The Airtel-Telkom Merger Has Been Called Off—But Not Abruptly

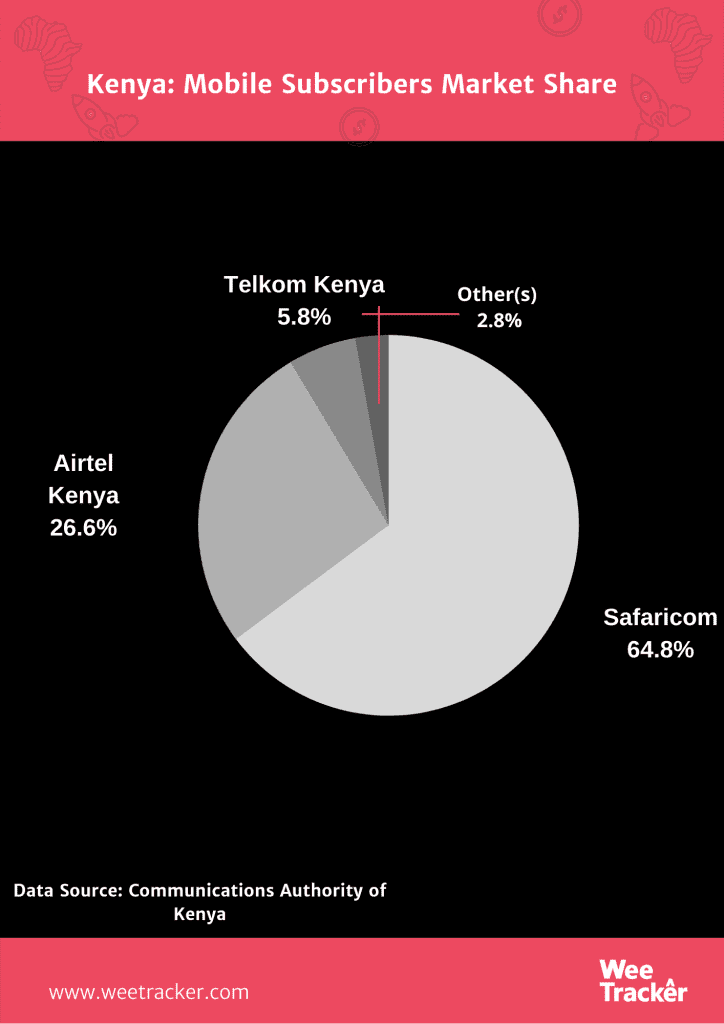

As promising as it seemed for the Kenyan telecommunications sector, the merger between Airtel Africa and Telkom Kenya has fallen through. Both parties have walked away from a deal, one which was supposed to metamorphose into a telco the right size to go against Safaricom, the most profitable company in East Africa.

Both operators entered an agreement to combine their Kenyan businesses in a bid to create an integrated telecommunications platform with mobile, enterprise and wholesale divisions. The transaction coming to an end means both firms will remain competitors in a market where majorly 3 operate.

Regulatory Hiccups?

Airtel And Telkom Kenya appeared to have had strong endeavors to reach a successful merger. But the transaction, having been in the works for more than a year, has gone through a rather lengthy process. In a statement by Airtel Africa, both telcos have as a result of the inclusive regulatory hiccups decided to no longer pursue the completion.

It is not new for regulatory hiccups to stall African mergers. However, apparently, the longer it takes, the more complicated it becomes. At least, there is contextually little to learn from the less-strangled ride-hailing deal between Uber and Careem in the Middle East. Airtel and Telkom Kenya parting ways is a sign that regulations could be a major stumbling block.

Nevertheless, the telecoms providers seem to not be divulging much regarding the nail on the coffin of their business transfer. Since February 2019 when it kicked off, both parties have not really been vocal about what was to be once the deal is completed. Little wonder why they’re keeping most of the major reasons within four walls, for now.

While Airtel Africa is an offshoot of India’s Bharti Airtel and with a larger coverage, Telkom Kenya happens to be the telco with the least market share among the 3 major players in the Kenyan telecoms landscape. It is 60 percent owned by private equity firm Helios and 40 percent owned by the Kenyan government.

Safaricom accounts for 8.93 billion minutes in the local voice market, while Airtel and Telkom have 4.78 billion minutes and 619 million minutes, respectively. A merger was theoretically supposed to enable both have 5.6 billion minutes, to close in on their competitor’s numbers. As at 31st March 2020, the number of active mobile subscriptions (SIM1 Cards) in the country

stood at 55.2 million.

But Not Abruptly

When word first got out that the Communication Authority of Kenya (CAK) had suspended the planned merger between Airtel and Telkom Kenya, it was vivid that stretch of hurdles would only get longer.

At the time, CAK was investigating whether public funds were lost when the cabinet green-lighted the restructuring exercise that enabled Orange SA acquire a 51 percent stake in Telkom Kenya.

Because of the deal, Mobicom, Telkom Kenya’s largest dealer, had to furlough over 800 employees, having experienced a drop in business. On its part, Telkom was reportedly severing ties with 575 workers on account of redundancy, in order to enable the merger see the light of day.

The deal was approved by the CAK, but it hit a snag when it came to the National Treasury’s turn to make things proceed.

In July, 2020, it was revealed that the deal was scheduled for completion in December 2019. According to the CAK, the stall came from the office of the National Treasury, which is needed to sign off all the government-backed transactions of this type.

That was pretty much the last development heard of the merger, before the deal was completely taken off the tables by the parties. These delays did not just compromise the already shrinking market share of Telkom Kenya, but also slowed down the telco’s new investments.

Who Else Had A Hand?

In February 2020, both telcos joined hands to protest the CAK’s conditions for the transaction. One on part, the watchdog mandated that the companies should not sell any assets of the resultant entity within the first five years.

On another hand, it said the resulting Airtel-Telkom marriage should not sell the four frequency spectrum licences and five operating licences including a submarine cable landing licence, while retaining its staff for 2 years.

In their protests, Airtel and Telkom sought the freedom to engage in sales within their own time limits, as well as cut the employee size to the best fit for them.

Meanwhile, Safaricom, in December 2019, debunked circulations that it was opposing the Airtel-Telkom Merger. Nevertheless, it demanded the KES 1.2 Bn (USD 11,108,710) owed by both operators be paid before the amalgamation would happen. Safaricom also cited the need for rebalancing in frequencies allocation, but only post-merger.

There’s no telling how a compendium of these bottlenecks formed a major hamstring for the union of Airtel and Telkom Kenya, but there may be much to discover why the companies called it quits after so much time.

Featured Image: Aljazeera