Tech Alone Is Unfit To Fix African Pharma, Now What?

About three years ago, South Africa launched what most of the world validated as a brilliant idea. As more people in the country complained of prolonged wait times at pharmaceutical centers, the country unveiled a cutting-edge network of pharmacy dispensing units (PDUs), commonly called ATM pharmacies.

These remote pharmaceutical units were a great initiative, one that came as sweet convenience to South Africans battling chronic illnesses, majorly HIV, tuberculosis and diabetes. Each of the PDUs, which cost about USD 159 K, are ATM-like units that not only dispense medications but also allow patients to discuss their challenges with pharmacists via a Skype-like interface.

The overarching aim behind introducing PDUs was “bringing healthcare closer to the people”, down to the last mile. This too has been the mantra driving the tech-driven endeavor to revolutionize the healthcare industry across Africa, a race that has since gone in various directions, pushing the industry into the venture capital mainstream.

It is difficult to ascertain whether or not healthtech has had a substantial impact in Africa, since most companies in the space are yet in their earliest stages. Besides, the continent has one of the world’s most fragmented healthcare systems, and everything from regulation to enablement is close to nonexistent for healthtech startups.

In our previous coverage on healthtech, Chibuzo Opara, Founder and CEO of Nigeria’s DrugStoc, opined that tech is all but enough to address the pitfalls in the fragmented African pharmaceutical industry, one bedevilled by fake and substandard medicine. His reason? Majorly the lack of healthcare financing, particularly towards improving the industry’s supply chains.

Samuel Okwuada, Founder and CEO of Y Combinator-backed Remedial Health, a Nigerian healthtech fresh out of a seed capital injection of USD 4.4 M, similarly opines that tech is quite limited when it comes to bringing primary [and affordable] healthcare closer to the masses.

Courtesy: Remedial Health

In this exclusive interview with WeeTracker, Samuel additionally asserts that patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs)—much unlike clinics and hospitals—form the significantly overlooked market segment in African healthcare and healthtech, most likely the reason for the staggered uptake of digital health services in the continent.

Thanks to increased investments in African healthtech, innovation appears to be [finally] reaching the last mile.

For all we know in healthtech here, it is mostly about hospitals, pharmacies, clinics, and consumers on the brink of tech-driven disruption. How do PPMVs come into the mix?

Samuel: The one problem I highlight with most founders today is that we are already accustomed to looking at how tech can be used to revolutionize an African industry, forgetting that we are not a very rich continent.

Let me use Dangote as an example; he is the wealthiest man in the continent because he has been able to provide essential commodities that even the bottom 1 percent will need. Hold that thought.

When we first looked at the healthcare market, the first best thing to consider was Pharmacy, majorly because I am a pharmacist by profession. PPMVs are usually small medicine stores limited in the range of products they can sell and usually do not have an in-house pharmacist.

In most parts of present day Nigeria, PPMVs are called “chemists,” although the term has different contextual meanings.

Also, in most cases, those in charge of these PPMVs are, more often than not, uneducated. While some have secondary school certificates, most of them are not literate. This makes the PPMVs a harder nut to crack. But, despite being the more challenging market to reach, 80 to 85 percent of the medicines in Nigeria are distributed through them.

The ratio of pharmacies to PPMVs in Nigeria is, as of the last available data, quite troublesome. The country has just 10,000 pharmacies, which is barely enough for a population of 160 million, going to 200 million. Meanwhile, there are over 250,000 PPMVs in the country.

For anyone looking at the market, [yes] the pharmacies and the pharmacists are the easy places and people to go to. It is easier to explain to them the issue of drug counterfeiting, thanks to professional training on how to look after patient health.

The PPMVs are also looking after patients’ health, but a good number of them are profit-driven small businesses. Some of these enterprises do care about the substantial medicine problem, and most of them are indifferent—as long as they make money.

If you want to distribute pharmaceutical products to the population, it only makes sense to target the PPMVs. This is because they are not only more in number than pharmacies but are also easier to access, especially in ruralities and remote areas.

For most Nigerians, PPMVs are usually an average of 15 minutes away from wherever is their current location. In a place like Oshodi—often referred to as the center of Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial hub—there are over a hundred of them. They are not on the high street, do not have signages, and one might need directions to locate them. Regardless, PPMVs are often 15 minutes away.

We have been talking about the low count of pharmacies. However, when it comes to hospitals and clinics, things are even worse. Hospitals and clinics combined, there are only 3,000 to 5,000 of them in Nigeria, which trickles down to 1 doctor to about 10,000 people.

