A Rare Win Is Coming For Regulation-Hit Ride-Hailing In Africa

e-Hailing vs Regulation

Regulations are supposed to cut both ways but when it comes to transport regulation in Africa, e-hailing firms would be quick to state that it has been a single-edged sword. One that seems to always have them on the injurious side.

Across Africa’s largest markets and tech hubs — from Nigeria to South Africa and even Kenya and Egypt — e-hailing firms, which exist to fill the ever-widening gaps in the transport sector, have time and again been reminded that theirs is a thankless job. In fact, they seem to always be one new government regulation away from obscurity.

The e-hailing market in Africa and the Middle East is projected to grow to USD 7.3 Bn by 2023. More specifically, there are estimates that suggest sub-Saharan Africa’s motorbike taxi market could be worth around USD 80 Bn, and in recent times, investors have placed huge bets on startups committed to advancing “Uber-isation” within the sector.

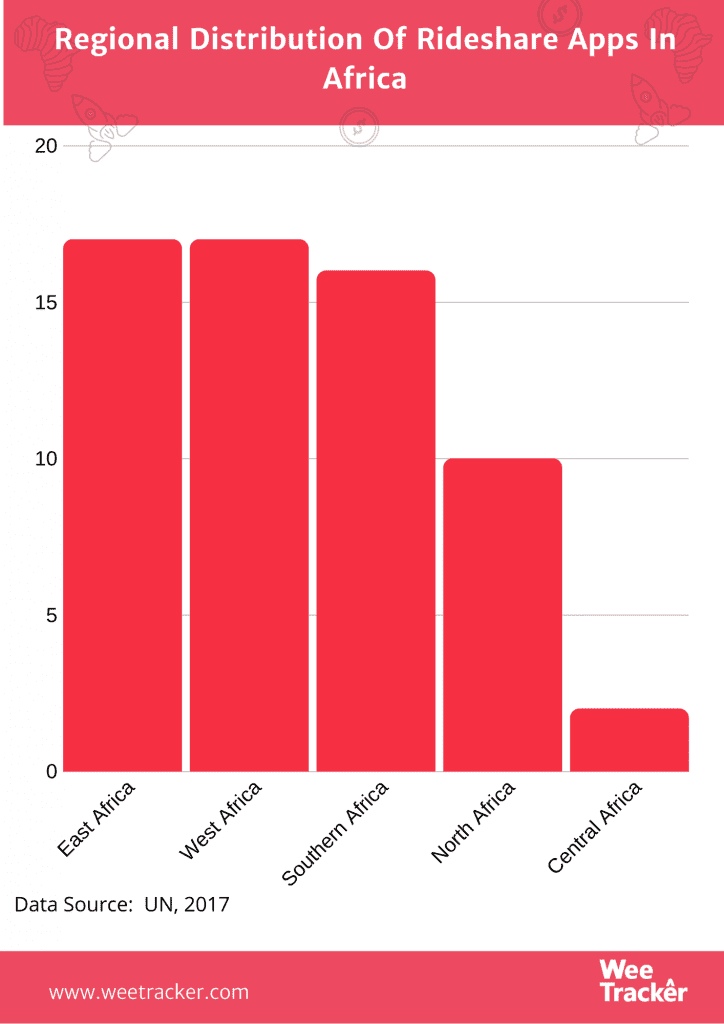

Although data on the exact current number of e-hailing companies in Africa is not readily-available, TechCabal reported 56 e-ridesharing services in 2016. (e-ridesharing, in that context, implying real-time ride-hailing and carpooling services.)

Another report has it that as of 2017, Africa played host nearly 60 ride-sharing services across 21 countries. Key factors driving the demand for ride-hailing services in the region are rising urbanisation, growing youth population, increasing investments by several major players in ride-hailing services, and surging number of internet and smartphone users.

Moreover, ease of booking and enhanced passenger comfort offered by ride-hailing services are likely to further propel growth in the African ride-hailing segment for the foreseeable future. But e-hailing companies in Africa seem to be prime targets for witchhunts.

e-Hailing companies have it tough in Africa

Last November, SWVL, the bus-hailing startup that started in Egypt, was temporarily banned from Kenyan roads following an order by the National Transport and Safety Authority (NTSA). This was after the government institution claimed that the mass transit company was not duly licensed to operate in the country.

But it wasn’t just SWVL. This fight against what interest groups are calling a “ploy to put the traditional matatus out of business” tanked the bus-hailing unit of Little Cab known as Little Shuttle.

In a renewed fight, the NTSA wrote to the Police this year, asking them to impound SWVL vehicles for operating without proper licensing. This had something to do with SWVL’s choice of routes.

