The Nitty-Gritty Of Nigeria’s Twitter Ban And How Deep It Can Go

In the face of heightened insecurity, banditry, terrorism, kidnappings, arson, and sporadic outbreaks of violent attacks across the country – coupled with the well-documented corruption, unemployment, inflation, and general economic decline – Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari thought to speak to the nation.

His speech could have been empathetic and reassuring but it mostly came off as threatening. And as if it wasn’t bad enough that it was televised, that speech found its way to the President’s Twitter handle.

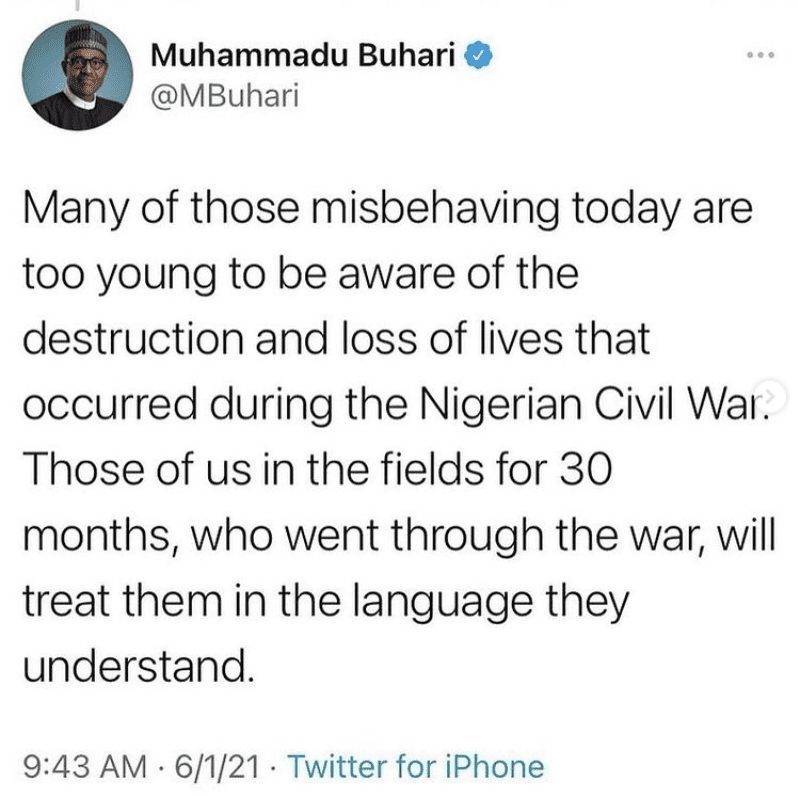

“Many of those misbehaving today are too young to be aware of the destruction and loss of lives that occurred during the Nigerian Civil War,” a part of the now-deleted tweet read.

“Those of us in the fields for 30 months, who went through the war, will treat them in the language they understand.”

That statement is an allusion to the Nigerian Civil War which lasted for 3 years starting from 1967 and led to 2-3 million deaths, mostly among people of the Igbo ethnic group in Nigeria. President Buhari had said those very words on TV and opted to reinforce the statement by tweeting it.

But Nigeria is Nigeria, and Twitter is Twitter. Last year, the micro-blogging and social networking platform headed by CEO, Jack Dorsey, didn’t shy away from reining in then-US President Donald Trump when his insidious tweets became very dangerous.

So, in the same fashion, Twitter deleted President Buhari’s insensitive tweets on Wednesday, June 2, 2020 – a day after the tweet was sent out. The company said, “the tweet violated the Twitter Rules.”

Shortly after, a member of President Buhari’s cabinet swung into action, scheduling a hastily put-together press conference that ostensibly happened quicker than the government reacts to more-pressing issues like violent attacks and mass kidnappings of schoolchildren.

In the press conference, Lai Mohammed, Nigeria’s Minister of Information and Culture, said “Twitter’s mission in Nigeria is suspect.” Twenty-four hours later (on Friday, June 4), it was announced that the Nigerian government was suspending Twitter’s operation in the country indefinitely. And it’s quite ironic that the suspension also had to be announced with a tweet on Twitter.

Lai announced the suspension in a statement issued in Abuja on Friday, “citing the persistent use of the platform for activities that are capable of undermining Nigeria’s corporate existence.”

The Minister said the Federal Government has also directed the National Broadcasting Commission (NBC) to “immediately commence the process of licensing all over-the-top (OTT) and social media operations in Nigeria.”

It may not have surprised many given that the Buhari administration has time and again demonstrated a propensity for human right infringements and violations, and displayed a renewed appetite for muzzling ever since Nigerians took to the streets and to social media to protest police brutality and poor governance last year. But the announcement of the suspension of Twitter – a platform that upholds responsible free speech – was no less shocking.

For much of Friday evening, Twitter remained accessible in Nigeria. But come Saturday morning, Nigerians found they couldn’t access Twitter as they normally do. As of this moment, Nigeria has cut off Twitter, blocking a platform that has 17 million users in the country – including a litany of government agencies.

At this time, the Twitter app and web platforms are inaccessible from Nigeria, though locals are exploiting the route provided by virtual private networks (VPNs) to stay tweeting. For users who can’t use a VPN for some reason, Twitter is unavailable.