At the government level, this problem has not been tackled; we are just sitting on a keg of gunpowder and waiting on what might happen next. The way we see it is: why not leverage PPMVs to deliver primary healthcare to the common person? How about some doctor or diagnostics services, too?

Back to what I said at the beginning. As much as we think of using tech, we need to consider the nature of the African population. In the telemedicine sector, for example, there are many loopholes. Not all everyday consumers have smartphones, not all of them are tech-savvy, and not all of them can afford the subscription services on offer.

How about delivering telemedical services via nearby PPMVs and pharmacies instantly? That is how we are looking at it. It is a way to provide more access to patients and enable these businesses to make even more money.

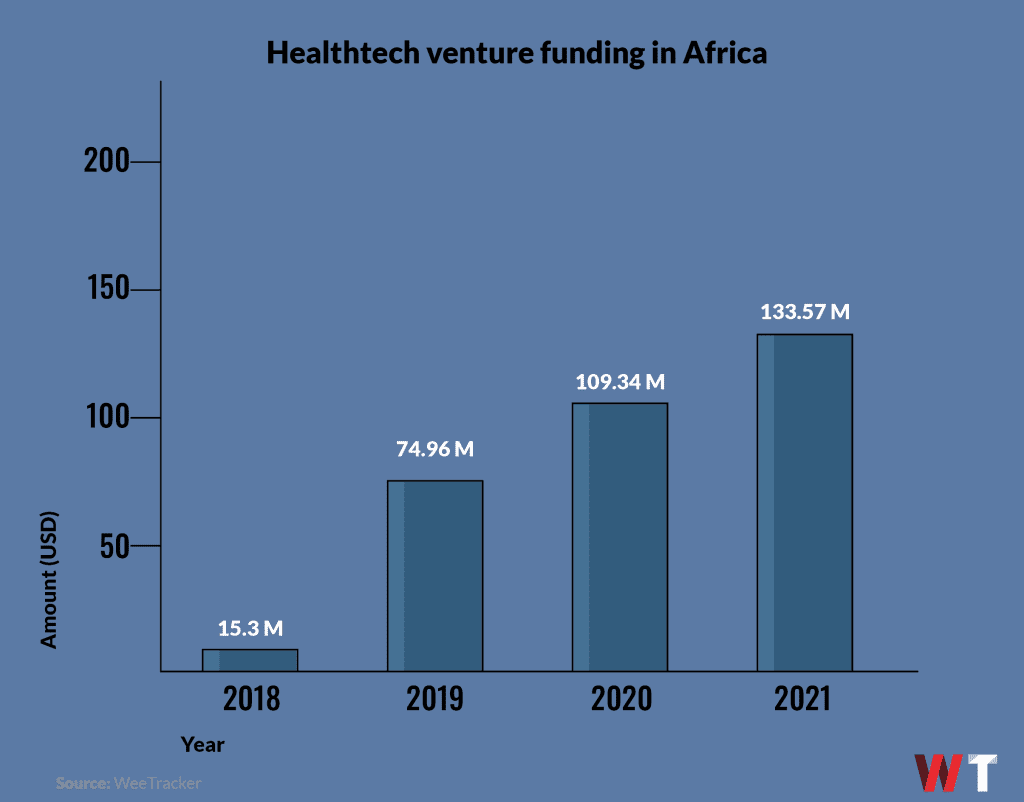

Per WeeTracker’s investment report for 2021, healthtech was the fifth most funded sector in African tech. Early into 2022, deals are piling up, so do you think investors will be bullish?

Samuel: Definitely, investors will increase their commitments to African healthtech going forward. I believe so for many reasons.

Firstly, financial services is a massive industry in Africa, and needed a lot of innovation. But, I think the fintech boom has peaked, as some of the solutions on the rollout nowadays are somewhat identical, however needed—considering our population. The way we see it is that the next market that is anything as big as that of financial services, is healthcare.

Secondly, African healthcare has been substantially ignored by the government, for the longest time possible. If the pandemic taught us anything, it was that the NGOs and foreign aids we depended on would focus on their own countries and citizens when push comes to shove [as it should be].

A lot of investment has to enter the sector to take care of our expanding population. Last I checked, the Nigerian population alone is expected to grow to 400 million people by 2050. Who is going to take care of these people healthwise?

At the moment, it is a struggle, and with the current talent drain in the country, things are getting worse by the day. Basically, Nigeria is training doctors for the benefit of other economies.

What will happen to African healthcare in the next twenty to thirty years? If private investors can come into the market, we can do what was done in telecommunications and financial services—developing without the government.

We talked specifically about the Nigerian market. Does the PPMV potential exist across Africa? If yes, does that mean no one has since been “digitizing” the market?

