Are African States Blocking Mobile/Internet Boom & Choking Network Operators?

Mobile penetration is growing faster in Sub-Saharan Africa than in any other region in the world.

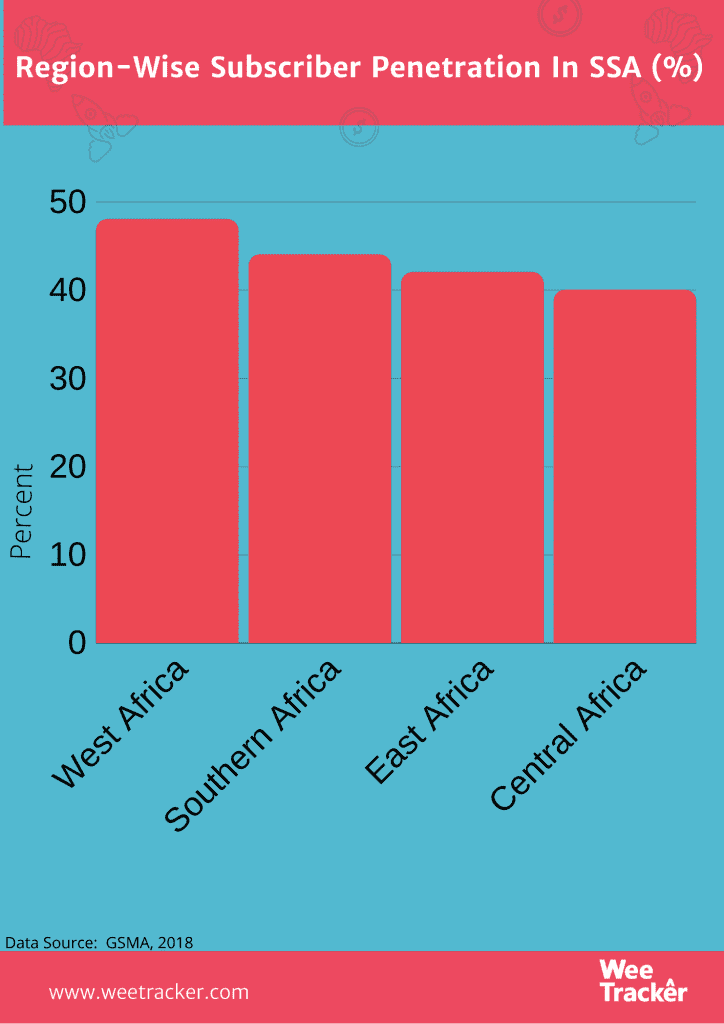

However, with a subscriber penetration rate of just 44 percent (456 million unique subscribers as of 2018), it still trails the global average of 66 percent by some margin.

More so, only around 239 million people (equivalent to 23 percent of the population), use mobile internet on a regular basis. Again, this is well behind the global average of 53.6 percent.

In its report titled: “The Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa 2019”, the GSMA predicts that Sub-Saharan Africa will remain the fastest-growing region and account for over 600 million subscribers by 2025.

But to get there, African states may want to also do their bit to address the current shortcomings and champion the course.

Being easy targets, Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) in Africa have often gotten the stick and taken the blame for inadequate and poor mobile network services.

But there’s more to it than meets the eye. Government regulators and policymakers may even be just as culpable (if not more) on the subject of limited network access and poor penetration in Africa.

Counterpoint: Telcos Probably Get Too Much Blame

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when one tries to call an old aunt in the Eastern hinterlands and can’t reach her? Bad telecoms network!

Where does one push their frustrations to when a page load or a download is taking forever? The service providers are the bad guys!

But here’s something that is often not given thought: Telcos can only do so much when the system is rigged to make their job of providing quality service across all areas as difficult as possible from the start.

Last week, a State in Southwestern Nigeria crashed Right of Way (RoW) charges by as much as 96 percent [from NGN 4.5 K (USD 11.52) to NGN 145.00 (USD 0.37) per metre], to improve broadband penetration.

The other States in Nigeria charge wildly differing rates, ranging from NGN 500.00 (USD 1.28) to NGN 5 K (USD 12.80) per linear meter.

This would imply that the cost of laying broadband fibre across a length of 1 kilometre in Nigeria’s Ekiti State is now only NGN 145 K (USD 371.60), instead of the previous NGN 4.5 Mn (USD 11.5 K).

Spot the huge difference? That’s just one instance of the many hurdles service providers have to first surmount — besides the actual cost of infrastructure and manpower — in the process of bringing mobile services to communities.

It’s akin to having to first pay a fortune to the authorities before one can install, on their own account, something that is very much needed.

The RoW Example

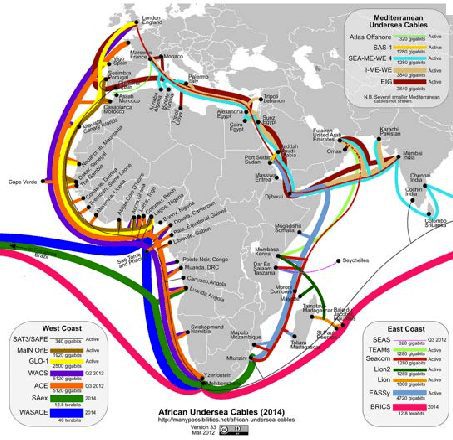

The graphic above is a common feature of discussions involving developments around broadband connectivity in Africa. It shows all the undersea cables bringing capacity to the West African coast.

Just last week, Facebook Inc. was reported to be planning a USD 1 Bn undersea cable for Africa. There’s no shortage of capacity.

The problem? Much of the installed capacity stays unused especially in low-density, low-income areas — especially rural areas. Why? It has something to do with the inadequacies in terrestrial infrastructure.