On its part, Twitter itself says it is “deeply concerned” by the action taken by the Nigerian government.

How could this have happened?

China, Iran, North Korea, Egypt, and Turkmenistan. These are other countries where Twitter, specifically, is currently or previously blocked. When it comes to general internet shutdowns/restrictions or periodic social media blackouts, several other African countries like Uganda, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Togo, Burundi, Chad, Mali, Guinea, etc., are all in that category.

While Nigeria has never recorded some form of restricted access to the internet or social media applications before now, it has now joined an infamous group of countries that have blocked Twitter specifically.

And it says a lot that all the countries mentioned above are at the bottom end of rankings that study press freedom, free speech, and freedom of information. But that’s by the way. Now, how does the whole “let’s block Twitter” thing work? How come Nigerians went to bed using Twitter and woke up unable to use it?

Turns out it’s quite easy, especially for a government that likes to throw its weight about in an effort to silence dissent. A government can restrict access by ordering internet service providers (ISPs) to limit access to their subscribers.

In fact, the Association of Licensed Telecommunication Operators of Nigeria (ALTON), the official industry body for all providers of telecommunications services in Nigeria, has just confirmed that its members received formal instructions from the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), the country’s industry regulator, to suspend access to Twitter.

NetBlocks metrics confirm the restriction of Twitter in Nigeria from the morning of Saturday, 5th June 2021. Network data show that access to the Twitter platform and backend servers is now restricted on leading networks MTN, Globacom, Airtel, and 9mobile.

To understand how this works, it helps to think of internet providers using this analogy on NPR: Imagine calling an operator and saying, “I want to talk to my friend Twitter.” You don’t know Twitter’s phone number, but the operator can look it up in the phonebook and connect you. Your internet company is essentially your operator on the internet.

When a person types Twitter.com into their browser and “Enter”, their computer talks to their internet service provider’s servers (MTN, Airtel, Glo, Spectranet as the case may be in Nigeria). The ISP’s servers then use the Domain Name System (DNS) to lookup Twitter’s servers’ IP address. The ISP’s servers direct the person’s request to Twitter’s servers, wherever in the world those servers may be sitting.

So when a country’s government decides to block locals from accessing Twitter or any site for that matter, they essentially compel the network operators (ISPs) to erase Twitter’s listing in the Internet “phonebook.” That way, Twitter.com won’t connect to anything — but the site is still very much accessible in other ways.

That’s where VPNs come in

In more cordoned-off countries such as China, the internet borders are very secure and tight. There, the government has the capacity to filter web traffic at almost every physical pathway into the country.

However, in a country like Nigeria where the internet infrastructure is codependent on the infrastructure that runs through various other countries, there are loopholes that can be exploited with ease.

It follows that people in Nigeria can still access Twitter or any other sites on the government’s blacklist as long as they don’t use their Nigerian internet provider’s DNS servers.

In other words, one can use a VPN or proxy server to tunnel their internet connection outside of the country, and there are tonnes of these sorts of tools on the internet. These days, it’s as easy as downloading some app or some extension and tapping the “ON” button on the app.

And, apparently, Nigerians are already getting acquainted with VPN life. In fact, Google Trends suggest VPN searches in Nigeria have surged 14-times within the first 14 hours of the Twitter ban.

But there are no silver bullets

Sure, VPNs are helping Nigerians stay on Twitter but this may just be the start of more problems. For one, the Nigerian government has revealed its intention to stifle OTT and social media platforms in general.

So, the likes of Facebook (which also took down the controversial speech on President Buhari’s page yesterday), WhatsApp, YouTube, Telegram, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, Netflix, etc., are not exactly home and dry.

A renewed and intensified effort by the Nigerian government to stifle social media would probably entail similar restrictive actions taken against the other platforms in the country.

In 2020, the number of social media users in Nigeria reached roughly 28 million. As of the third quarter of 2020, WhatsApp was the most popular social media in Nigeria. The platform was used by 93 percent of internet users aged 16 to 64 years, according to Statista.

Facebook and Youtube followed, being used respectively by 86 percent and 82 percent of the individuals with access to the internet. Also, of the 28 million social media users in Nigeria, 61.4 percent are Twitter users.

In Nigeria, social media serves as a backbone for commerce, crowdfunding, missing persons and emergency response initiatives, accountability, and even governance. A social media blackout, thus, has far-reaching implications.

One might argue that VPNs offer a way out but they are merely a stopgap and certainly not the ultimate solution. In fact, a government that is determined to stifle access to OTT and social media platforms can realistically make VPNs powerless and useless.

There exists a well-known technique called VPN blocking. It is used to block the encrypted protocol tunneling communications methods used by virtual private network (VPN) systems. It is often used by large organisations such as national governments or corporations and can prevent the use of VPNs to bypass network firewall systems.

Simply put, VPNs can be effectively blocked and, indeed, countries like China, Russia, Iran, Syria, Pakistan, etc., are known to have implemented VPN blocking efforts in the past with relative success. Alongside VPN blocking, there have also been cases of arrests and punishment of individuals who persist with the use of VPNs in those countries.

As it is, there’s nothing stopping this unfolding digital war from going that deep in Nigeria.

Featured Image Courtesy: New Indian Express