DropX Shutdown Reflects Harsh Realities Of Nigeria’s E-Logistics Terrain

On-demand logistics startup, DropX, the self-described “Uber for delivery” that took off in Abuja, the Nigerian capital, is shutting down.

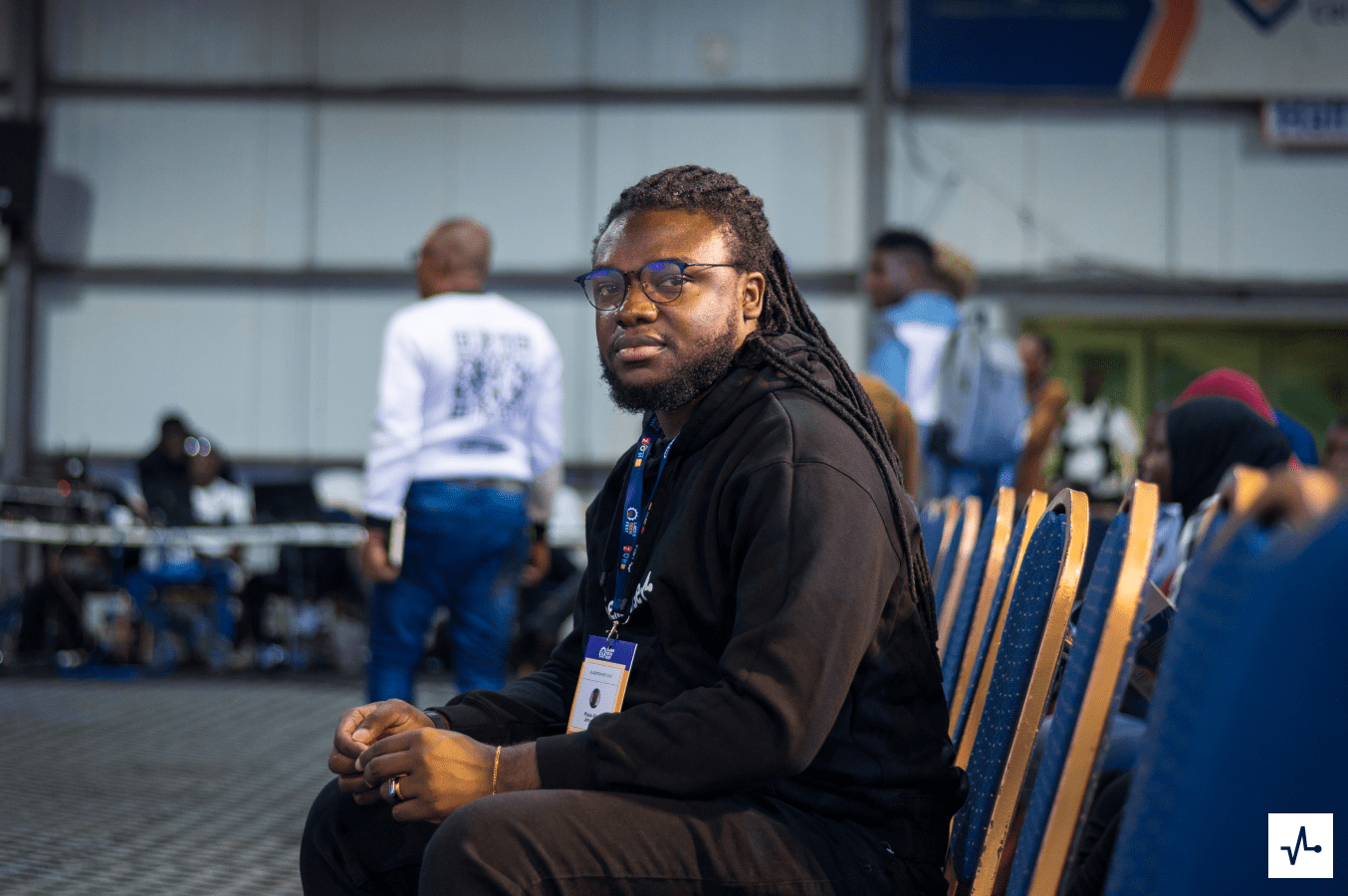

In a LinkedIn post that echoed the struggles of many startups in Nigeria’s bustling tech scene, Praise Alli-Johnson, co-founder of DropX, announced the closure of the hyperlocal delivery service. The post-mortem peeled back the curtain on a venture that began with promise but succumbed to the unyielding challenges of the e-logistics sector in Nigeria.