The result? In such rural areas, 2G connectivity could be all that one may get on a good day. Internet access is limited to slow WhatsApp texting. Some routine phone calls may not even go through.

While it’s possible to put this connection issue down to many things, one of the key reasons is the RoW taxes. Basically, if a service provider wanted to lay terrestrial fibre, they’d have to pay a tax to the government. It’s a legitimate source of revenue for the State.

However, in some States, the tax is so high that it could represent as much as 70 percent of the entire cost of laying the fibre.

So, the service companies typically prioritise, only choosing to go through the trouble if it’s worth it, or if it makes business sense. (They’re businesses with shareholders after all).

The companies only invest where it makes sense, no point laying expensive fibre in a low-density, low-income rural area where returns will be small due to low usage and patronage.

The result of this is that the neglected areas get poor or no service and lose all the potential benefits. The areas that do get the service may not get the best service because of the barriers to entry. And the service would typically cost more than it should.

Echoing that thought, an executive at Africa’s largest telco, MTN Group, which has operations in 20+ countries around the globe (including 18 African nations) told WeeTracker that RoW charges vary significantly across African countries and that it can be a stumbling block.

“Right of Way varies from country to country in Africa. The costs also vary significantly from one municipality to another within each country,” said Nompilo Morafo, Executive: Corporate Affairs for MTN Group.

“Based on our experience, RoW cost has been a hindrance to the rollout of fibre, in particular,” he added.

The MTN Group executive also said that RoW charges have had a bearing on urban centres more than rural areas because rural areas are typically avoided when it comes to laying fibre due to the associated costs.

“RoW has predominately impacted urban areas more than rural areas. Fibre is not commonly used within rural areas due to associated costs. RoW has impacted the rate at which fibre can be rolled out to sites and homes.”

Why so much emphasis on “fibre” anyway?

Well, that’s because fibre is used by many telecommunications companies and service providers to transmit telephone signals, internet communication, and even cable television signals.

Due to much lower attenuation and interference, fibre has large advantages over copper wire in long-distance, high-demand applications.

The cost of rolling out fibre to homes has become more cost-effective since the turn of the millennium, but it’s not cheap. Prices have dropped to USD 850.00 per subscriber in the U.S. and lower in countries like The Netherlands, where digging costs are low and housing density is high.

Data on RoW charges across Africa is not readily available but as Morafo of MTN Group told WeeTracker, it varies significantly from country to country, and in none of those countries is it particularly cheap.

But it goes deeper than laying fibre

In a December 2019 interview with THISDAY’s Emma Okonji, Funke Opeke, the CEO of MainOne; a service provider of internet, voice, data centre and cloud, spoke thus:

“It has become increasingly difficult to deploy infrastructure because there is a belief that every telecom company is a cash cow and companies must pay various government agencies and even communities numerous fees for Rights of Way (RoW) and Base Station installation to play.”

She added:

“These developments deprive our citizens, especially our youth and less-privileged access to services, which could help them achieve better financial outcomes.”

Take Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria, for instance; telcos are typically fronted with multiple overlapping taxes and levies that vary between several government agencies, communities, and tax authorities. There are up to half a dozen of such payable taxes with foggy interpretations.

Service providers in Africa are typically considered as companies with infinitely-deep pockets (and they probably are — operator revenue hit USD 42 Bn in 2018). And the authorities like to collect.

The taxation of mobile services remains a significant policy issue. Across a sample of 19 countries studied in a GSMA report from 2014, over USD 3.00 in every USD 10.00 of mobile revenue was transferred to the government in the form of taxes, regulatory fees or other charges.

The net effect is that broadband penetration is limited to only areas where the bulgy expense makes economic sense. And even in those areas, service costs more than it should and the connection may be spotty because funds that could have supported the actual work are used to “convince” the authorities to allow the actual work to proceed.

Hence, a diluted offering in general because of financial adjustments, since businesses have to also make money. MNOs in Africa can certainly do better, but so should the authorities.

Is there a way forward?

Once again, let’s consider Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria, which, by itself, accounts for one-third of the revenue of Africa’s largest telco, MTN Group.

Even though mobile teledensity in Nigeria is close to 95 percent, broadband penetration still hovers around 35 percent.

A critical analysis shows that the majority of the broadband infrastructure in the country is concentrated in urban areas with a glut of submarine cable infrastructure on its shores, and overlapping terrestrial fibre networks in its largest cities. These structures interconnect those cities while secondary cities, towns, and rural areas are poorly connected.

The above holds true for many African countries. While over the past two decades, the continent has benefited from investments in telecoms which has lifted teledensity, those investments have slowed over the past few years. Also, comparative progress has stalled relative to other regions across the globe where broadband adoption has since exploded.

As Opeke explained in the earlier-mentioned interview, in order to achieve better broadband penetration, infrastructure coverage that does not leave out the most vulnerable citizens is needed.

“The economics, therefore, dictates that such infrastructure be deployed as shared infrastructure and that the fees and taxes to deploy the infrastructure cannot be prohibitive for financial viability,” she said.

“Advanced economies with much higher GDP per capita impose regulation to ensure telecoms infrastructure is shared, and we need to do the same. Shared infrastructure will reduce costs to the operators and translate to price reductions to the consumer.”

Given the current economic environment, it is not for the government to fund the infrastructure, but it is for the government to reduce the barriers and ensure that permits are granted quickly and at low cost (cue the Ekiti State example).

This is especially important at a time like this when the coronavirus pandemic and the consequent restrictions have necessitated the expansion of telecommunications networks worldwide.

In the quest for cheaper and better broadband services in Africa — bearing in mind that Africans pay more for such services than people in other regions — the government authorities, just like the service providers, have an important role to play.

Featured Image Courtesy: WiredUK