently accounts for a mere 2 percent of the global space economy (valued at USD 350 Bn, according to Morgan Stanley), one might easily lose sight of the tremendous progress made in the last decade or so.

“The African space industry is active and growing, driven mainly by government space programmes, as well as significant commercial interest from within the continent and from foreign operators looking to expand into new markets,” says Joseph U. Ibeh, Senior Analyst at Space in Africa; an organisation positioning itself as the authoritative voice for African space industry research.

Until recently, the nature of Africa’s space industry was a lot like space itself: quiet, dark, and devoid of life. But its history of hushed, sporadic progress seems to have given way to blossoming, enormous growth.

Advances in technology, declining costs of procurement and launch, and rising private/public sector interest have grown Africa’s space industry to one that is worth over USD 7 Bn, according to a Space in Africa study.

The amount stated above encompasses the sum of national budgets for space programs across African countries with space activities and revenue from commercial space ventures. However, it’s merely a drop from the bucket when compared to global figures.

Rania Toukebri, one of Africa’s top aerospace engineers and the Regional Coordinator of Africa for the Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC), notes that Africa’s space industry isn’t quite there yet, though it’s coming together now more than ever.

“The African space sector is in a phase of construction. The African space market is considered raw. compared to others. So there is no surprise of the low production generated,” she tells WT.

“We are still in the phase of building the market and organising the sector. We are unable to follow the speed of the space-faring countries but we can adapt the services to our needs,” Toukebri adds.

But that shouldn’t dull the gloss completely as there’s some traction. According to the 2019 edition of the African Space Industry Annual Report, the industry currently employs over 8,500 people and is projected to grow over 40 percent in the next five years to exceed USD 10 Bn by 2024.

On the other hand, a growing herd of NewSpace startups in Africa has recently become the subject of investor interest, amassing USD 200 Mn in combined valuation, according to Space in Africa. “NewSpace” is the term used to refer to the private sector-led efforts aimed at the commercialisation of space.

Where there is liftoff

Sure, African nations are probably nowhere near putting a man on the moon anytime soon (few countries are that close, anyway), and Nigeria’s bold proclamation of having an astronaut in space by 2030 might seem like the offspring of a tall order and a long shot.

“We are still far from the space-faring countries that are focused on space exploration and creating new technologies for space security,” reckons Toukebri.

“We are certainly not in that phase but we can still start these activities once we gain experience and we cover our priorities.”

Notwithstanding, what African nations lack in space travel, they seem to make up for in other areas of space endeavour.

Yes, contrary to the yearnings of pop culture, there’s more to space science than the landmark development in May 2020, for example, when NASA linked up with SpaceX to launch the first manned flight to the International Space Station (ISS) on a commercially developed U.S. rocket.

Image Credits: aul Martinez/Getty Images

However, space science is not just rocketing. It’s everything from transport, data analytics, data storage, and many more areas of development embedded within the turf loosely described as space science. And in these other areas (besides space travel), Africa’s space programmes are finding their feet.

“Emerging capabilities exist on the continent for the manufacture of small satellites and operations of orbiting satellites of various sizes and missions,” Ibeh tells WT.

“Some African NewSpace companies export vital satellite components and imaging payloads to international clients for various space missions, which accounts for a significant share of the continent’s export earnings in the space industry.”

He further notes that “Africa sees considerable growth in space science and astronomy products and services — primarily driven by demand from government and academic institutions — as a result of increasing multimillion-dollar investments in observatories and telescope projects across the continent.”

Both government-backed and private-owned enterprises in Africa are now making quiet strides in such areas as satellite communications, earth observation, manufacturing and engineering, surveillance services, satellite data and aerospace, propulsion system engineering, and ground station software.

In fact, commercial space companies such as Egypt’s publicly-traded satellite operator, Egyptian Satellite Co (NileSat), Nigeria Communication Satellite Limited (NIGCOMSAT), NewSpace Systems, SCS Space, and Space Advisory Company, are all reported to be generating revenue.

