The Pandemic Has Moved 3D Printing From Fiction To Fact In Africa

In one expectedly hilarious episode of Chuck Lorre and Bill Prady’s hit comedy series, The Big Bang Theory, two of the characters, Howard Wolowitz and Rajesh Koothrappali, basically blew five grand on a pair of ridiculous miniature plastic dolls. Or maybe it was three dolls. Either way, five thousand bucks was spent.

Actually, the backstory is that Wolowitz and Koothrapali — both nerds who loved comic books and action figures despite being among top scholars at Caltech — were bummed after they received the finished product from an online shop that claimed to fabricate and deliver action figures that could look like anyone.

The two science geeks had ordered two miniature action figures made in their image, but they received two grotesque figurines. Disappointed, they opted to fix the problem by purchasing a 3D printer for five thousand dollars; for the sole purpose of printing and gifting themselves a couple of dolls that cost less than fifty bucks. And they succeeded.

The anecdote laid out in the preceding paragraphs does primarily convey ridiculousness and mirth. But there’s a secondary subtle message that is alluded to; the under-acknowledged relevance of 3D printing (AKA additive manufacturing); which fundamentally translates to the manufacture of physical items from a 3-dimensional digital model.

3D Printing: An unlikely saviour amid crisis?

It is often thought of as the stuff of movies; something very close to science fiction. Seeing a tool, a toy, a prosthetic limb or a spare part for a machine take form by itself after injecting heated metal or plastic into the nozzle of some machine is no doubt a wondrous sight, even borderline magical. But that’s pretty much how 3D printing works.

Although it now has important applications in today’s world, some 40 years after it first popped up, 3D printing is still generally regarded as “cool” — something that is fascinating and great to have, but not a big deal just yet. A technology that thankfully exists, but is not that relevant. Yet.

However, a global catastrophe that has rocked the world since the start of the year may have provided a rare opportunity for 3D printing to audition (at the most crucial of times) and shift the perception.

And boy, did it deliver! All over the world, 3D printing went from sci-fi movie prop to real-world lifesaver overnight, during a critical stage of the pandemic.

“I think globally 3D printing has come into the limelight because of its ability to be a first responder in terms of manufacturing,” said Mehul Shah, founder and CEO of Nairobi-based 3D printing company, Ultra Red Technologies.

“The agility and speed at which you can create products are what is a standout feature and I think that because the world was not ready for this pandemic, 3D printing was a great source of quick fixes and very fast protection measures.”

Shah added, “The examples of this were the adaptations of scuba masks to ventilator masks and respirators using 3D printed attachments. Another major example is the rapid design and production of face shields, which have been serving so many front line workers from the earliest days of this pandemic.”

As the rapid spread of the novel coronavirus forced movement restrictions that disrupted global supply chains, hospitals became overburdened and medical equipment shortages became a huge concern, more so in parts of the developing world where fragile healthcare systems are heavily dependent on imports and donors.

But as necessity is often the mother of invention, those shortcomings set the stage for 3D printing to come to the fore globally. In Africa, especially, where the annual healthcare financing gap is currently USD 66 Bn-wide, according to UNECA, the ‘still-very-niche’ technology-assisted.

“Given the pandemic, 3D printing has come to the aid of many medical institutions, professional services and private individuals who know someone or institutions with access to 3D printers,” enthused Isak Van der Walt, Manager of Digital Scholarship & Innovation, at the University Of Pretoria, South Africa.

Van der Walt oversaw a quick deployment of the technology in the rapid production of visor frames for face shields and other useful items right within the walls of the institution.

When science fiction becomes a real-life fix

Science fiction is fast becoming science fact, and none more so than 3D printing, which went from only being recognised on the sidelines — as a nascent production method for odd fittings and special aircraft components — to saving lives in the middle of a devastating pandemic.

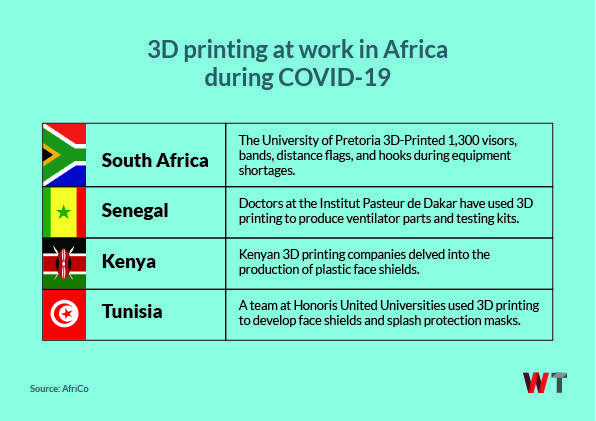

In Senegal, doctors at the Institut Pasteur de Dakar used 3D printing to produce ventilator parts and increase SARS-CoV-2 testing in such a way that they claim has reduced costs substantially. The earlier mentioned Ultra Red, together with other Kenyan 3D printing companies, delved into the production of plastic face shields.

