In Kenya, Pandemic-Related Financial Distress Puts SMEs In A Difficult Place

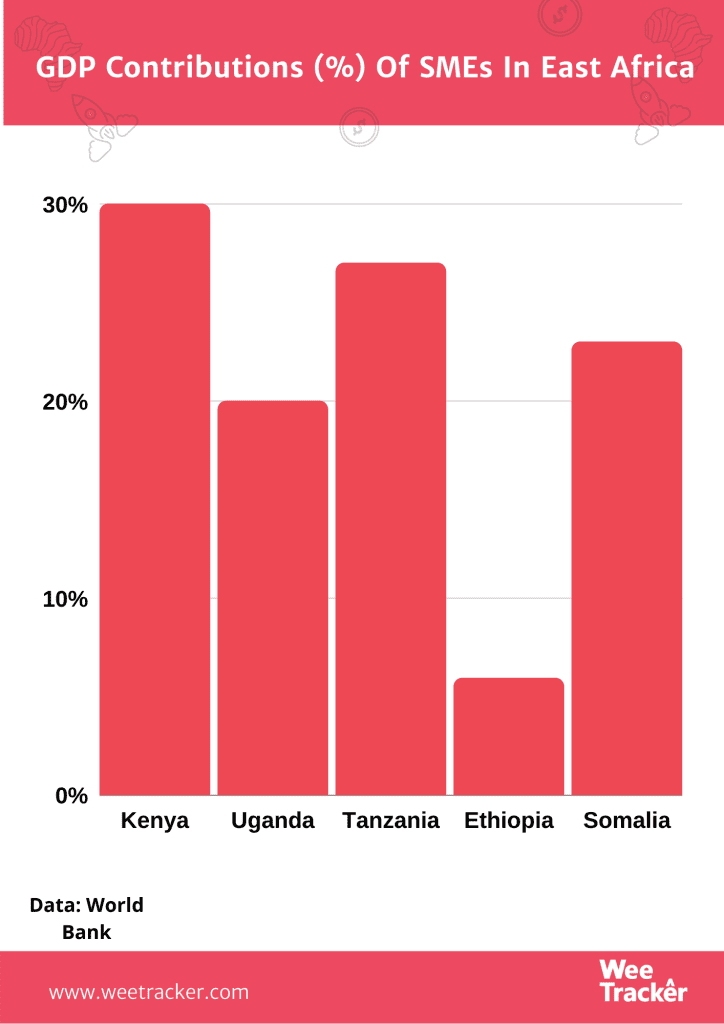

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) constitute 98 percent of all businesses in Kenya, creating 30 percent of jobs annually and contributing 30 percent to the East African nation’s economy.

A long-standing problem with most of such businesses, even in Africa as a whole, is the lack of access to finance and credit—particularly from financial institutions like commercial banks. However, right now, the challenges of the Kenyan arm of the industry are proving too much to handle.

Kenyan SMEs In A Fix

Per a study conducted by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), a good number of small businesses in the country struggle with lack of credit buffers and other resources needed to survive the effects of the novel coronavirus outbreak.

CBK Governor, Patrick Njoroge, referencing an April McKinsey survey, asserted that a majority of businesses will not make it through the crisis. 52 percent of the respondents in the survey are not sure whether there would be an economic recovery in Kenya. 16 percent, on the other hand, were sure that things won’t turn around for good.

The highlight of McKinsey’s survey is that 75 percent of Kenyan SMEs are of the opinion that the economy will be in a much worse situation by the end of June 2020. A meager 2 percent of people are hopeful for financial conditions to become better.

A larger portion of the research’s respondents expect the economic implications of the Covid-19 crisis to last for up to 2 years. Three quarters of SMEs are on the ropes and would be gone as they do not have any cash to keep the lights on, pay for supplies and compensate workers, Njoroge said. “The urgency to SMEs is clear to us and we understand it as we have a pulse on that part of the economy”.

Economic Translation

Job losses, reduced trade, deteriorating economy, and financial insecurity among others. Because SMEs are the breadwinners of Kenya’s business landscape, their inevitable financial distress means a devastating hit for the East African nation’s economy. More so, most of the large corporations are either disingerating or on the brink of total closure.

In the event where financial resources remain unprovided to save these small ventures, the economic challenges faced would add to the woes already cemented in by the pandemic. Kenya’s economy is projected to grow by just 1 percent this year (2020), down from 5.7 percent in 2019.

In Kenya, the operation of small businesses cuts across all economic sectors, sustaining a majority of the country’s households. There are about 7.41 million SMEs in the nation, although only 1.56 million are licensed. Apart from being one of the most prolific sources of employment, they create breeding ground for businesses to thrive.

SMEs are the lifeblood of the economy of developing countries, from which Kenya is not exempted. Their share of employment and wealth creation in such countries tend to be much more substantial than that of larger companies.

Loans In No Good Place Either

Private banks are left with the one choice of requesting higher interest rates from borrowers, because these institutions’ other sources of income have been dried up or frozen by the pandemic. That means, the less the SMEs, the littler the demand for loans, which actually justifies high interest rates.

Local banks in Kenya expect a drop in new loans as a result of the pandemic’s impact on the sector. A survey by the Kenya Bankers Association (KBA) shows that 94 percent of considered banks have experienced the drastic impact of the global health emergency.

Due to this, the financial institutions in the country expect to not be keen on taking new risks. Rather, the banks would want to focus on their existing credit portfolios in order to manage the prevailing risks.

As directed by the CBK, terms of loans have been restructured in Kenya in order to help customers mitigate the business effects of the outbreak. Kenya’s biggest bank by assets, KCB Group, for instance, has restructured over USD 1 Bn of its loans to customers. And, up to a quarter of its book could be affected by mid-June, its CEO, Joshua Oigara, said.

Also, the ratio of overdue loans in Kenya’s digital lending industry increased from 18 percent in March to 23 percent in April. Turnover fell by about a third as the impact of the coronavirus pandemic began hitting the East African nation.

All these put together puts the SME landscape in Kenya at risk of tipping over. If loans are unavailable, businesses would not just be able to remain in operation, but new ones won’t be able to enter the threshold.

A Panacea

The CBK has expressed calm in growing loan defaults even as commercial banks come under pressure from increased consumer risks. There are policies in place, which if used correctly, would arrest the evolution of (non-performing loans) NPLs, said Njoroge.

“These are highly exceptional times and it’s not the individual borrower credit risk that has changed. Banks shouldn’t be penalizing themselves for the risk neither should they penalize borrowers,” he added.

Meanwhile, the government has set up a credit scheme, through which Kenyan SMEs will get guarantees for loans. Business as usual is no longer an option.

The country’s Treasury is on the lookout for the approval of the Parliament for USD 30 Mn in seed capital for the scheme to commence. The European Union has committed USD 11 Mn to the cause.

Photo: Jessica Pamp Via Unsplash.