In 2018 alone, NileSat’s revenue was USD 145 Mn, and a recent study identified more than 30 private and public companies doing space work in Africa.

It’s a testament to how the nascent space industry has morphed and evolved. And it’s quite remarkable given that, not too long ago, it wasn’t even much of an industry, to begin with.

Tracking Africa’s space footprints

“Africa started her activities 40-60 years ago. Few countries started creating their space strategies, like South Africa and Egypt,” says Toukebri, who appears to recognise the small, quirky efforts of several decades ago.

However, without considering the earlier-mentioned whimsical campaign in the early years of post-colonial Zambia, Africa’s first real endeavour in space science came in 1999. Twenty-two years have passed since Egypt launched the continent’s first satellite, NileSat-101.

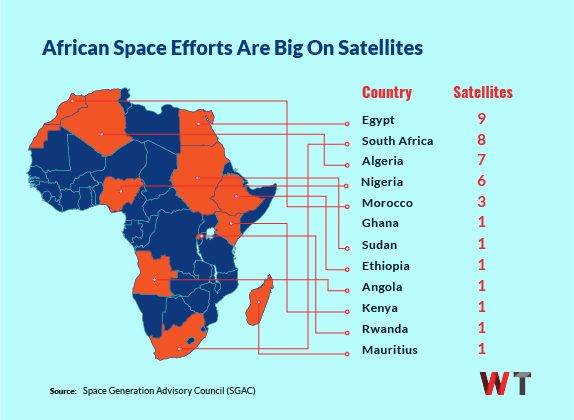

In general, much of Africa’s space journey revolves around satellites — between 1998 to date, no less than 41 satellites were launched into orbit by 12 African countries, according to the Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC).

Of those 41 satellites, 20 were launched in the last four years, signaling a recent spike in satellite engagements, which is the most active space segment on the continent.

As Toukebri explains, “The space projects in Africa are mostly telecommunication satellites and earth observation satellites used for mapping and space services like data processing for the main concerns of each country, the protection of resources, for daily uses and others.”

She adds, “Space in Africa is corresponding to the need of the region. Our efforts are in the direction of bringing space to earth, which means using space services to solve our current issues.”

In terms of utility, Toukebri pointed to the use of satellite data “for military and security of the state, for the protection of resources, for the support of the agriculture sector to make food and water accessible, for disaster management, and for telecommunications and mapping.”

So, maybe it bodes well that Space in Africa projects Africa’s satellite count to more than double to 110 satellites — from the current 41 satellites — by 2024. “We expect that 20 African countries will have launched at least one satellite by 2024, about 81 percent increase,” says Ibeh.

However, most of the completed satellite projects were largely dependent on foreign institutions in the U.S., China, Russia, the U.K., and France.

In fact, only 9 out of those 41 aforementioned satellites were designed, manufactured, and assembled in Africa, and led by African organisations. The rest were partially or fully propped up by foreign entities, with or without contributions from local engineers.

Although South Africa, Egypt, and Algeria boast, by far, the most active space programmes on the continent on current form, it’s hard to miss the government/private-sector-led efforts in Nigeria, Morocco, Ghana, Sudan, Ethiopia, Angola, Kenya, Rwanda, and Mauritius.

But that’s not to say there’s been no collective effort on the continent as a whole, even though no fewer than three such intra-/inter-continental collaborations have failed in the past.

In any case, it’s been 10 years since the African Union (AU) first approved a study to test the feasibility of a Pan-African body for space technology development. This was to be known as the African Space Agency.

Although the idea was put forward in 2010, it took until February 2019 for all the bureaucracy and diplomacy to happen.

And at the 32nd ordinary session of the assembly, Egypt was endorsed as the official host of the headquarters of the AU African Space Agency, to be established in 2023. That’s a full 54 years after the moon landing. But, better late than never, eh?