As was earlier alluded, the University of Pretoria used its cutting edge 3D printing technology to manufacture visors, after healthcare workers reported equipment shortages while tackling the coronavirus pandemic. But that was just for starters.

“In addition to the visors, we also printed hooks that help people open doors without actually touching it. We also printed cones that help us create social distancing queues and they are more flexible and movable than stickers,” said Van der Walt.

The team also produced bands and distance flags. To date, the university department claims it has 3D-printed over 1,300 items that are known to foil the spread of the virus.

Furthermore, in response to the health crisis, a team of scientists, doctors, engineers, students, and professionals from Honoris United Universities, Tunisia, developed a prototype for a novel non-invasive respirator. The team also developed face shields and splash protection masks, which can be affordably and quickly manufactured via 3D printing.

All these are prime examples of how the African 3D printing community stepped up to the challenge served up by what could be described as an unprecedented health emergency.

“The creation of new equipment, features, fittings, etc. shifts the focus from a dependence on the international supply chain to a local supply chain, shortening lead times and often providing cost-effective alternatives,” Van der Walt explained.

Interestingly, even luxury automakers like Bentley and Rolls Royce 3D printed face shields. It was pleasantly surprising that a technology that has hitherto been regarded as exotic and mostly experimental at best could play such an important role on such short notice — at a time when the world was reeling. Needless to say, the technology was anything but part of daily lingo before now.

What did 3D printing look like in pre-COVID Africa?

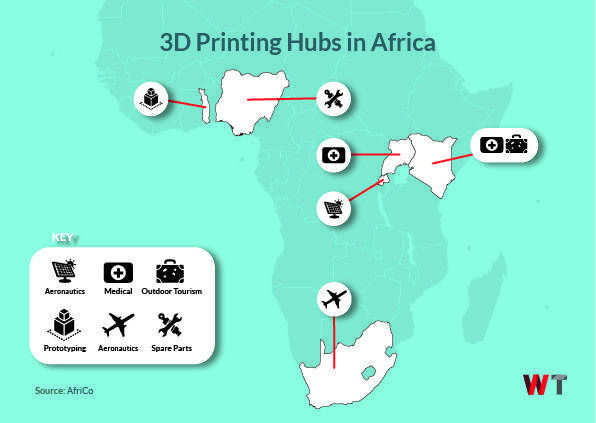

As per data from AfriCO, a venture and financial database for African private companies, a total of 58 companies are involved in the business of 3D printing across the African continent, as of March 2020. At least 43 of these companies were founded in or after 2014.

When it comes to 3D printing in Africa, South Africa leads the way, growing its 3D printing machines from 268 in 2011 to 3,500 by the end of 2015. Before COVID-19 happened, 3D printing in South Africa mostly hovered around prototyping and research work.

South Africa announced the Aeroswift project in 2017. The project saw a South African-built titanium powder 3D printer successfully produce aircraft parts, including a throttle lever, a condition lever grip, and a fuel tank pylon bracket, with the first commercial applications earmarked for 2019.

Beyond South Africa, Kenya also has a vibrant 3D printing community, with interests revolving around — but not limited to — health applications. Companies like Ultra Red, Kijenzi, Objet Kenya, Kenya’s Fab Lab, are active in the space.

Elsewhere in Africa, the 3D printing scene pre-COVID was tepid but not comatose. In Lagos, Nigeria, ElePhab works to provide replacement parts for Nigerian industries using 3D printing. In Uganda, the Comprehensive Rehabilitation Services hospital uses 3D printing to more efficiently create prosthetic limbs for amputees.

In addition, Togo’s capital, Lome, hosts a 3D printer made from electronic waste which has been used to build product prototypes for local entrepreneurs, including anti-theft products for motorcycles. Another example is found in Rwanda where Great Lakes Energy 3D prints packaging and storage solutions for its solar products.

Outside of Africa, the technology has found use in rocket parts, aerospace, life sciences and healthcare, as well as the construction of buildings. In fact, popular brands like Adidas and Nike are producing 3D-printed footwear at the moment.

Did 3D printing pass the pandemic edition of the audition?

By definition, 3D printing is a programmed additive process that creates finished products by adding material layer by layer, much like how a painter might work on a surface. The materials added are shaped into designs to fulfill specific functions.

As Shah told us, “3D printing is a tool that has more flexibility than any other form of manufacturing.”

Indeed, among the many advantages which 3D printing has over traditional manufacturing processes is the ability to quickly create highly customized or differentiated products in small batches.

That kind of flexibility allows for quick and easy repurposing of production lines. It’s why automakers were able to switch from making, say windshields or car engine parts, to mass-producing visors almost instantly, in the middle of the pandemic.

These 3D printing advantages were put to use amid the crisis, and stakeholders believe they make for a winning combination.