Founded in 2021 by Alli-Johnson and Oluwatope Liasu, DropX entered the scene with ambitious goals—to transform local deliveries in Abuja by connecting businesses and individuals with swift, reliable services. The concept garnered early traction, onboarding 2,000 users enticed by free initial deliveries and enlisting 500 drivers, predominantly car owners already engaged in the gig economy via ride-hailing platforms.

However, the initial success faded into a blizzard of obstacles. The delicate balancing act between driver earnings and user affordability proved to be a recurring stumbling block, causing the business to suffer negative unit economics resulting in the founders having to fund the difference out of pocket to keep orders going. Despite efforts to cater to high-value clientele seeking premium services, revenue growth remained elusive.

The inherent complexity of Abuja’s geography posed another obstacle. The dream of hyperlocal delivery clashed with the reality of scattered user locations across the city, hindering efficient service outside specific areas. Despite concerted efforts to consolidate users in targeted zones, the disparity persisted.

As demand surged, the company found itself entangled in fierce competition for driver availability and pricing, battling other ride-hailing platforms. Attempts to emulate surge pricing models faced user backlash, highlighting the delicate balance between demand and service quality.

The pursuit of a diverse fleet, integrating bikes alongside cars, aimed to address user needs. However, this diversification inadvertently exacerbated the challenge. Users favoured cheaper bike deliveries, disrupting the dynamics and leaving high-value clients dissatisfied.

The quest for scalable solutions led DropX to explore partnerships with bike suppliers like TVS. Yet, government policies banning specific bike models derailed these plans, forcing a retreat. Moreover, human factors, including off-app transactions and user behaviour, added to the company’s woes.

Subsequent efforts to partner with the national courier, the Nigerian Postal Service (NIPOST), also fell through. Financial strains mounted, and the founders found themselves effectively funding deliveries from their salaries in the final months until the decision to pull the plug on the venture.

The closure of DropX joins recent shutdowns of delivery services like Jumia Food and Bolt Food, underscoring the uphill battle faced by e-logistics ventures in Nigeria. Economic constraints, wafer-thin margins, fierce competition, and infrastructural inadequacies pose hurdles for businesses in this space.

Reflecting on the bumpy journey, Alli-Johnson shared insights into the pivotal choices made and the lessons learned. The absence of Product-Market Fit (PMF) dissuaded DropX’s leadership from raising external funding and their reluctance to perpetuate the sunk-cost fallacy led to a candid acknowledgement of the venture’s limitations, Alli-Johnson volunteered.

“We believed we hadn’t achieved PMF. We couldn’t keep burning cash and add someone else’s cash to the fire. We thought that once we could stop covering delivery cost differences and account for at least a 10% cut in delivery fees, we could claim PMF,” he writes. “I strongly believe VC funds are for growth after stabilising. If I were a VC, I won’t[sic] give us money at the stage we were in.”

Alli-Johnson also added, “The concept of hyperlocal delivery on demand sounds great, but it demands more than just a great app and technology. All the fancy route optimisation and device tracking can’t overcome actual human factors and infrastructure deficits. I’d say we got tired; as the user base grew, so did our spending on nearly every delivery. That’s nothing to smile about.”

Yet, despite the disappointment, both co-founders chart new paths. Tope ventured into business development, leveraging her expertise from previous roles, while Praise turned to supporting startups, drawing from the crucible of experiences at DropX.

What could have been done differently? Maybe not started at all, Alli-Johnson quips humorously for starters.

“Perhaps run as a traditional delivery company supported by a fancy app for order receiving and tracking, but where’s the fun in that? (We’ve done that before.) Maybe pushed the NIPOST collaboration better, but elections change everything, and a 4-year plan isn’t ideal. Or maybe raised a large sum of money for a massive onboarding blitz, fixing the chicken-and-egg problem in one go. Maybe, just maybe?!,” he adds.

As co-founders Johnson and Liasu chart new paths, their story sheds light on the daunting realities confronting startups in Nigeria’s e-logistics arena. The task of revolutionising e-logistics remains elusive, demanding resilience, adaptability, and a pragmatic approach to innovation.