But the giant space problem remains

Anyway, while some African countries have bought their way into the space conversation by making direct purchases of ready-made satellites from big foreign firms, others have completed small, local space projects through strategic partnerships — albeit stifled by ever-tightening purse strings.

Due to the dearth of substantial local investments, most of the wholly African space projects have had to think small, focusing on the development of tiny stuff, literally — like nanosatellites.

In fact, of the previously mentioned 9 fully African satellites launched to date, all were miniature “CubeSats” except for one, and six of them were launched by South Africa.

It speaks to how the continent’s space industry has always been hampered by a paucity of funds. For context, the U.S. spent USD 28 Bn to put people on the moon, NASA’s 2020 budget is USD 22.6 Bn, and the agency has received USD 650 Bn since inception.

Contrastingly, Africa’s space sector has seen a little over USD 3 Bn in net funding. In addition, Space in Africa estimates that African governments budgeted USD 490 Mn towards their space programmes in 2020, compared to USD 250 Mn in the previous year. The gulf in class is quite obvious.

Of course, it’s hard to compete with a global powerhouse whose GDP is, by itself, nearly 10-times the combined GDP of the entire African continent. And clearly, there are more pressing needs in Africa than “rocket science.” But the numbers speak for themselves still.

Thus, Africa’s space industry continues to be hamstrung by its biggest problem: a shortage of funding, or better still, the difficulty in justifying any sort of demand for aggressive financing.

Why bother about space anyway?

Apart from the recent collaboration between the South African National Space Agency (SANSA) and NASA on a project to explore the moon, Mars, and beyond, South Africa is building the world’s biggest radio telescope, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA).

Image Credits: ESA ALEXANDER

It’s been said that if all goes well, the telescope will enable astronomers to see space like never before.

But this won’t come cheap, the first phase of the project will cost at least USD 790 Mn. And to what end? For some great views of the centre of our galaxy?

That might come off as too much trouble for a bunch of very expensive photographs and misplaced priorities in a country where 49 percent are living in poverty and the unemployment rate is 30 percent.

And therein lies the issue with any form of space technology development in Africa. As it is a continent facing several more-pressing problems at present, forking out huge sums for extraterrestrial espionage is probably not the best way to spend scarcely-available resources.

Africa’s healthcare systems are in need of an overhaul, poverty is a problem on the continent, unemployment is rampant, there’s a huge infrastructure gap, basic education is a challenge, and there are entire national budgets still largely funded by foreign aid and loans.

With problems like those, it’s easy to see why critics have been quick to dismiss the space pursuits of African governments as a vanity project at best and a corruption scheme at worst. Why bother with outer space when inner space desperately needs fixing?

This also captures why Africa’s space scene sees lukewarm activity, even though advances in space science does have ties to broader economic development.

For instance, Toukebri believes space services and products will be able to improve security, boost internet services, improve access to water and food, protect resources, and much more.

Indeed, the space industry does align with the objectives of the African continent for smart, sustainable growth.

“Space science and technology are integral foundations of most modern technologies ranging from mobility to automated teller machines (ATMs), internet connectivity, agricultural extension services, etc.,” Ibeh explains.

“In Africa, satellite broadband is helping to provide connectivity to remote areas where terrestrial infrastructure is unable to reach. With satellite connectivity in rural areas, anyone can layer essential applications that deliver educational content, telemedicine services, digital payments, and agricultural extension services,” he notes.

Space science might seem like a very niche, esoteric subject. But it’s a known catalyst for growth and opportunity-creation in other familiar areas like telecommunications and agriculture, as well as in lesser-known areas like navigation and earth observation.

In Nigeria and Ethiopia, for instance, space projects have birthed satellites that are already supporting development efforts through weather monitoring, climate data collection, tracking down security threats in conflict zones, and aiding disaster planning.

These efforts can prop up independence and security, while also helping to tackle major societal challenges including food shortage, climate change, drought, urban sustainability, and the many other “more pressing” issues that currently outrank space science on the priority list.

But to get that sort of liftoff, there’s a need for some major thrust.