Samuel: Yes, the model we have been operating in the Nigerian market can be successfully replicated across the continent. I would say, South Africa, Egypt, Kenya, and Nigeria are the top four markets where PPMVs are the chief enablers of medicine flow. In some cases, they circulate as much as 95 percent of drugs.

Secondly, it is not that no one has attempted to digitize the market. Plus, when you say “digitize,” are you providing software to improve healthcare operations or just bringing practitioners and patients online?

Different people have tried various things, but most of the focus has been on pharmacies. The reason is simple: the typical pharmacy is probably on the high street where it is easily spotted, most likely has a resident pharmacist, has some kind of power supply, and has a reasonable level of computer literacy. These established, you can offer solutions they can quickly adopt.

When you go to the PPMVs, it is an entirely different situation. Last week, I visited one who has not had power for three to four months. Because the PPMV does not generate enough income, the business could not afford a generating set. Still, customers come to buy, even at night, when they make do with rechargeable lanterns and smartphone flashlights.

It makes no sense for us to think of digitizing such a business because adoption would be slow and stunted. That is why PPMVs in Nigeria [and Africa] have been largely ignored. Because they are at the bottom of the pyramid and a mass-market, one would spend tons of money pulling complete digitization off.

Digitization is gradual. First, can you enable them to order medicines quickly, without moving a muscle? In a market like Africa, tech companies have to come down to this level and upgrade the market by creating an avenue for their customers to easily keep their stores stocked with products.

Can you deliver them on time, offer a BNPL option, enable them to fight substandard drugs, and help them keep their kiosks running?

Those are the questions we ought to ask ourselves.

It appears that drugs are very expensive or overpriced in these markets. Why is that so? Meanwhile, where does buy-now-pay-later come in? Remedial Health appears to be big on pay-later services.

Samuel: Yes, drugs are primarily overpriced in this market.

Now, we are sort of simultaneously tackling multiple problems: drug counterfeiting, inaccessible healthcare, medicine mishandling, and poor drug storage.

Even when you go to those markets to purchase some medicine for your shelf, a regular pharmacy will have a thousand SKUs in stock. To buy them, you will probably need to talk to more than thirty people in the market, which means you will have to work with thirty different distributors.

That is an entire day’s job. In some cases, you need sales representatives from pharmaceutical companies to visit a physical client store before they can sell [send] all the required medicine over.

We also know that, in Nigeria and across Africa, access to credit is another huge problem. 80 to 90 percent of [small] businesses in the continent cannot access credit via banks or other financial institutions. How can such a business grow? That’s where buy-now-pay-later comes in. Our BNPL service is, for now, provided to the PPMVs and pharmacies because we are a B2B business.

In terms of product costs [a typical medicine distributor does not work with up to ten pharmaceutical companies at a time so], buying in parcels from distributors does not make sense because they buy in bulk, looking to dispose and make money quickly. At the end of the day, the market has different tiers of distributors, sometimes up to ten.

Usually, pharmacists and PPMVs buy from tier-three distributors, who—wanting to make money—might sell at higher prices. Before the drugs get to the PPMVs and pharmacists, the costs can appreciate by 30 to 40 percent.

The patients might end up buying these medicines at 50 percent more than the usual price. The price of drugs from global brands can increase by 150 percent within this supply chain.

What challenges are associated with digitizing PPMV and pharmacist operations in Nigeria and perhaps across the continent?

Samuel: I would not say those challenges are unique to us, as they come from the general climate above tech startupping in Africa.

There is the logistics problem; moving products from place to place is no walk in the park, not just promptly, but also cost-efficiently. The purpose of healthtech is to reduce the existing barriers and lower costs. Logistics is a salient part of this.

As much as smartphones are virtually everywhere on the continent, not many people are very tech-savvy, at least not yet. So there is often a lot of training and retraining needed to enable the market to readily adopt the proposed technology.

The eCommerce sector in Africa is moving, but not a lot of people are trusting of buying stuff online [yet], which means that the market is still growing.

In the same way, when pharmacists and PPMVs come on, some of them might be on the lookout for outrageous profits in a short period of time. Along this growth curve, we teach the value of patience.

It is all a matter of time because everything will [definitely] be improved. For example, when I was building an eCommerce firm way back in the day, I saw first-hand how much of an ordeal it is to get retailers in Lagos’ Computer Village to sell their items online. But, JUMIA and Konga came around, and having spent some money on this cause, selling online is now a norm for Computer Village.

It is a process. It will take some time. But it will eventually happen. It has to.

This publication has been update to reflect Remedial Health’s most recent venture funding round.