And it didn’t even end there, the NTSA had also requested that the Inspector-General of Police and the Director of Public Prosecutions arrest and prosecute SWVL’s CEO, Mostafa Kandil.

They also demanded that the startup be compelled to cease operations within Nairobi completely on grounds that SWVL has been operating illegally. While the dust appears to have settled since then, it is undeniable that the company is still walking a regulatory tightrope.

In Nigeria, bike-hailing startups saw their market evaporate right before their eyes after the government put an end to commercial motorcycling in key areas of Lagos State in February 2020.

These startups — which had invested heavily in equipment and onboarding riders having raised significant funding from mostly international investors — had been tussling with the government for months over licensing fees and disputed levies. And they got blindsided when the government basically decided to pull the plug altogether.

For cab-hailing platforms like Uber and Bolt, run-ins with Nigerian authorities have become commonplace, as has been the case for those platforms in South Africa. Similarly, both Careem and Uber have had their problems with the authorities in Egypt; problems dating as far back before the two platforms became one.

But as the ongoing global pandemic continues to shift paradigms, e-hailing may have finally caught a break in Africa. For what seems like the first time, an African country is actively proposing a regulation that is as close to “pro-e-hailing” as it gets.

Uganda to the rescue?

Just a couple of days ago, Uganda’s Ministry of Kampala Capital City Authority Affairs (KCCA), proposed new regulations for boda-boda (commercial motorcycles) and taxi operations in the nation’s capital city. These new regulations are to form part of the country’s economic plans after its COVID-19-enforced lockdown is lifted.

According to the Daily Monitor, Kampala’s Lord Mayor, Erias Lukwago, quoting the Ministry’s guidelines, stated that all boda-bodas shall operate under digital companies with the use of apps like SafeBoda, Uber, and Bolt.

“In the detail, after the lockdown, boda-bodas will continue operating by carrying cargo only and abiding by the curfew time, as they formalise their membership with registered digital companies like SafeBoda, Uber, and Bolt, among others, in the next 21 days,” Lukwago said.

According to the Mayor, once the lockdown is lifted, taxis will remain banned for 28 days. After payment of mandatory KCCA fees, the first 42 days will be used to obtain a route chart and allocated stages from the Transport Licencing Board at the end of a verification process.

After 42 days, only taxis registered under e-hailing platforms will be allowed to operate within the city, albeit under very strict conditions.

Although the newly-proposed regulations are still a long way off from implementation, it does signal a rare shift in fortune; one that favours e-hailing startups, which until now, have typically gotten the stick whenever government sought to act.

What to expect

Although reliable data is hard to come by, reports suggest that there may be over a million boda-bodas in Uganda with some 200,000 of those in the capital, Kampala. Like most cities undergoing uneven urbanisation, the transport sector remains largely informal — full of unregulated and unregistered workers.

The likes of SafeBoda, Bolt, Uber, InDriver, and Dial Jack are attempting to formalise the sector via their offer of e-hailing services. These platforms require up-to-date vehicle papers, licenses, and rigorous training on tech and safety for drivers.

With the coronavirus pandemic forcing governments to prescribe movement restrictions and adopt contact tracing measures, it appears Ugandan authorities now want to organise and regulate the transport sector so as to keep track of safety and monitor security issues more closely. And e-hailing companies seem like the best bet.

Although nothing is set in stone as of yet, e-hailing companies in Uganda can look forward to substantially increased patronage on their various platforms; a scenario that could spell intense competition in the local ride-hailing scene.

As a bonus point, Uganda could see smartphone and internet penetration go up in spite of the “Social Media Tax” imposed by long-standing President, Yoweri Museveni, in 2018.

Ugandans currently pay an over-the-top (OTT) tax of UGS 200.00 (USD 0.051) daily to access email and social media platforms. According to one report, an estimated 5 million Ugandans lost access to the internet thanks to the OTT.

As of July 2018, GSMA put smartphone adoption in Uganda at 16 percent, much lower than the sub-Saharan African average of 36 percent. Another report has it that up to 42 percent of Ugandans (19 million of the country’s 44.5 million inhabitants) are connected to the internet currently.

Those numbers can be expected to go up, along with financial inclusion since e-hailing encourages digital payments. As a matter of fact, mobile money is already quite popular in Uganda.

In 2018, a report claimed that only one in six Ugandans have bank accounts. In the East African country, payments are mainly done either in cash or via mobile money platforms like Airtel Money, MoMo Pay, and M-Pesa.

Indeed, the percentage of financially-excluded persons in Uganda stood at 15 percent in 2017 and that figure is expected to drop to 5 percent by 2022 largely due to the penetration of mobile money services.

Featured Image Courtesy: BBC