Emeka Okoye, Founder and CEO of Cymantiks, reckons that while most of the 3D printing efforts recorded turned out to be “experimental” in these parts, it was a good sign nonetheless.

“It showed potential on how it could be positioned for near future usage via a phenomenon called additive manufacturing which brings the benefits of producing small amounts of complex parts cheaply,“ he said.

But, don’t more machines mean more lost jobs?

By 2030, one out of four workers worldwide may be African, according to the global consulting firm, McKinsey & Company.

This implies that the global hub for labour-intensive manufacturing is expected to increasingly shift to low-to-middle income countries (LMCs) where labour costs are lower. But this is far from certain.

With the emergence of 3D printing, robotics, Internet of Things (IoT), and other technologies plugged into the so-called “4th industrial revolution” — and the increased adoption of those technologies in China, Europe, and the United States — low labour costs may not matter much in the long term in determining where jobs go, given the potential reshuffling of global value chains.

The preceding paragraph is just a lot of big words that basically draw attention to the notion that the “technology quake” that is upon us may take away a lot of jobs, as it would mean fewer entry points for African economies into global value chains.

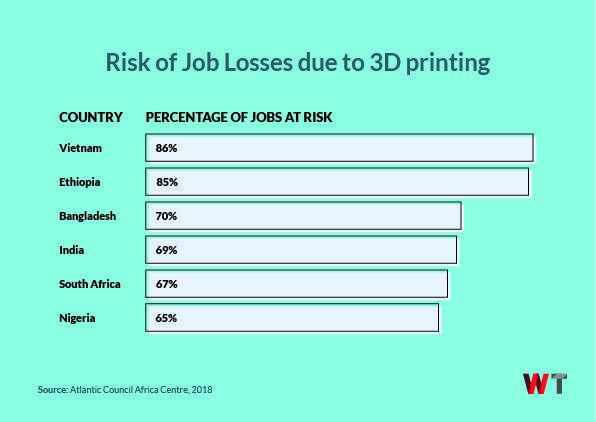

Indeed, a publication by Aleksandra Gadzala, Head of Research at Singularity Group, suggests that 85 percent of Ethiopian jobs are at risk of being replaced by 3D printing and automation. So is 67 percent of jobs in South Africa, and 65 percent of jobs in Nigeria.

In a continent where youths already account for up to 60 percent of its jobless according to the UN, such massive job cuts could set back industrialisation and multiply the tendency of social unrest as Africa’s youth population — an estimated 830 million individuals by 2050 — fight for scarce opportunities in the ever congested job market.

So, will 3D printing make jobs disappear? The most popular answer to that question is that the technology will create many more jobs than it will take.

“[It is] not true [that 3D printing will take jobs]. In fact, it will increase employment via the increase of small scale manufacturing that 3D printers will bring,” Okoye argued.

“If we are smart in Africa, then we should encourage 3D printers to be pervasive so that it will be in more hands to boost productivity and wealth creation. 3D printers should be made available in every secondary school, as well as higher educational institutions too,” he added.

For Shah, it is a given that jobs and industries will be impacted, but he reckons that many more high-skill jobs will materialise.

“3D printing and 3D design are both technically high-skill level jobs and they will require a new way of thinking. I think that 3D printing will actually have the potential to create far more jobs than it will replace,” he said.

“More micro-entrepreneurs will be able to get their products out and it will see people taking ownership and risks to grow the economy. The reliance on larger factories for employing many people will be less and to me, that is a good thing.”

He added. “With a few large companies employing the majority of the workforce, there is a major risk of many people losing jobs overnight. This pandemic has taught us that, and we should know now that creating the next generation of entrepreneurs and unlocking future technologies is how we survive in an ever-changing world.”

Those words are echoed by Van der Walt who is of the view that adaptation is key as 3D printing brings with it, its own new set of skills requirements and expertise which has the potential for job creation and/or job enrichment.

“I don’t see 3D printing as a threat, I think the key, as current and future employees, is to acknowledge the fact that technological advances will impact jobs and industries.

“In the early 80s, we used to have typing pools full of staff whose only job was to type, then came the personal computer and all those jobs were under threat…unless you were willing to adapt and change as an individual,” he reckons.

However, for what it’s worth, 3D printing technology is, at the moment, nowhere near bringing about the monumental change that it is often linked to in both utopian and dystopian accounts of what the future might look like.

At its core, 3D printing is still just another manufacturing process, one that is likely to supplement rather than replace traditional methods.

Based on the realities of today’s world, 3D printing is still underdeveloped and hard to scale. Even as the range of printable materials is expanding, it remains limited.

Generally, 3D printers are not great at handling soft, flexible materials, for instance, which is why it found its earliest adopters in the automotive and aerospace industries — both of which are big on tough but flexible materials.

Notwithstanding, stakeholders like Shah and Van der Walt envisage a future where it uplifts the local manufacturing sector.